The Universality of Orwell’s Message James Bloodworth

Share this

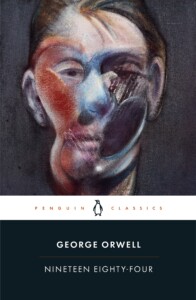

Nineteen Eighty-Four was the most terrifying book I read as a child.

There were other books that ought to have been more frightening – War of the Worlds and Lord of the Flies are just two examples – but the sheer bleakness of Nineteen Eight-Four left a more lasting impression.

As with Franz Kafka’s The Trial, the impact of Nineteen Eighty-Four is in the fact that there is no way out. ‘If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face – forever,’ the Inner Party apparatchik O’Brien informs Winston Smith, the book’s doomed protagonist.

Published in 1949, Nineteen Eighty-Four has since found itself deployed in the service of half-baked conspiracy theories around everything from close circuit television to political correctness to the election of American President Donald Trump. Indeed, is there anything more tedious than the person wielding the freshly thumbed copy of Nineteen Eighty-Four who concludes that we are ‘already living it!’?

This is in a sense a testament to both the potency of the novel and the accessibility of Orwell’s prose. As DJ Taylor, an Orwell biographer writes, Orwell creates ‘the feeling [in the reader] that, as he put it about Henry Miller: ‘He knows about me. He wrote this for me’. This impression is strongest in Orwell’s first-person essays. But it comes across in his fiction too.

Nineteen Eighty-Four is a book about power and its corrupting effect on human society. Originally entitled The Last Man in Europe, the book’s protagonist, Winton Smith, is a solitary figure entrapped by a political system that seeks to utterly bend reality to its will. As for individual heretics such as Winston? ‘Posterity will never hear of you. You will be lifted clean out of the stream of history,’ as O’Brien puts it.

Many on the political right interpret Nineteen Eighty-Four as a treatise against socialism. And it must be said, Orwell makes this rather easy at times. The ruling party in Airstrip One is called IngSoc, shorthand for English Socialism. The cult of state power is the supreme value in Airstrip One, as it was for Lenin and the Bolsheviks. To paraphrase the Polish philosopher Leszek Kolakowski’s judgement on Leninism, there is very little in Nineteen Eighty-Four that could not be justified on communist principles.

This is quite a sweeping statement and I should probably unpack it a bit.

Much of what transpires in Nineteen Eighty-Four can be traced back to O’Brien’s statement to Winston that in Airstrip One, ‘There will be no loyalty, except loyalty to the party’. Certain things follow from this, such as the destruction of civil society, which was a hallmark of communist rule during the twentieth century. ‘Within the Revolution, everything. Against the Revolution, nothing,’ as Fidel Castro famously said in 1961. ‘Humanity is the Party. The others are outside – irrelevant,’ as O’Brien puts it in the novel.

But Airstrip One goes much further than communism ever realistically imagined that it could. ‘We have cut the links between child and parent, and between man and man, and between man and woman,’ O’Brien tells Winston. He adds that the ‘sex instinct will be eradicated’. Winston later remarks on the ‘direct, intimate connection between chastity and political orthodoxy’.

It is worth emphasising this final point. As well as being a work of dystopian fiction, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a love story. The protagonist Winston Smith falls head over heels for Julia, a propagandist for the Junior Anti-Sex League, and a good portion of the book is given over to their surreptitious sexual relationship. Surreptitious because Big Brother understands perfectly well how subversive sex – or more specifically, the ‘sex impulse’, as Orwell puts it – can be; it is another potential forum in which rival loyalties are created. This is dangerous, for in Airstrip One Big Brother should be the only focus point for love and reverence.

Much of Nineteen Eighty-Four’s bleakness derives from its setting in bombed out post-war London. The juxtaposition of poverty and squalor – ‘vistas of rotting nineteenth-century houses, their sides shored up with baulks of timber’ – with the high-tech tools of repression creates simultaneous feelings of familiarity and revulsion that bring to mind the concept of the so-called Uncanny Valley. It is also what gives the book more power than comparable dystopias such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, the latter of which inspired Orwell’s masterpiece.

As with Orwell’s writing more broadly, Nineteen Eighty-Four is contradictory at times. ‘Men are infinitely malleable,’ says O’Brien to Winston as the latter is undergoing political rehabilitation by torture. Yet earlier in the book, O’Brien had talked of a never-ending struggle against heresy. ‘The heretic, the enemy of society, will always be there. So that he can be defeated and humiliated over again,’ O’Brien says.

Yet the struggle against heresy continues precisely because man is not infinitely malleable. If he were then it is inconceivable that there could be a Winston Smith or a Julia in Airstrip One. Rebellion exists because there is something in human nature that is thwarted by the state, or in this case Big Brother.

Winston grasps this which is why he places such hope in ‘the proles’. ‘In the end their awakening would come,’ reflects Winston as he watches a working class woman hanging up washing in a grimy backyard. ‘And until that happened, though it might be a thousand years, they would stay alive against all the odds, like birds, passing on from body to body the vitality which the party did not share and could not kill.’

Whether one views Nineteen Eighty-Four as an optimistic book or a work that, as the cultural critic Raymond Williams put it, ‘created the conditions for defeat and despair’, largely rests on whether one places one’s faith in the working class or accepts the formulations of O’Brien, who dismisses them as ‘helpless, like the animals’.

Orwell’s great gift was to understand all of this as an outsider. He had experienced a taste of the murderous paranoia of Stalinism in Spain during the civil war, where the Soviet Union suffocated the revolution and would almost certainly have murdered Orwell had they captured him. Yet Orwell’s depiction of life under a police state is remarkable for someone who had not himself lived under such a regime. As the Polish dissident and essayist Czeslaw Milosz put it: ‘Even those who know Orwell only by hearsay are amazed that a writer who never lived in Russia should have so keen a perception into its life.’

There are places today where one can still see glimpses of the world depicted in Nineteen Eighty-Four. The most obvious example would be North Korea, where the late journalist and essayist Christopher Hitchens noted that it was as if the Kims ‘got hold of an early copy of the novel and used it as a blueprint’.

A decade ago I lived for a while in Cuba, and while the Castroist system was less heavy-handed than many of its Stalinist counterparts, a version of the Big Brother state extended its tentacles into every aspect of life. Huge posters bearing the face of Fidel Castro exhorted the Cuban people to trust the benevolence of the heroic leader; state newspapers celebrated the surpassing of production quotas while everything around was crumbling; your every move was monitored by zealous party activists who formed part of the ‘Committees for the Defence of the Revolution’.

Most revolutions may begin with egalitarian aims, however they usually morph into a desire to hold onto power. As Albert Camus put it, ‘The slave begins by demanding justice and ends wanting to wear a crown’. Or as O’Brien phrases it, ‘One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship’.

It has been said, perhaps most prominently by the media theorist Neil Postman, that Huxley’s dystopian novel Brave New World is a closer representation of society today than Nineteen Eighty-Four. This is undoubtedly true (or to a point at least: our society is still really nothing like life in Huxley’s world state). Yet the popularity of Orwell’s book exceeds that of Brave New World – not to mention the ubiquity of Orwellian terms in popular culture: Thought Crime (O’Brien: ‘A Party member is required to have not only the right opinions, but the right instincts.’), Big Brother, War is Peace – because it more acutely captures the tension between freedom and security.

Totalitarian ideologies like communism and fascism – or in Airstrip One, a blend of the two called ‘oligarchical collectivism’ – purport to have solved this riddle in favour of security. As O’Brien informs Winston, ‘Slavery is freedom. Alone – free – the human being is doomed to die… But if he can merge himself into the Party so that he is the Party, then he is all-powerful and immortal’.

Yet as Orwell recognised, there is such a thing as objective truth, which will ultimately bring down systems built on a foundation of lies, even if such systems are able to crush individual dissenters like Winston along the way. Like Marx and Orwell himself, Winston puts his faith in the decency of the proles, who are both more numerous than the intellectuals and are ‘human beings’, as he tells Julia as if stumbling upon something profound and revelatory.

Perhaps paradoxically considering his faith in the masses, Nineteen Eighty-Four is also an assertion of individuality in a world that is trying to suffocate independent thought. ‘There was truth and there was untruth, and if you clung to the truth even against the whole world, you were not mad,’ Winston reflects.

At a time when majoritarianism is increasingly conflated with democracy, this is a principle worth holding onto. I suspect it’s also what attracts so many adolescent readers to the book year after year, generation after generation.