8 June 1896 When Cinema Came to Bristol (Part 1) Mark Fuller

Share this

May/June 1896 must have seemed such an exciting time to the citizens of late-Victorian Britain.

Industry was prospering, the rights and conditions of workers were slowly improving, thanks to increasing unionisation, and were already far better than those endured a generation earlier. There was leisure time, most people had some money with which to enjoy it, and peace, relatively (there was the usual fighting associated with the business of Empire, but no full-scale wars). Meanwhile, in the entertainment sector a revolution was occurring . . . though one that was largely overlooked.

Even avid readers of The Era, the weekly show-business broadsheet, covering the whole spectrum from high opera to end-of-pier sideshows, would be hard pressed to spot anything untoward in their world. It was business as normal; in fact, better than normal. At the upper end, the impresario Sir Augustus Harris had single-handedly revived opera in London, from the times when members of the chorus would proffer their hats for coinage as the curtain fell, to a level where we could look at productions in Paris, Bayreuth, and Italy and not feel too embarrassed. We now had Covent Garden Opera House, and Harris productions toured to the great halls in all the major cities. D’Oyly Carte had five separate companies, four permanently touring.

The global theatrical hit was the play Trilby, with its villain Svengali. Sir Henry Irving had just returned from a sensational eight-month tour of the United States. The music halls were at, or were reaching, their peak. Artistes whose names are still famous today were touring the People’s Palaces and the Empires to crowds of thousands a night, earning fortunes for themselves and the hall owners, and in demand not just here but in all the major cities in the British Empire, and in the United States.

But show-business also had a Wild-West feel about it; copyright was enforced, as was censorship from the office of the Lord Chamberlain, but it was obviously hard to keep on top of. No issue of The Era is complete without multiple advertisements staking claims to rights ownership, from plays (there seemed to be many unauthorised productions of Trilby doing the rounds, as well as parody burlesque versions) to popular songs, and patents for stage-relevant inventions. Court reports of patent or rights infringements cases would follow. It was into this arena, and febrile atmosphere, that the new invention, the film projector, was just emerging.

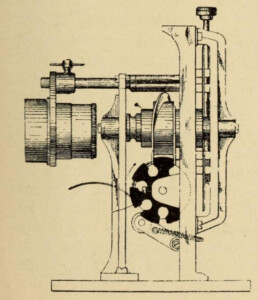

Not that anyone was calling it that. The new device had many names depending on where it was, or whose design was being used. From Paris came imports of the Lumière Freres’ Cinematographe. Their main competitor was Robert William Paul, based in North London, with his Animatographe (or occasionally Animatograph) exclusively based at the Alhambra, and his Theatrograph for other contexts. There was a slew of others: Fred Harvard’s Animatoscope, and/or Cinematoscope; Mr Jones of Enkel-street’s Cinemotoscope; Moore and Burgess’ Vitagraphe; Mr Trench in Reading’s Kinetograph. Meanwhile, Thomas Edison was rather late to the party, with his Vitascope seemingly only being seen at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York. With the exception of Edison, Paul and the Lumières, the passage of time has obscured whether these others were using rebadged machines, or counterfeits, or machines of their own devising.

Thus it was that legitimate inventor/ businessman Paul was using some of his advertising spend, and influence, in The Era of June 13 1896:

‘To warn provincial [Music Hall] managers against the spurious machines and inferior pictures which are being offered by various individuals under the assumed name of The Animatographe. There is only one Animatographe in existence, and that is in use at The Alhambra. No-one else has the right or the means to reproduce the pictures taken specially for the machine by the inventor, Mr Paul, of 44 Hatton-garden, London.’

This appeared in the regular column Music Hall Gossip, but the Alhambra’s advertisement also carried the same injunction, as did Paul’s own advertisement, all in the same edition. Similar but more muted warnings had been included in his own advertisement before, but it seems that his patience was wearing thin.

There may have been an element of concern, too, for Paul. He had dominated the showing of moving pictures in the UK; by which I mean London. As well as his flagship location of the Alhambra, he had his Theatrograph as part of David Devant’s and Nevil Maskelyne’s peerless magic show at the Egyptian Hall, as well as engagements at Olympia, the Britannia, Hoxton, and the Canterbury music halls in London. The Lumières’ Cinematographe was being shown by Monsieur Felicien Trewey at the Empire Theatre, London, and was about to embark on a tour of the provincial Empires: the brand new 2,000-seat Cardiff Empire, the Edinburgh Empire Palace, and the Empire, Sheffield would follow later in June.

The exhibition of moving pictures was spreading, almost virally, from the premium London halls, to the not-quite-top London halls, and into the major music halls in the larger cities of the provinces. Various dealers in projection machinery were starting up: Mr B Doyle of Belgravia, Fred Harvard of Kennington Road, Tom Shaw of The Strand, Mr Jones of Holloway, Fred Duval . . . Anyone with about £60 could buy the equipment and enough films to become a music hall turn, and that equipment could also have done extra duty as a film camera and developing apparatus. Paul may have felt that he wasn’t getting his full slice of the cake. If, as Edison’s Kinetoscope had recently proved to be, projected moving pictures turned out to be a short-lived affair, superseded quickly by something superior, there was no time to waste. If Paul had felt concern, it was not without business logic behind it, hence those admonitions in The Era. He wanted that expanding business for his firm, while the going was good, and he may already have been thinking about a stock market flotation, which would indeed happen the following year.

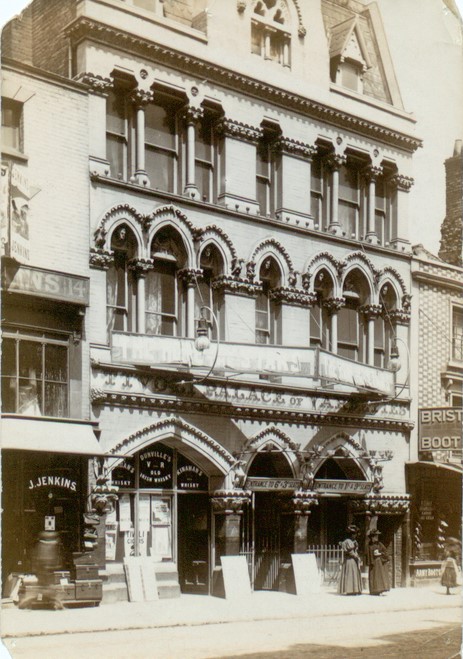

That very week, starting on Monday 8 June, moving pictures appeared on a public screen in Bristol for the first time. But the Tivoli, Broadmead, under Manager Mr E Leon, was not one of the major music halls. At least, not any more. It had been, when it had been built as the Alhambra, in 1870. But the gentrification of music hall in late-Victorian Britain had brought increased competition to the older halls, with bigger, grander, newer halls. The Alhambra, rechristened the Star in 1889, found itself up against the 3,000-seat People’s Palace in Baldwin Street, opening in 1892 (now just a facade for student apartments) and the Empire Palace of Varieties, Old Market, opening in 1893 (demolished for road improvements in the ’60s). Both were parts of national chains, Livermore Brothers’ and Moss & Thornton’s respectively, which gave them far greater power and financial clout in the booking of touring star artistes. The writing was on the wall.

If the Star was going to go under, though, it would not do so without a fight. It was bought, refurbished and reopened as the New Tivoli by Mr Leon in July 1895; but the old inherent problems remained. It was smaller than the other two halls and while its alcohol license was a revenue stream they did not have, it lent the place a less refined air. Even the Empire was struggling. At this point in time, there was only room for two halls in Bristol. Fortunately for the New Tivoli, the Empire was closed. This was not uncommon practice in those days, a summer break allowing for maintenance and refurbishment works, while crowds thinned with the competition of more fresh-air pursuits than entertainments in hot and smoky halls. This time, though, the Empire was in the hands of the Official Receivers, who, in August would put it, together with its twinned neighbour the Woolpack Inn, up for auction. Bidding reached £16,000, but the lot was withdrawn as it had failed to meet its reserve.

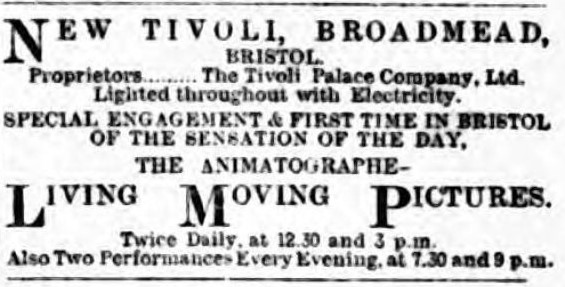

So Mr Leon strikes; and on that Monday 8 June 1896, advertisements appear in the local press: The Bristol Mercury, The Bristol Times and Mirror, and The Western Daily Press.

It’s a brave move. Not only is Mr Leon going forward with a new technology, but he is clearing the decks at his hall to showcase it; four shows per day over this first week, and not, as was the London practice, as a turn in a variety show, or as a support to a performance, but the sole advertised attraction, a repeating show that cannot have been much more than an hour long, if the advertised show times in the evening are accurate.

The wording of the advertisement is also quite subtle. It echoes, but does not quite copy, those for R W Paul’s shows in London. The Animatographe is the name of Paul’s Alhambra-based machine; he advertised his shows as Living Moving Photographs. So, who is the person behind these shows? Is it Paul himself, or one of his many London competitors, with a bought-in or counterfeited machine, either of his or Messrs Lumières’ design? Well, the surprising answer is . . . None Of The Above.

The two reviews we currently have of this first show are both quite glorious in their own way. The slightly higher-brow Bristol Mercury‘s correspondent reacted with a somewhat ill-disguised distaste at the whole affair. It’s described as

‘an elaborate Kinetoscope and Magic Lantern in one, and is accredited with as many inventions as Homer was with birthplaces. Its object is to throw life-like moving pictures on its screen. The fascination that representations of the real, rather than the real itself, have over us is remarkable. We pay our pence to see in a Camera Obscura the very view that we could see outside for nothing. It is in this curious predilection of the amusement-loving public that the popularity of The Animatographe will exist, though the pictures may sometimes prove hardly so good or satisfactory as the originals.’

Tragically, we do not know the identity of the writer of this, for remarkably he or she has critiqued all of cinema history at first viewing. Further on, the writer ponders whether the ‘amusement caused by . . . the exaggerated stalk of a tragedian, can be attributed to the faithful camera catching what escapes the eye of an ordinary observer’.

So that’s the history of screen versus theatre acting dealt with, too. There was less approval for the meatier subjects screened: ‘Gruesome and grim beyond measure are the representations of “The Execution of Mary Stuart” [sic] and “The Burning of Joan Of Arc”, given in a most realistic and ghastly fashion.’

The review from The Bristol Times and Mirror has in precise detail what it lacks in prophecy; and it’s thanks to this reviewer that we can identify the man behind the show, if not the name of the apparatus, ‘of his own devising’. The showman is the otherwise unsuspected Augustus Rosenberg of Newcastle. We are given a very full picture of the event. Again, there is a reference to the Kinetoscope. It is possible that some of the audience had seen the Edison money-in-the-slot predecessor to projected film. There had been a short-lived Kinetoscope Parlour or exhibition in Park Street in the early months of 1895, and they had turned up as amusements at other venues in Bristol since; for instance, at an event to finally finish the fundraising drive for a statue of Edward Colston to be erected in the city centre.

There was music. The Tivoli had its own band, under the direction of Charles E Howell, to entertain before and after the films. Mr Howell himself gave a piano solo during the brief interval. During the two dance films that finished each half, there was a musical accompaniment, a violin solo from the Tivoli band’s principal violinist, Leon A Bassett. Up until April, he had been the musical director of the Empire. While Mr Rosenberg himself spoke at the event, describing the apparatus, the films themselves were described and delineated by Mr Walter Lynn Jr, billed as being Mr Rosenberg’s manager, but also a conjuror and sleight-of-hand artist in his own right.

The film programme consisted of, in our reviewer’s words: ‘In The Dentist’s Chair; The Village Blacksmith; A Wrestling Match Between a Dog and his Master; A Burlesque Boxing Match; Three Children Dancing [in hand-tinted colour]; Spanish Cyclone Dance; The Execution Of Mary, Queen Of Scots; A Piccaninnie’s Dance; The Burning Of Joan Of Arc; A Highland Dance; Death Scene from ‘Trilby’; Lynching Scene; The Duel; and the Finale, A Skirt Dance by Arabella [sic, also in colour].’ There was also the hope expressed that the following week’s programme would include the sporting sensation of that summer; the Derby win of Persimmon, the horse belonging to the Prince of Wales.

Identifying films of this vintage is not the easiest matter. The films themselves had no title cards, so they were called whatever the showmen (or journalists) wanted to call them on any given day. And the latter could make mistakes; that dancer was Annabelle Moore, for instance. But comparing the titles to Victorian film catalogues, we can be pretty sure about most of them. That was Dr Coulton, the Laughing Gas pioneer, doing the dentistry; The Blacksmith’s Shop, The Wrestling Dog, the Cyclone Dance [featuring Lola Yberri], The Executions of Mary, Queen of Scots and Joan Of Arc, the cowboy Lynching Scene, the Trilby Death Scene and Annabelle’s Serpentine Dance are all Edison Kinetoscope titles from 1895 or even 1894; as would be the Boxing Burlesque if it turns out to be the Glenroy Brothers, and The Highland Dance to be The Jamies’ Burlesque Scotch Dance. There were so many titles of men in blackface dancing that the Piccaninnie Dance cannot be definitively identified, but, yes, Edison is one of the culprits. Likewise, the Three Children Dancing title is so vague that it eludes nailing down. The Duel is probably Duel Between Two Historical Characters, another Edison from 1895. Of all the films mentioned, only five survive today.

One hopes that the films went down well with their audience. It was a week of heatwave, nationally, but with 91 degrees Fahrenheit being recorded in Bristol, it was not propitious weather for the business of any hall, however well ventilated and however novel the attraction. But Mr Rosenberg and his machine did stay at the Tivoli for a second week, in a different format. This time they were part of a general variety programme with longer, twice-daily shows, from 7 to 9pm, and 9 to 11pm, shared with a couple of comedians, a couple of vocal acts, and Mr Walter Lynn, now doing double duty with his magic act. The Derby film was acquired, one assumes from R W Paul, and shown. The Wednesday was a special evening, with Mr Leon having a Benefit Night.

There was to be no third week. However, possibly thanks to Mr Leon’s other role as the provincial representative of Lofthouse and Co’s Musical and Variety Agency, Augustus and his apparatus did not have to go too far. The following week, starting June 22, he would appear at the Ball Room of the Assembly Room, Bath, being a debut for cinema there too. ‘The coolest, pleasantist room in Bath,’ says the advert in the local weekly, The Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, as the heatwave continued. Admission 6d, Front Seats 1s. This wasn’t reviewed locally the following week, as the show had moved on. There is a brief report in The Era, which (erroneously?) attributes the film of The Serpentine Dance to Loie Fuller. That would be a Lumière film, and brand new, if true. It might have been a new acquisition, or it could still have been the Annabelle Moore, Edison-made film.

So what do we know of Augustus Rosenberg? Not a great deal . . . but what we do know is interesting and that will be in Part Two.

Mark Fuller is a retired bookie and has been involved with the silent film scene in Bristol for over 20 years, helping out at Bristol Silents, Slapstick, and now South West Silents. He’s a regular at many screens in Bristol and at archive film festivals everywhere.