‘There’s Nothing New Under the Sun’ Julian Baggini

Share this

A long time ago, in what seems like a galaxy far, far away, a much younger version of myself would take his musty wine-red faux-velvet seat in Folkestone’s Curzon Cinema, ready to be immersed in whatever the curtains opened to reveal.

Today when I settle into a much more comfortable chair at Bristol’s Watershed or Everyman it is not only the cinemas that have changed. I see very different kinds of films now because I have in many ways become a very different person.

Yet it seems to me that the continuities are more important than the differences. ‘Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose,’ as the graduate me might now say, and if I used to say ‘there is nothing new under the sun’ instead, it only reinforces the point.

I am that old cliché, the grammar school boy whose education opened a route to the middle class. I grew up with little exposure to what I might then have called high culture. Most of it came in the form of English Literature at school where it now staggers me how little we were taught about art and music. At home, our household’s books seemed largely ornamental, with volumes of the aspirational but mostly unread Encyclopaedia Britannica taking up much more space than all the other books combined. Although my father was a reader and autodidact, he was largely absent. Ours was a home filled with the sounds of Radio Two in the morning and, from the time we got back from school in the afternoon, with whatever was on the television, rubbish or not.

My town, Folkestone, offered some supplements to this thin cultural diet, only partially ingested. The one art gallery was completely off our radar and I never even thought of going to it. I did see my first orchestral concert at the Leas Cliff Hall, but only the one. For the most part it was the scene of numerous memorable rock concerts.

The closest I got to high culture was the Leas Pavilion Theatre, which housed a repertory company. When my father visited, we often used to see whatever was playing. Nine times out of ten it was a whodunnit or a farce, but with the likes of Alan Ayckbourn and J B Priestley in the repertoire, it was a priceless introduction to theatre. Incongruously, they once performed Pinter’s The Birthday Party, which was utterly baffling yet engrossing. However, it closed in 1985, fittingly with a production of Agatha Christie’s An Unexpected Guest.

The most visited cultural venue by some margin was the three-screen Curzon Cinema, as it will always be known to me, despite changing its name to the Cannon at some point. It screened only mainstream fare, and when I try to remember the films I saw there, it is a little dispiriting to find that there are so few I’d relish seeing again. For nostalgia I’d sit through Flashdance (1983) and for curiosity The Dark Crystal (1982) but not much else. These were the years of the worst Bond films, Octopussy (1983) and A View to a Kill (1985); crowd-pleasing comedies such as Beverly Hills Cop (1984) and Crocodile Dundee (1986); the big-budget adventures of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). I remember the technically ground-breaking but dull sci-fi hit Tron (1982), the disappointing Dune (1984), the Cold War teen drama War Games (1983), the pure entertainment of Back to the Future (1985), as well as the unadulterated dross of Police Academy (1984) and The Goonies (1985).

If I were looking for evidence of precocious or idiosyncratic tastes, history would not provide me with any. Indeed, my soft spot for Disney took me to the Curzon not only for The Rescuers (1977) when I was still respectably under ten, but also as a should-have-been-too-cool teenager to see The Fox and the Hound (1981) and as a sixth-former to The Black Cauldron (1985). The only hint of originality is that I failed to be caught up in the manias for Star Wars (1977), Grease (1978) and ET (1982) which in the days before advanced booking saw queues round the block. The only time I would stand in line was on Mondays, after they made it the cheap ticket night. I did see all three once things had calmed down, but at least I never have seen Top Gun (1986).

Yet my years in the tatty stalls were a kind of apprenticeship for years of cinema-going to come. My tastes may have been primitive, but I always went along for the films, which is not something that can be taken for granted. I remember going to a Saturday morning ‘juniors’ club, but only once or twice because I couldn’t stand all the raucous shouting and mayhem, which was, of course, precisely what most of my peers loved the most.

As I got older, if I went to the cinema with a girlfriend it was not to snog on the back row. I still remember being annoyed by the teenagers rolling around shouting ‘fucking ‘ell!’ in hysterical laughter at the smutty oral sex scene in Police Academy. They were hardly disturbing my viewing of a masterpiece, but still: the film was always the thing, even if the thing was crap. It is telling that although I can remember many of the films I saw, I rarely recall who I saw them with.

And then one day I saw a film that changed my cinematic life: Woody Allen’s Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Here was a film the likes of which I had never seen. No action, no adventure, no soundtrack-powered tension-building, no hero’s journey. But it was philosophical, intelligent, brilliantly acted, both funny and serious. It was as though I had finally discovered what an adult movie looked like and, no, it wasn’t full of X-rated sex. Was this what they meant by art house cinema?

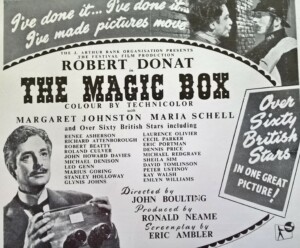

If that makes me sound naive that’s because I was. My film-viewing life had been extremely sheltered. The most unusual films I had seen to date had been Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti westerns on the television. The only other vaguely unconventional film I can remember seeing was The Snake Pit (1948), which seemed at the time to be a remarkably vivid exploration of madness (since no one would have said ‘mental illness’ at the time). Of course, I had seen films that I would still consider classics, but all conformed to the conventions of the epic, biopic, adventure, war film, comedy and so on.

Hannah and Her Sisters did not transform my viewing habits overnight. Some people like me respond to their cinematic epiphanies with the zeal of the convert, rejecting all the ‘trash’ they used to love and desperately watching as much ‘serious’ stuff as they can. I didn’t. Even if I had been keen to devour the entire oeuvre of Ingmar Bergman, I doubt my local video shop would have stocked any of his films and we didn’t have a VCR anyway. I remained a viewer of mainstream films, just one whose tastes had moved along the spectrum towards the more serious. I went on to become an avid reader of the film magazine Empire when it launched in 1989, not a subscriber to the highbrow Sight and Sound.

But the studio films I eagerly went to see became increasingly more serious, often directed by auteurs. In 1987 I would have seen Brian De Palma’s The Untouchables, Oliver Stone’s Wall Street and David Jones’ 84 Charing Cross Road; in 1988 Lawrence Kasdan’s The Accidental Tourist, Jonathan Kaplan’s The Accused, Terry Gilliam’s The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons, Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning. Even at university in Reading, there were few chances to see anything really different, except at the fortnightly film club where Peter Greenaway’s The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover (1989) widened my horizons further. (Note – with horror – how all these directors were white men.)

Slowly, between now and then, my tastes evolved. Now if I go to the cinema, it’s more likely than not that the film will have subtitles. There is little I want to see at the descendants of the three-screen Curzon: the huge multiplexes with their huge popcorn tubs and fizzy-drink cups. Yet we are our histories, including our cultural ones. For instance, although my musical tastes have widened enormously, most of what moves me most is still rock of the late Seventies and Eighties. Nor have I ever entirely made up for all the culture I missed out on in my first 18 or so years. In some ways I have come a long way from a declining English 1980s seaside town, but I will never have the polish and accomplishment of those who grew up steeped in arts and culture.

That’s OK. It’s what I am. Like many who were the first in their family to go to university, my roots still show through. Although I loathe the inverted snobbery that would make me proud of them, I am certainly not ashamed of them. But whereas some cultural progressions are difficult to make if you leave it too long, cinema is at least more accommodating to late developers. I don’t feel ignorant about film in the same way as I do about music or art. It’s not that I have a lot of knowledge, but I feel I understand enough about film to appreciate properly what I am seeing. And that, I think, says more about the democratic nature of film than it does about me.

There have been no opportunities to wallow in nostalgia at the Curzon. The year after I left home for university it closed due to structural problems and was demolished with indecent haste. If it were still open, I doubt many films it showed would attract me. But were I to drop in, perhaps to see the latest Bond, I would feel at home, at ease, in a place where I belonged. The old cliché is that you can take the boy out of the town, but you can’t take the town out of the boy. The same is true of our cultural homelands. My eyes have widened but they remain the same eyes that were shaped by a childhood of Hollywood, B-movies, cans of Cresta and tubs of interval ice-cream.

Julian Baggini is a writer and philosopher whose books include The Ego Trick, Welcome to Everytown, How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy, The Godless Gospel and The Great Guide: What David Hume Can Teach Us about Being Human and Living Well. He writes for several newspapers and magazines, was the co-founder of The Philosophers’ Magazine and is Academic Director of The Royal Institute of Philosophy.