Augustus Rosenberg and his Kineoptograph When Cinema Came to Bristol (Part 2) Mark Fuller

Share this

In Part One I described the first public film screening in Bristol, which took place on 8 June 1896. I now take a closer look at the remarkable young inventor/ entrepreneur who made it happen.

According to our journalist in The Bristol Times And Mirror: ‘Mr A. Rosenberg [. . .] claims to be the originator of this delightful invention. As many as nine months ago he was, he says, showing his invention in the provinces with great success.’ The article gives advance details of a further invention, the Kineoptophone, ‘an arrangement whereby the [unnamed] Living Photograph Instrument will be made to work with the phonograph . . . it is hoped that this will be completed in about a fortnight.’

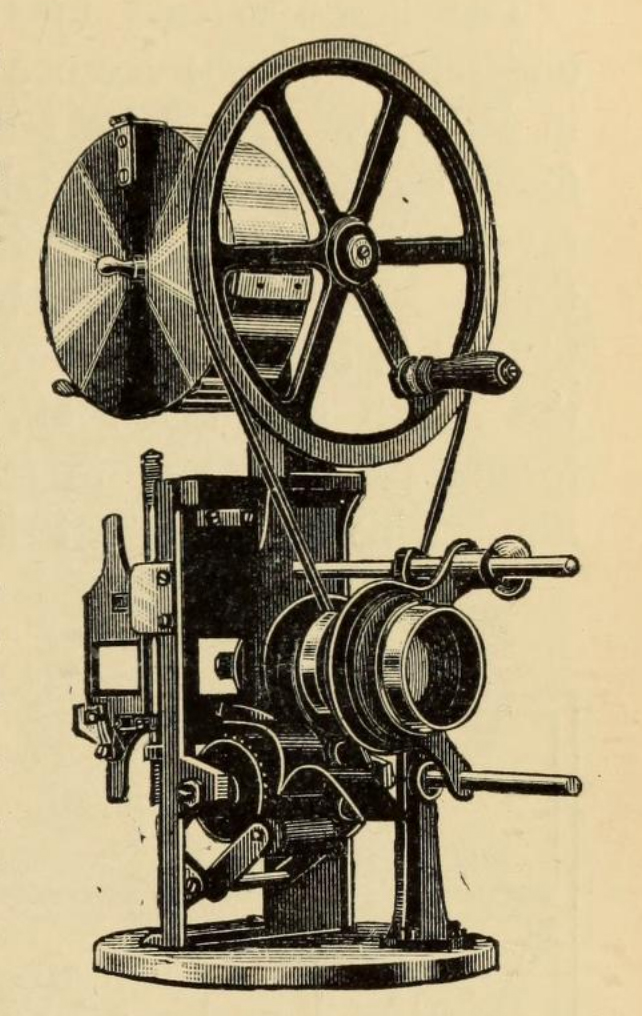

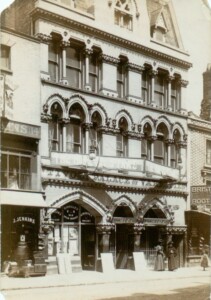

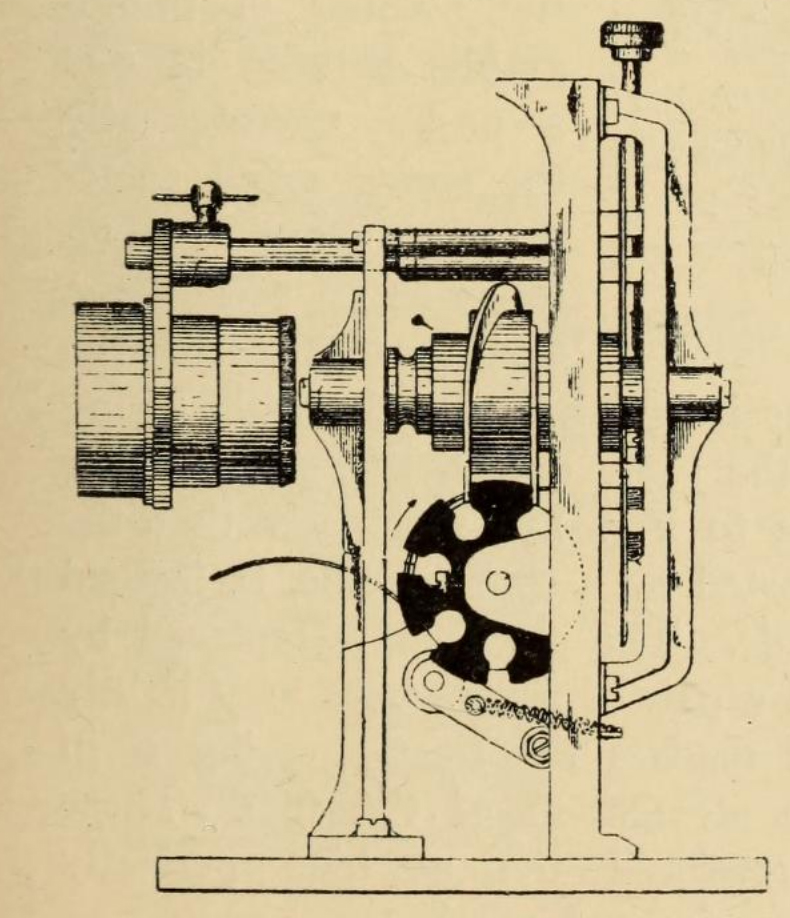

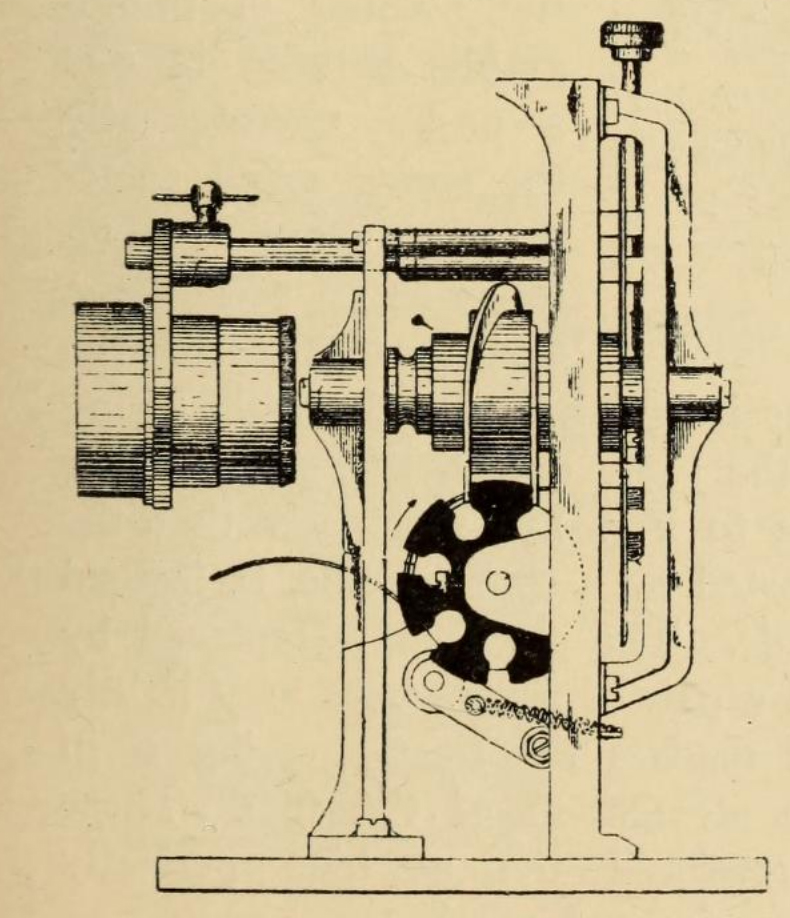

It would be easy to dismiss all this as showbiz hoopla, announced in a darkened room in a provincial city, not to be taken too seriously, by some bloke that no-one has heard of and would never hear of again. But that would be a mistake. For, in John Barnes’ definitive five-volume work, The Beginnings of Cinema in England,1894-1901, is a diagram and an illustration of a projector, from a patent document and a catalogue respectively; the patent, dated 21 July 1896, just five weeks after our first screening in Bristol, is to an Augustus Rosenberg, of Newcastle, and his machine is called the Kineoptograph.

It appears well designed; another engineer called William Routledge is also attached to the patent, together with a business associate, William McDonald. It uses a single helical cam with a star wheel to give the projector its crucial intermittent motion; each hand-driven rotation of the cam would advance the film, by its sprocket holes, and then hold it steady, precisely one frame at a time. Just four days after the patent was granted, two advertisements would appear in The Era; the first, under Music Hall Artistes’ Wants, announcing that the The Kineoptograph was available for engagements, terms negotiable, applications to A Rosenberg of Featherston-chambers, Collingwood-street, Newcastle Upon Tyne. The second advertisement, in the For Sale column, declares ‘A Perfect Machine At Last’. The Kineoptograph was also available as a product for sale to all-comers, for £35, and Kineoptographs made subsequently either in Newcastle or London would remain on sale for three or more years. What was seen in Bristol must either have been a prototype, or an early production model, awaiting the protection of ‘Patent Applied For’ before being offered for general sale.

So, taking Mr Augustus Rosenberg of Newcastle as a serious figure, what do we know of his personal background? Currently, very little. There were at least two well-established Rosenberg families in Newcastle in the mid-1890s; those of educationalist Mr J Rosenberg, who retired as President of the Newcastle Beth-Hamedrash in May 1895; and that of financier Morris Levy Rosenberg, who had his business at 29 Grainger Street West. Augustus, however, was an immigrant, so may not have any connection with them. We know he was born somewhere in Germany, about 1874, to Mendel Rosenberg, an electrical engineer, making him just 22 when he arrived in Bristol in June 1896.

At an engagement in Cork, Ireland, later in the year, he is referred to as ‘Herr Rosenberg’ in the press; as late as 1902, he describes himself in a US patent document as ‘A Subject of The German Emperor’; in 1904 he describes himself in another US patent application as ‘A Subject of The King Of Great Britain’, so presumably he had become naturalised between those times. Newspaper reports of him from Germany in the 1910s describe him as an ‘English Engineer’. He was living in London by the time of the 1901 census, as a lodger with another Newcastle family who had also recently moved South, that of William McDonald; his business associate named in the patent for The Kineoptograph. In Spring 1909 he married Nellie Butterworth, daughter of a Bournemouth hotelier, and with whom he had a daughter Vera in 1910, and a son David in 1911.

The earliest newspaper reference to Augustus Rosenberg found so far is in The Daily Gazette For Middlesbrough 21 March 1895. It was reported that at The Stockton Industrial And Art Exhibition ‘Messrs. Rosenberg and Co of Newcastle are showing Edison’s latest Kinetoscope, in which 2,760 views can be seen in one minute . . .’.

So Rosenberg certainly had a long-standing interest in moving pictures; but trawling through The Era for 1896 I found no evidence whatsoever for his nine months of provincial screenings. I was almost ready to dismiss this as ballyhoo, trying to establish some sort of primacy for his invention in the minds of his Bristol audience. However, during a conversation with Deac Rossell, he pointed me to an article by Denis Condon; in May 1896, the Rosenberg & Co team had been in Dublin for a fortnight. Somehow totally ignored by The Era, which otherwise gave good coverage of events in Ireland, from the 19th to the 25th of May 1896 a charity bazaar was held in Ballsbridge, Dublin, called Cyclopia.

Put out of your minds what you may think a charity bazaar was. Cyclopia was an immense undertaking, an event advertised all over the country. More like an urban version of a county fair, it was in aid of the building of a new eye hospital, and the target was a colossal £10,000 in 1896 money. Opened in person by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, with special trams laid on for the expected visitors, it ran daily from 2.00pm until 10.00pm for a week. There were fairground rides, a water chute boat ride, tethered hot-air balloon flights, huge firework displays, concerts of all types, dance exhibitions and public dances, cafes and restaurants, stalls and raffles run by the gentry from all over Ireland. Displays of new technology included Roentgen (X) Ray demonstrations, phonographs, kinetoscopes . . . and projected moving pictures, from Rosenberg & Co, showing between dancing displays in one of the large halls.

The show was brought to Cyclopia by Mr C A James, proprietor of the World’s Fair Waxwork Exhibition; part waxworks, part music hall, and like our Tivoli, small and not quite of the first rank. It operated above a ‘Tuppenny Shop’ (aVictorian ancestor of our Poundlands) in Henry Street, Dublin. The programme advertised is 90 per cent the same as in Bristol; Zaro the Tumbling Clown and Interior of a Whiskey Saloon joining (largely) the same Edison titles as at the Tivoli, minus a few films (The Duel, for instance, not being advertised). On the first day there were technical issues for a while at least, mentioned in passing by the Irish Daily Independent, but the other newspapers gave glowing reviews. It must have been a popular success, as on its first full day of operations it performed only two shows, but that increased throughout the week until by the Friday it was performing nine shows in the day, to capacity crowds and with people locked out.

As in Bristol, it was advertised as an Animatographe, and being as seen at the Alhambra, London; but as this was just three weeks before the Bristol screenings where we know it was the prototype or pre-production Kineoptograph, I’m sure that this was the case in Dublin too. I think that this is one of Rosenberg’s ‘provincial’ (with apologies to any Irish readers) shakedown screenings while he was waiting for his patent application to be processed. There seems to be no evidence that Rosenberg ever purchased a Paul Animatographe, which were, in May 1896, still rare beasts. Just six weeks earlier, Carl Hertz had purchased one by removing Paul’s spare machine from the stage of the Alhambra, before introducing cinema to South Africa, and then Australia, with it. But it is impossible, at the moment, to be certain.

Cyclopia finished on Whit Monday Bank Holiday, and the team moved on to the World’s Fair Waxworks for the remainder of the second week. James advertised the attraction as ‘The wonderful triumph of scientific research [. . .] which has been patronised by the nobility and gentry of Ireland at Cyclopia’, so he was keen to advertise to a better class of patron, or those wishing to be, on the back of his generosity. As in the second week in Bristol, [Dr] Walter Lynn Jr is advertised amongst the additional acts as an illusionist and conjuror, so was probably doing double-duty as the films’ narrator too, and one assumes Rosenberg is at the controls of his yet-to-be-patented machine for the twice-daily programme. Annoyingly, what seems to be the only extant review of the film element of the show at the World’s Fair, in the Dublin Evening Telegraph, turns out to be a verbatim cut-and-paste steal from The Freeman’s Journal review of the show at Cyclopia, published the week before.

However, I have found no other hard evidence, yet, for Rosenberg’s claimed nine months of provincial screenings apart from those appearances in Dublin. It may be possible that he somehow flew under The Era‘s radar by specialising in bazaar screenings, or just giving private shows in an experimental phase, but at a time where there were just three active projectors in London, only rare sightings of (allegedly) Lumière machines in halls elsewhere between March and May 1896, and prior to March screenings only happening in scientific institutions, its extreme novelty would have drawn some attention, one would think. The jury is still out on Rosenberg’s nine-month claim . . . but it does look dubious to say the least. There are scientific journals of the period that I’ve been unable to consult, but that will have to wait.

So, how did Mr Leon of the Tivoli and Augustus Rosenberg get in touch? Rosenberg wasn’t advertising his show, or his product, or being mentioned in reviews in The Era prior to his Bristol engagement. Well, Leon placed a small advertisement in The Era of 30 May 1896: ‘Wanted; Stars and specialities of all descriptions for [weeks commencing] June 8th, 15th. Apply with lowest terms to Leon, Tivoli, Bristol, or Lofthouse, London.’

Miss H W Lofthouse was a musical and variety agent with her own company based in Lambeth; our Mr Leon is mentioned in their advertising as being their ‘Provincial Representative’. It’s conjecture on my part, but it seems a distinct possibility that Rosenberg answered this advertisement, which covered the precise weeks of his engagement. Leon, having a foot in a theatrical agency, was not generally one to waste money advertising for acts unless he was really struggling to fill a slot at the Tivoli.

It would be a few months later, in October 1896, after the heat of that summer, when films did return to Bristol. . . but this would be Paul’s Theatrograph, shown as part of a variety programme at the People’s Palace. It would be a good while before it would become apparent that these amusing music hall turns would sound the death knell for music hall itself. The Tivoli would succumb to the inevitable, long before that, in 1902. Its Bristol competitors, the People’s Palace and the Empire, would become cinemas in turn, as would, for a while, the still yet-to-be-built Hippodrome.

Rosenberg himself remains elusive. After a few more known engagements in 1896, at another huge bazaar in Cork, weeks at Harrogate, Derby and a fortnight in Middlesbrough, did he concentrate on his new projector manufacturing business, or his inventing behind the scenes, or just putting on his shows? Evidence either way is slight.

After that initial advertisement in The Era in July, there is no further advertising until December 1896, where his Kineoptographe is rebranded as ‘Rosenberg’s Improved Cinematographe’, again, both for sale and for event bookings via an agent. This rebranding as a Cinematographe, the name of the Lumière brothers’ design but already becoming a generic term for all projectors, may have made business sense but it does nothing for his posterity. It obscures what success his machine may have achieved subsequently in archival sources; if a reporter of the time neglects to mention Rosenberg then the machine would be assumed to be a Lumières’ product from France. Similarly, I can find no hard evidence that Rosenberg & Co either made or commissioned any films themselves, which might have been both a good business move and another reason to be remembered.

Rosenberg & Co branched out in 1897 and 1898, becoming suppliers and showmen for all sorts of mechanical entertainments; ‘Scientific Novelties’ as their advertisements described them. By February 1898 they were advertising, from their new base in London’s Southampton Row their ability to deliver or show Ives’ Photo-Kromskop. This was a stills projector that utilised filters and mirrors to project full, natural colour photographic images, on the same scientific principal that would later be used by three-strip Technicolor for moving pictures. They also advertised Wireless Telegraphy, Gugliemo Marconi’s early radio, with a range then claimed of up to four miles. For smaller pockets there was the Pocket Kinetoscope (what we now call flick books); six stamps would obtain two samples for prospective salesmen. They had also started to deal in the machines and films of their more famous competitors from abroad. Edison and Lumière films and machinery are being offered alongside Rosenberg’s own invention, and the range of sound machinery of the era; the Phonograph, the Gramaphone (sic) and the Graphophone.

Longer term, it seems likely that Rosenberg did indeed pursue his dream of supplying sound to his projected films. There is a court case in September 1899 where A Rosenberg and George Scott are sued by the Edison-Bell Consolidated Phonograph Company for dodging public-use license fees for a Graphophone Grand; a not-inconsiderable sum of £50 on top of the £60 cost of the machine, at a time when £100 a year was seen as a living wage. The Graphophone Grand was a beefed-up, large-format phonograph designed for theatrical and entertainment use, and unsuited, by dint of its sheer power, for domestic use. Rosenberg and Scott’s partnership seems to have been short-lived, as by 1904 Scott turns up as a film exhibitor in Ontario. In Canada he is seen as one of their film pioneers; later he was the cameraman on Gaston Melies’ South Pacific and Far East cinematic expeditions, before being employed at Inceville, and on early John Ford Westerns.

Rosenberg was one of those Victorian polymath inventors, with parallel interests in mechanical, acoustic, electrical and chemical engineering. He had further patents to come, branching out from the world of film, but with one foot still in it. In 1902 a patent for a film camera using half the width of a reel of film in one direction, then reversing it automatically to expose the other half. In 1903 for a portable oxygen-generating device. In 1909 an amplifier for the phonograph, and a hearing aid using bone conduction. In 1910 a home electroplating system for his Galvanit company got a huge amount of press coverage internationally. A two-track stereo sound system for film in 1911. In 1912 an amplified telephone receiver for the deaf, and an electrolytic metal cleaning system. There were others but all this activity goes quiet after World War One.

Rosenberg himself had moved from Newcastle to London with his business in the late 1890s, initially lodging with his old business associate William McDonald (now running a laundry) and his growing family, according to the 1901 census, and in the 1910s to Bournemouth with Nellie and their children. In the 1920s they inherited her parents’ property, the Tollard Royal Hotel on West Cliff, and spent a considerable £80,000 on refurbishing and expanding it. They ran it from then on, living on the premises. Nellie was probably the hotelier of the pair, but Rosenberg did install his 1928-patented Solarium. Resembling an artificial beach in a greenhouse, with sunshine flooding in when available, ultraviolet sunlamps reflected off a diffusing metal ceiling when not and underfloor heating beneath the sand and pebbles, it was no longer dependent on the vagaries of the Bournemouth climate. He was also, alongside Nellie, director of a local cinema, the 125-seater Premier News Theatre, opening in 1936, returning him at last to the cinema business.

The Rosenberg family turns up on ships’ manifests throughout the 20s and 30s; sometimes just Rosenberg on business trips to engineering companies in the US; sometimes family pleasure trips, like a Mediterranean cruise, and in 1936 a five-week cruise that ended up in San Francisco. They repeated that trip in January 1937, seemingly for his health, once more on the Arandora Star departing from Southampton. However, Rosenberg never returned. Between Honolulu and San Francisco, on February 10th 1937, he died on board from heart failure, and was buried at sea. He was 63. His obituary in Kinematograph Weekly was just four sentences long and mentions his News Theatre in Bournemouth as if it were his only connection to the film industry.

They should have consulted their own back issues. In 1910 Kinematograph Weekly had run an occasional series called Picture Pioneers; in it, a series of industry veterans – of 14 or even 15 years standing! – reminisced and pronounced on the future of film. Appearing in their March 31 issue, pioneer number three was one Mr William McDonald; Rosenberg’s one-time Kineoptograph co-patentee and London landlord. It’s conversational and anecdotal but is full of interest for that year of 1896. McDonald, it seems, had been a magic lanternist in Newcastle when he went into partnership there with Rosenberg, ‘From which centre we worked the whole of the North of England,’ he says, citing music hall managers and entrepreneurs Thomas Barrasford and Lindon Travers amongst others.

Barrasford ran the Palace Theatre of Varieties in Newcastle, and as far as I can ascertain was the first to host projected films in the UK and Ireland outside of London, at the very early date of 26 March 1896. It was billed as The Original Cinematographe, as it would be a few days later at the rival Empire Theatre, but both the advertising for and reportage of the events neglect to mention any associated showman or company involved. I’m not claiming these screenings for Rosenberg. McDonald is imprecise about when they worked with Barrasford, and the programme of films has little in common with what we know to be Rosenberg & Co’s repertoire. But I can’t rule them out entirely either. It may be that Barrasford had bought the machine himself, perhaps from the Lumières in Paris, as in early May 1896 a machine was being advertised for sale, in The Era, under his name. McDonald mentions being involved with Barrasford (and his mezzo-soprano wife) at the opening of the Spa Theatre, Bridlington, which would have been 27 July 1896, but The Era‘s report is perfunctory, and the local paper Bridlington and Quay Gazette is missing for that month in the online archive.

In mid-1896 Lindon Travers was the experienced general manager of the Olympia, Newcastle, with a sideline as a singer and elocutionist, a reciter of poetry or prose. As he had spent the summer of 1896 in South Africa, and the remainder of the year and the beginning of 1897 as a touring lecturer on that country, we might assume that the dealings with Rosenberg & Co date from the first half of 1896 when he was in charge of the Olympia. Again, I can find no hard evidence of this, but in April 1897 Travers advertised his show as including moving pictures of the Nansen Polar Expedition provided by his ‘Traverscope’. This could be what McDonald is referring to. If the name Lindon Travers is familiar, there was a film actress called Linden Travers in the 1940s and 50s; she, and her even better-known brother, Bill, were this Lindon Travers’ grandchildren, and both had Lindon as a middle name.

McDonald claims, not entirely correctly, that Rosenberg & Co had shown the first films in Ireland at Cyclopia (a Mr Doyle had beaten them to it by a few weeks at the Star Theatre, Dublin), and mentions the dates at World’s Fair, Cork and another event in Limerick. This latter proved eventful. Described as a Protestant Bazaar, for it they had ordered from Birt Acres his film of the Prince of Wales opening the Cardiff Exhibition in June 1896; but upon the screening of this patriotic topical film a riot broke out, windows were smashed, and chairs thrown at the screen. They quickly pulled the film, and the band regained order by playing ‘Yankee Doodle’ . . . but the rest of their stay was highly successful.

As well as purchasing films from Acres, he mentions visiting and buying films from a Miss Rosie Rosenthal at her film depot Old Broad Street in London. Rosie can only be his, or the trade’s, nickname for the famous Alice Rosenthal. She ran the film sales department of Edison’s men in Europe, Maguire and Baucus of Broad Street, thus explaining the reliance of the early Rosenberg shows on Edison’s film product. In 1897 Maguire and Baucus’ new manager, Charles Urban, would move the business to Warwick Court, where it would become the Warwick Trading Company, and the dominant film distributor in the UK of this era. In 1903 Urban would set up his own company that in turn would become a huge force internationally for the next ten years; but each time he moved, making sure he took Alice Rosenthal with him as a key member of staff, alongside her brother Joseph, pioneer war cameraman, remembered for his filming of the Boer War, Boxer Rebellion, the Russo-Japanese War, and later the Great War.

McDonald also explains, with some regret, the demise of Rosenberg & Co:

‘Mr Rosenberg having science rather than showmanship in view, and my own inclinations being somewhat opposed, we made the fatal mistake of disolving [sic] partnership and dropping a business which if continued would today be worth many thousands of pounds.’

Seemingly his laundry business mentioned in the 1901 census had been either temporary or a sideline; from Rosenberg’s he joined R W Paul’s business, and by the time of the article was running a film and lanternists suppliers, the City Sale and Exchange, with three premises in London. In the 1911 census he would be described as a ‘Cinematograph salesman’.

There should be more to discover about Augustus Rosenberg; archives and libraries are still locked down for research purposes, so all this information has been culled from either online resources or books on my own shelves. I hope to continue discovering more about this fascinating figure when normality returns.

His Kineoptograph, which had caused such a stir in Bristol in 1896, may not have become a major factor in the industry. Nor did it become one of the generic terms for film projectors, but it did introduce the experience of filmgoing to people here in Bristol and in other towns and cities both in the UK and Ireland. He stopped advertising it for sale after a couple of years, and it was soon forgotten, even by historians of the period. However, one example does survive into the twenty-first century; dated to 1896, it’s currently in private ownership. How tempting it is to think that it might be the machine from the Tivoli. . .

Bibliography and Acknowledgements

Kathleen Barker Early Music Hall In in Bristol Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1979

Kathleen Barker Entertainment in the Nineties Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1973

Kathleen Barker Bristol’s Lost Empires Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 1990

John Barnes The Beginnings of Cinema in England 1894-1901 (5 Vols) University of Exeter Press, 1996-98

Richard Brown and Barry Anthony The Kinetoscope, A British History John Libbey, 2017

Ian Christie Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema University of Chicago Press, 2019

Denis Condon ‘Baits To Entrap The Pleasure Seeker’ in Beyond The Screen; Institutions, Networks and Publics of Early Cinema Indiana University Press, 2012

Robert G Clarke In Search Of George Scott Ontario Historical Society (Online)

Stephen Herbert and Luke McKernan Who’s Who In Victorian Cinema British Film Institute, 1996

Stephen Herbert Victorian Film Catalogues, Facsimiles from The WD Slade Archive The Projection Box, 1996

Luke McKernan Charles Urban University of Exeter Press, 2013

Luke McKernan ‘Colourful stories no. 2 – The Kromskop’ in his blog The Bioscope

Charles Musser Edison Motion Pictures, 1890-1900 Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997

Harrogate Advertiser, at Harrogate Library

New Scientist, via Google

The Era, Bristol Times and Mirror, Bristol Mercury, Bristol Magpie, Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, Daily Gazette for Middlesbrough, Newcastle Daily Chronicle, Irish Times, Irish Daily Independent, Dublin Evening Telegraph, Dublin Daily Express, The Freemans’ Journal, Bournemouth Graphic, Cork Constitution, et al via The British Newspaper Archive.

The Times, Illustrated London News, via Gale

Reports of Patent, Design and Trade Mark Cases, via Intellectual Property Office at Oxford Academic

Patent documents via Espacenet.com and The Internet Archive

Tollard Royal Hotel details from www.flickr.com/photos/alwyn_ladell

Specific references available on request.

Grateful thanks for their generous help and advice to; Robert G Clarke, Dr Denis Condon, Tony Fletcher, James Harrison, Stephen Herbert, Avril McKean at Harrogate Library, Melanie Kelly, Dr Carol O’Sullivan, David Robinson, Deac Rossell, and especially to Janice Healey and Rodney Hillel Tryster for their genealogical expertise here and in Germany.

Mark Fuller is a retired bookie and has been involved with the silent film scene in Bristol for over 20 years, helping out at Bristol Silents, Slapstick, and now South West Silents. He’s a regular at many screens in Bristol and at archive film festivals everywhere.