What Was Life Like in Bristol in 1973? The city marked Bristol 600 with extravagant celebrations

Share this

Bristol in 1973 – everything was going to be utterly brilliant. And then it wasn’t. As the celebrations for Bristol 650 get underway, historian and writer Eugene Byrne looks back at what Bristol was like in 1973 – the year the city marked its 600th anniversary.

1 January 1973 was a Monday, and to the surprise of absolutely no-one, workplaces across the country reported high levels of absenteeism as staff phoned in sick in order to nurse their hangovers. It was also the day on which Britain joined the European Economic Community, or what your gran would persist in calling ‘the Common Market’ for years to come. In Bristol it felt as though there were huge changes in the air, all of them for the good except for a big shake-up in local government.

‘Britain’s gone to market’, said the Post’s midday edition, though many Bristolians would have been too hung over to notice (Bristol Post

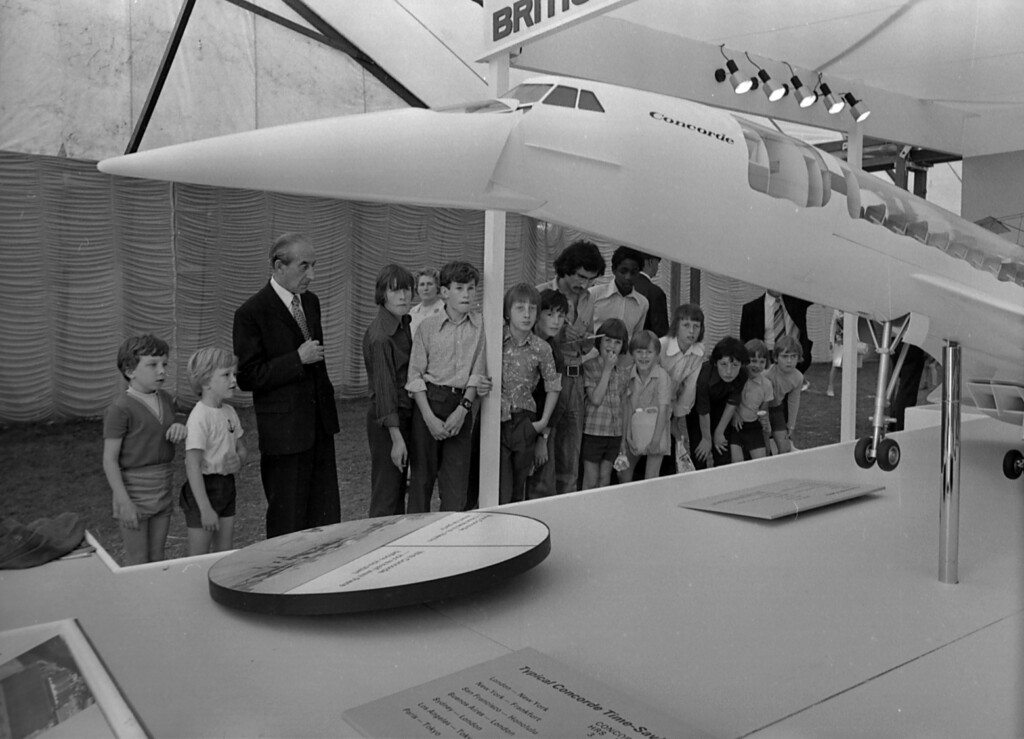

Everywhere you looked there seemed to be progress. It was still possible to believe that the city’s most globally recognisable product, the Concorde supersonic airliner, would be purchased in numbers by several of the world’s major carriers.

And at a time when cars and roads were still broadly seen as a good thing, some looked forward to the completion of the M5 between Avonmouth and Dunball sometime in the summer (actually, they’d have to wait until autumn). Even British Rail’s new Parkway station, opened the previous year and already proving very handy for getting to London, was designed to integrate with the motorway system and car drivers.

Broadmead, though, was to be pedestrianised. It was still unchallenged as Bristol’s principal shopping centre, and better it be congested with shoppers on foot than congested with cars. There was even talk of some of it being roofed over.

In April the new Dragonara Hotel (nowadays the DoubleTree by Hilton) on Redcliffe Way opened, and quickly established its reputation as one of the swankiest places in town. The feature everyone talked about was its restaurant, a glamorous circular structure based on a former glassmaking kiln. The hotel and Kiln Restaurant would in due course attract a steady stream of celebrity visitors.

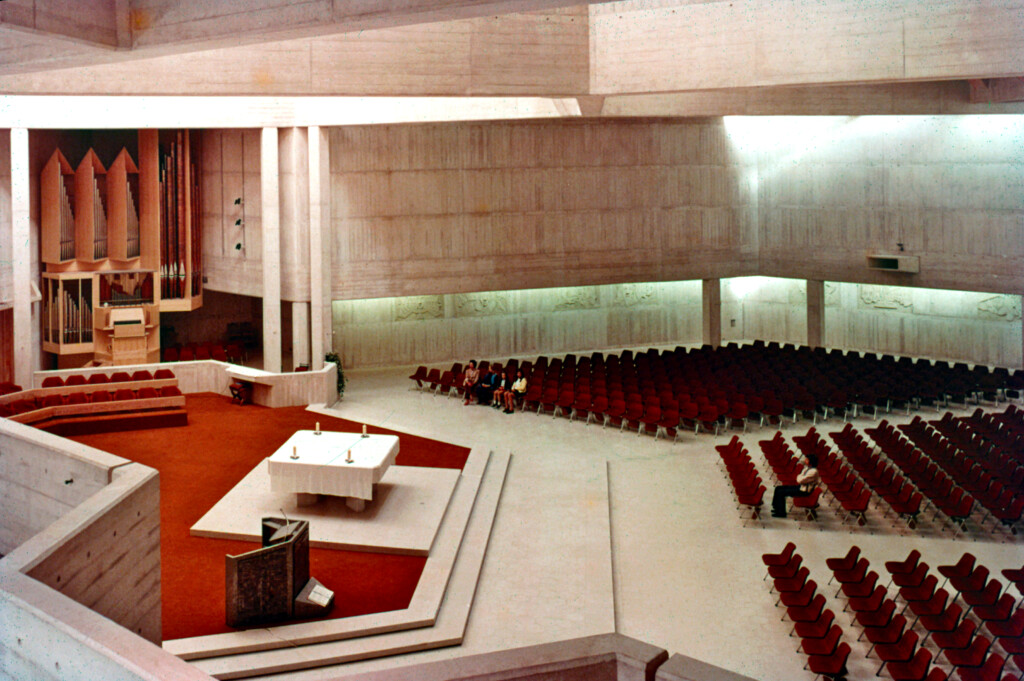

After waiting for more than 150 years the city’s Roman Catholics finally got their cathedral. Consecrated on 29 June, Clifton Cathedral was a triumphant modern building, though it’s fair to say that its design is more appreciated nowadays than it was at the time.

The interior of the new Clifton Cathedral (Temple Local History Group collection)

WD & HO Wills were building a new £15m state-of-the-art tobacco factory at Hartcliffe and work was due to begin on the massive new West Dock at the Bristol City Council-owned port of Avonmouth. This would become the Royal Portbury Dock, though how many jobs it would create was a moot point now that those newfangled containers were coming in.

Bristol’s tobacco industry was thriving and would soon move to a new state-of-the-art factory in Hartcliffe (Bristol Post)

The expansion of Avonmouth was all the more important because the old City Docks – the floating harbour – in the middle of town were now closed. Less than ten years previously this had still been a busy working area, but now large areas on the waterfront were derelict and overgrown. The future of the floating harbour area was a live issue. Council plans to cover over or fill in parts of the docks, and to build big roads through or over them, were still in play, despite furious lobbying by the Bristol Civic Society, the Clifton & Hotwells Improvement Society, the Inland Waterways Association and others.

Work started on the new West Dock at Portbury (Bristol Post)

By 1973 many councillors who had initially supported the plans were getting cold feet. It was one thing to run dual carriageways through central Bristol, but many were only now realising that those same roads would cut through their own wards, and that their voters were not happy.

Nonetheless, in June’s local elections, Labour increased its majority, taking 56 out of 84 seats and leaving the Conservatives with just 25. Significantly, the same polls saw the election of three Liberals, including a 26-year-old architect named George Ferguson. These were the first Liberals on the council since the party had subsumed its identity into the Citizen Party between the wars. By 1973 the Citizens had long been Tories in all but name.

While the debate over the future of the docks raged, the water was being put to new uses. WD & HO Wills were the sponsors of one of the summer’s big local events, the Embassy Grand Prix powerboat races. The races were expected to turn into an annual event, which they did for a while, despite the Bristol course being one of the most dangerous in the world. In 1973 it claimed the life of German driver Rudi Hersel. He left a wife and two young children.

The 1973 Powerboat Grand Prix (Bristol Post)

The previous weekend the docks had also hosted its third annual Water Festival, entertaining visitors with its array of boats and nautical-flavoured entertainment. This would in later years become the Harbour Regatta, nowadays the Harbour Festival. And of course the event did its bit to demonstrate to everyone how the docks could be a playground and a water feature.

The 1973 Water Festival, nowadays the Harbour Festival (Bristol Post)

The biggest show by far that summer, though, was Bristol 600, an extravagant celebration of Bristol’s six centuries as a county following the granting of the charter by King Edward III in 1373. It was centred on a huge exhibition and arena on the Downs, with jousting and ox-roasts and displays by local firms and voluntary organisations and more.

An episode of Jeux Sans Frontières, the Europe-wide heat of It’s a Knockout, was to be broadcast from the arena. This was a popular TV game show in which teams of amateurs competed in all manner of silly games, often in foam rubber suits for comedic effect (and their own safety), and of course the games in the Bristol show would be medieval-themed. The Queen and Duke of Edinburgh would also be dropping in.

It’s a Knockout from the Bristol 600 arena, and watched by 400 million people Europe-wide (Bristol Post)

It wasn’t just a big knees-up for a round-figured anniversary. It was also driven by a feeling across all the political parties in the city that the 1972 Local Government Act would end centuries of proud civic history. The Act would bring the new county of Avon into being on 1 April 1974, and many feared that Bristol’s status and importance would be downgraded and its identity smothered.

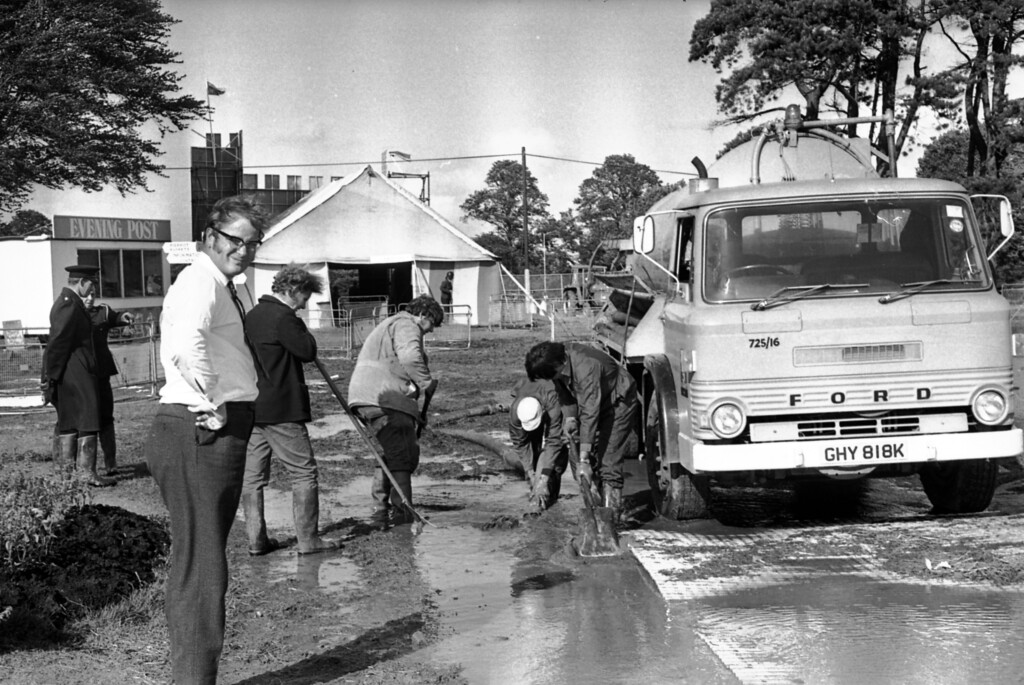

The big three-week show on the Downs was dogged by terrible weather. A tremendous gale blew up, making a mess of the site early on. Heavy rain later churned up the mud even more and the royal visit was cancelled.

Clearing up the Bristol 600 site after a gale (Bristol Post)

Exhibitors mutinied, threatening to walk away, so then it was back on again; Her Majesty spent 20 minutes being driven around the site on the back of a Land Rover. The show ended and, well, despite the weather, it hadn’t been a complete disaster, had it? The international heat of It’s a Knockout had been watched by 400 million people across Europe, so that was a pretty good advertisement for Bristol, wasn’t it? It could have been a lot worse, right?

It got worse. But then everything got worse. In the autumn there was a short war in the Middle East and the OPEC oil-producing cartel squeezed the West’s oil supplies.

When, in 1973 your mum or gran (because women, sorry, ‘housewives’ did all the shopping back then) returned from the shops and complained about the shocking price of everything, inflation was already running at 10 per cent. These things are relative, of course. In early December, comedy duo Mike and Bernie Winters (remember them?) opened the new Fine Fare (remember them?) supermarket at the Broadwalk in Knowle. Here you could get one of those Fray Bentos tinned steak and kidney pies for 22p or a tin of Ye Olde Oak cooked ham for 69p. Wash it down with a bottle of Harvey’s Bristol Cream for £1.34.

At the time, the average UK weekly wage for a man in full-time work was around £41, but it would grow a lot, and not because of prosperity. The rising cost of living summoned corresponding union demands for pay increases to keep pace with the cost of living. The inflation rate would get even higher in the years to come.

Among those taking industrial action by the end of the year were rail workers and coal miners, and the start of 1974 saw Heath’s government introducing a three-day working week to conserve electricity and coal stocks.

Concorde failed to live up to its commercial promise and the bullish predictions for Bristol’s forthcoming good times failed to materialise. In the economic woes of the 1970s many old Bristol firms went under and few large building projects materialised.

Admiring a cutaway model of Concorde at the massive Bristol 600 exhibition on the downs. It was still possible to believe that the supersonic airliner would sell in large numbers. (Bristol Post)

Meanwhile, by the end of the year the Bristol 600 creditors had formed a lengthy queue. It turned out that the firm which had organised the show, Commerce Displays Ltd, had debts of almost £75,000. Think of that as well over half a million nowadays. The Fraud Squad was called in, and Eric Castle, Deputy MD of Commerce Displays, did a runner. At the same time, £17,000 of the show’s gate money disappeared.

He was said to have holed up in what is now Zimbabwe. Back then it was Rhodesia, a pariah state where the post-colonial white minority regime was clinging on to power and from whence extradition was impossible.

Castle was later said to have been killed in a rocket attack by independence fighters, but who knows? Perhaps he faked his death and in doing so became Bristol’s own Lord Lucan.