When Bristol Became Interesting

Share this

In the nineties, the old Bristol faded away and a new one took its place. Suddenly it became a visitor destination in a way that the old Bristol never was. Eugene Byrne reflects on this heady transformation.

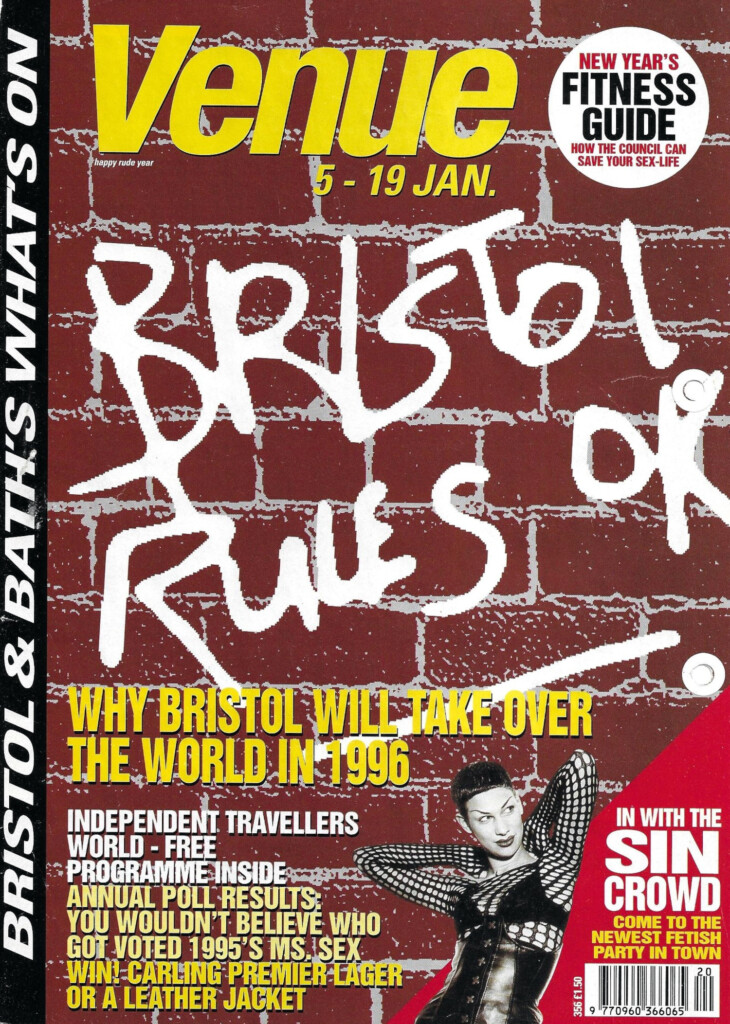

BRISTOL IS BUZZING – it’s official. Trendspotters, spin doctors, masters of hype and media types are now tuning in and turning on to the Bristol vibe. A couple of years back these very same folk would have vaguely placed Bristol in Wales and shown a polite disinterest at the mention of the name. ‘Oh, Bristol, that’s got a suspension bridge, hasn’t it’ was a fairly typical comment. Now there is a new respect for what was once perceived as a carrot-crunching backwater, an armchair city of also-rans…

As Bristol-dwellers know, there’s much more to the city than trip-hop and Gromit. It’s the LA of the UK, a slow simmering melting pot that’s boiled up a profusion of weird club styles … Like the weird and wayward beasts that evolved in the isolation of the Galapagos Isles our local talent has developed far from the madding mainstream.

That was local listings magazine Venue in January 1996, and even allowing for journalistic hype, it was still saying something significant. Bristol had been transformed.

Well within living memory, the old Bristol faded away and a new one took its place. The old Bristol was a hard-working, sensible, in-bed-by-ten-on-Sunday-evening kind of place. It had an ancient port at its heart which had been there since medieval times and it had long since also been one of the manufacturing powerhouses of England, famous for engineering, tobacco, booze, packaging and more.

Most of that has now gone. The Bristol of today is all about IT and media, finance, education and advanced technologies in several fields. But it’s also about leisure, fun and creativity. It’s a visitor destination in a way that the old Bristol never was.

Some would also have you believe that Bristol has an exceptional ‘tradition’ of riot and disorder, though nobody particularly believed that until the noughties.

If, in 1980, you had suggested that Bristol had a track record in working-class agitation, any historically literate person would have agreed, but would then have pointed out that Glasgow, or the port cities and industrial centres of the Midlands and North of England, had rather more form.

If, in 1980, you’d suggested that Bristol would be a major visitor destination for those who were not particularly interested in hot air ballooning or powerboat racing, you would have been laughed at.

And yet in October 2002 we learned that Bristol had made the shortlist for 2008 European Capital of Culture. This might not sound like a big deal nowadays, but it surprised a lot of local cynics at the time. (We still lost, mind.)

There’s no one point at which the old Bristol died and the new one was born, though if you want a big, spectacular historic moment, set the time-machine for 7am on Sunday 29 May 1988.

That was when 500 kilos of gelignite were detonated to reduce the old bonded tobacco warehouses on Canons Marsh to heaps of rubble under a cloud of dust that took ages to settle. The biggest controlled explosion in Europe since the Second World War, or so we were told.

The tobacco bonds were wiped away to make way for part of what we now call ‘Harbourside’, specifically the site of the new Lloyds Bank HQ and the amphitheatre in front of it. Dead symbolic, it was: out with the city docks and manufacturing, and in with finance and leisure.

A big bang moment. Tobacco Bonds demolished in 1988 to make way for a bank HQ and the Lloyds Amphitheatre. (Credit: Bristol Post)

This was a big bang, but not a creation-of-the-universe Big Bang. Many of the processes involved in the making of the new Bristol were already well under way, with more and more parts of the once-derelict city docks being redeveloped. And there was still more to come.

Besides, the new Bristol was never just about new buildings and the replacement of blue-collar industries with white-collar ones. It was never just about decisions made by the council, or Whitehall or Arts Council England or in corporate boardrooms. A critical part of the new brand would be about things that came from the bottom up rather than top down. The art, the street art, the music, the theatre and, if you like, the revolt, all came from below; mostly, but not exclusively, from young people with middle-class backgrounds.

There was no cultural ‘big bang’, though you can point to a few moments. How about Wednesday 4 August 1983, the day the Thekla berthed in the city docks?

Shorthanded by the local media at the time as a ‘floating arts centre’ the good ship, initially fronted some of the time by the famously eccentric Vivian Stanshall, would go on to become a place of all manner of wonderful happenings.

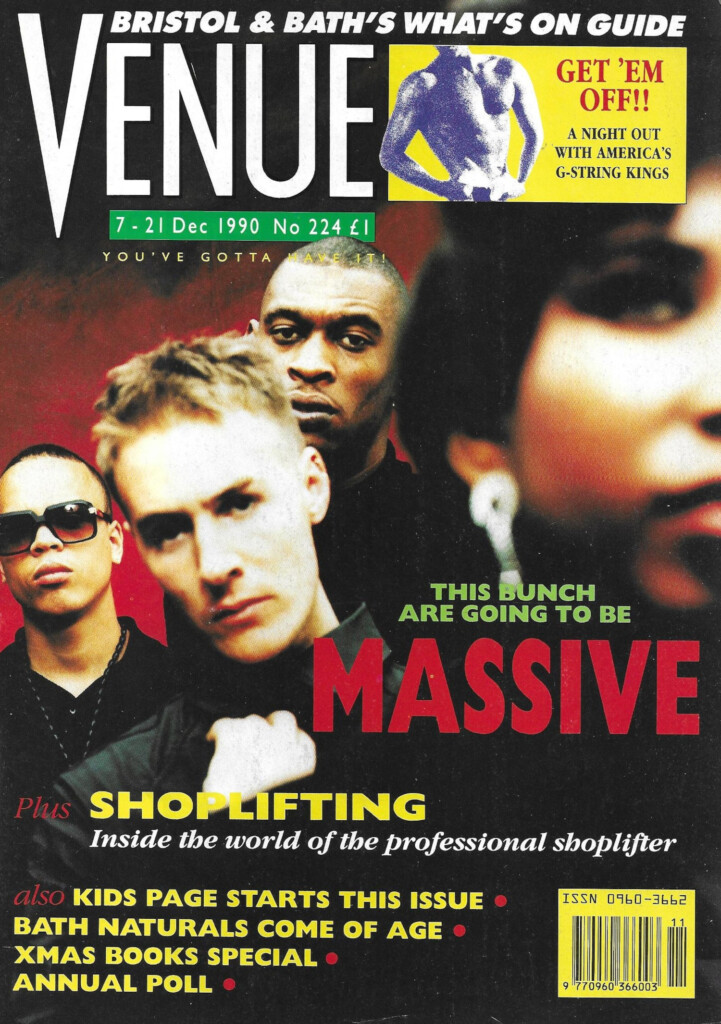

Or would it be the release of Massive Attack’s Blue Lines in April 1991? Or maybe the opening of the ‘Graffiti Art in Bristol’ exhibition at Arnolfini on 13 July 1985? People would still be prosecuted for spraying pictures on walls for years to come, but that marked the point at which the chattering classes embraced what most at the time considered a bold and radical new art form.

“This Bunch are going to be MASSIVE” said Venue in December 1990. And they were.

With the end of the old manufacturing industries in the 1970s and 1980s, old warehouses and factories were demolished and the brownfield sites redeveloped (as the Bristol Development Corporation did around the St Philips area), or buildings were repurposed as apartments, offices, bars and cafés, as happened around the City Docks.

Bristol was not unique in any of this; similar work was going on in most other cities. Nor was Bristol unique in adapting harbours which had closed for various reasons (a lot of them to do with ever-bigger ships and containerisation) as water features in the middle of town.

‘Yuppy flats’ and housing bubbles happened everywhere. Many cities also got shiny new tram or light rail systems. Bristol didn’t, though consultants, engineers and officials had meetings, wrote things on flipcharts and issued press releases about such things, sometimes accompanied by artists’ impressions or CGI images, for decades afterwards. A cynic might say that planning public transport systems which would never be built was, and remains, a significant local employer.

The physical appearance of all of Britain’s cities changed, but few places changed as much in character as Bristol did.

The one English city which is probably comparable would be Manchester, with its ‘Madchester’ dance/clubs/music scene in the 1980s-1990s and its growing reputation as the ‘gay capital’ of the North. But if your local pride in Pride matters, you can point out that Manchester is considerably bigger than Bristol, so we punched well above our weight.

In all its previous history, Bristol never had a reputation for creativity or in the arts. There were a few exceptions, such as the early nineteenth century ‘Bristol School’ of painters. And, yes, many significant figures in music, literature and art were born in Bristol, but almost all made their careers elsewhere, usually London.

Not long before new Bristol emerged, we had produced one of the most influential partnerships in popular music history; songwriters Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway. If you’ve never heard of them, ask Wikipedia, and prepare to be astonished at the number of hits they wrote and/or performed. A little later, Bristol also produced two-thirds of Bananarama, the biggest-selling all-female British group in history.

None of the above, and many others were known as Bristolian acts. That all changed in the 1990s, following the success of Massive Attack, Portishead, Roni Size, Strangelove and many more. People talked of ‘Bristol’ bands, producers and DJs, and a scene which also included PJ Harvey (from Dorset, but hung out here a lot, so ….)

Tricky, a Knowle West boy, and a bit of an outlier in the ‘Bristol sound’ (whatever that was) had a bit-part in Luc Besson’s 1997 sci-fi spectacle The Fifth Element, making him the first person with a genuine Bristol accent to ever appear in a big Hollywood flick. Though far more Brits (and Bristolians) noticed BBC medical drama Casualty, co-created by Paul Unwin, Artistic Director of the Bristol Old Vic, and which premiered in 1987.

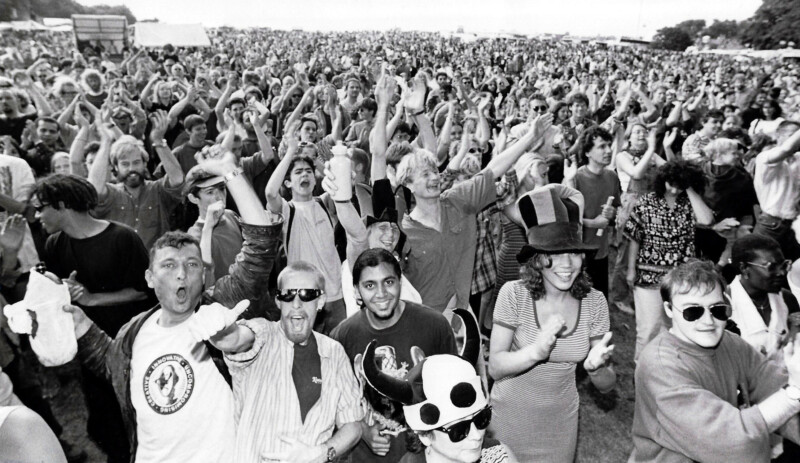

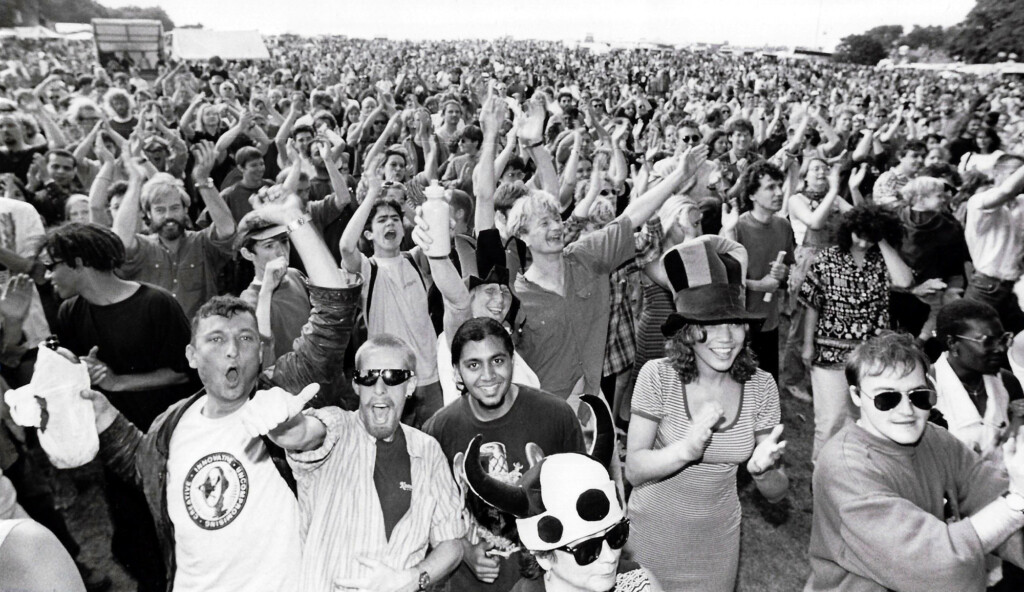

The Bristol region also had something of a national reputation for outdoor festivals since the 1970s and, in the late 1980s/1990s, its outlaw-tinged free party scene. This was also when the annual Ashton Court Festival, showcasing (mostly) local bands, DJs and performers, was in its pomp.

Ashton Court Festival, 1996. A huge free party for Bristol every summer showcasing local acts. Later stymied by rising costs, it put the city on the UK’s cultural map in the 1980s and 90s. (Credit: Bristol Post)

At the same time, there was that street art thing going on, while Artspace had been providing affordable studio space for artists, sculptors, printmakers and more since the 1970s.

Running in parallel with the street art, often involving some of the same individuals, was a phenomenon which has been almost completely forgotten nowadays – pirate radio. Not ships in the Bristol Channel, but people setting up atop tall buildings and broadcasting music, often local, or of niche appeal, to an area smaller than a postal district for a few hours at a time. Technology erased pirate radio, but should you be into family trees or Venn diagrams, you’ll find that many pirates came from the same people and places that produced the music and murals.

Politics and ideology underpinned most, perhaps all, of this cultural explosion. The graffiti and the airwave piracy and many of the free parties (‘illegal raves’ in tabloid-ese) knowingly broke the law, while much of the music came from the streets. And let’s not forget that from 1979 until 1997 the Conservative party was in charge.

From the St Pauls disturbances of 1980 onwards, there was also a growing awareness of the great stain on Bristol’s history. The 1996 Festival of the Sea, a hugely successful promotion of the city as a place to visit or do business, was singularly ham-fisted in not acknowledging the transatlantic trade. This did not go unnoticed and three years later, a major exhibition titled ‘A Respectable Trade’ at the City Museum laid the story out for all to see. It would be another 21 years before Colston’s statue fell, mind.

Why and how all of this cultural change happened, and why it happened in Bristol has dozens of explanations.

For one thing, the de-industrialisation and the declining power of Bristol City Council, which saw everything from its council housing to the port and airport privatised and which was deprived of funding and powers by successive central governments, generated spaces in which interesting things could happen.

Bristol’s ethnic diversity and its relatively small size meant that people from a wide range of different cultural backgrounds could intermingle and collaborate relatively easily.

Liberalisation of the laws on homosexuality had happened in the 1960s, but old attitudes were slow to change. While more and more people began to ‘come out’, those living in smaller towns in the region often gravitated towards Bristol as it was a more comfortable place to be themselves, and where they would find a vibrant social scene.

Another key factor was the establishment of the Bristol Cultural Development Partnership (BCDP) in 1993, a collaboration between business, the City Council, Arts Council England South West and, in more recent years, both universities. BCDP made a load of things happen, from the celebrations of Brunel’s bicentenary (2006) to Great Reading Adventures and much else, as well as leading the European Capital of Culture bid. BCDP head Andrew Kelly was dubbed ‘Bristol’s Mr Culture’ by one local magazine, but given his talent for fundraising, a generation of local artists and cultural entrepreneurs saw him as Santa Claus.

Perhaps most crucial of all was the fact that we had two universities, three if you count the forerunner of Bath Spa University, many of whose students lived in Bristol. And as we all know, a lot of them stay on after graduating. Not all were rich, pampered kids who lounged around all day smoking dope and talking rubbish about projects they’d never get off the ground (though, let’s face it, a lot of them were).

By the time of the 1991 census, we knew that Bristol was the English city with the highest proportion of graduates outside London – ten per cent educated to degree level or higher. It wasn’t just that some of them went into local creative industries – most did not – but they formed an appreciative (and affluent) audience for a lot of what was going on.

(The 2021 census revealed that 42 per cent of Bristolians have degrees or higher qualifications. Bristol is still the most educated of all the ‘core cities’ of England and Wales.)

For the would-be historian of Bristol culture in the 1980s and 1990s, there are plenty of sources – some books, old newspapers and the memories of those who were there. But the best source of all is Venue magazine, published fortnightly (later weekly) from 1982 to 2012. As a listings magazine, it covered all aspects of local culture, entertainment and lifestyle. It was written and compiled by people who really knew their stuff. What’s also telling, though, was that it survived so long as England’s most successful listings magazine outside of London because there were enough people who wanted to buy it to keep it viable. The 1980s, particularly, saw similar magazines being set up in other cities, but few survived very long, though the one in Manchester, City Life, prospered for about 20 years – but that was in a considerably bigger city.

Educated, politically progressive, ethnically and socially diverse, plus an environment with a lot of gaps and cracks which could be filled with interesting stuff – maybe that’s how it all happened.

Bristol is probably now changing in character once more. Exactly how, and whether it’s for better or worse, remains to be seen. The problems we face at the moment – particularly the ridiculously high rents and house prices – are partly down to the successful transformation of Bristol in the 1980s and 1990s.

The brand became official, taken up by property developers, council leaders and tourism bosses alike, creating demand among people who want to live in Bristol because they believe it’s cool and edgy. Perhaps it still is. Or maybe the brand has long-since become just, well, marketing BS, and maybe we need another big explosion like that one in 1988.

A scene that came up from the streets became part of Bristol’s branding. Developer’s advert from 2015. (Credit: Eugene Byrne)

This article appears in Bristol 650: Essays on the Future of Bristol, a book bringing together essays from over 30 contributors, addressing some of the challenges the city faces and sharing ideas about how we might meet them. From dealing with the past, the future of social care, culture and housing to building a city of aspiration, the book looks to promote learning about the future of Bristol and encourage new ideas to come forward.

Free copies of Bristol 650: Essays on the Future of Bristol will be available at selected Festival of the Future City events in October 2023, or you can find articles featured in the book at bristolideas.co.uk/bristol650book.