The Soul of the City: A Personal View

Share this

I arrived in Bristol the week that Arnolfini moved to its present location on Narrow Quay. It was October 1975 and Bristol was on the cusp of change. Arnolfini stood in an empty harbour landscape. Apart from a sand dredger berthed in Bathurst Basin, the docks were deserted and eerily quiet. As I sipped my lapsang souchong tea – this was in the days before flat whites – Bristol felt different. I liked the West Country feel. The florid faces in cider pubs; the gentle accent; the jazz in King Street. For me, brought up in the Home Counties, the West meant one thing – holidays.

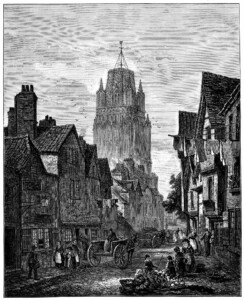

I did what every newcomer to Bristol should do. I climbed the 108 steps to the top of Cabot Tower, which had been erected in 1897 to mark the 400th anniversary of Cabot’s pioneering voyage to North America. The rolling topography of Bristol is spread below the tower. To the west, Clifton’s Georgian terraces are stacked up the hillside. Then there’s a glimpse of Brunel’s Suspension Bridge, while the flag-clad masts of the ss Great Britain poke up from the docks. There’s the cathedral and the elegant spire of St Mary Redcliffe. You can make out the tower blocks of Hartcliffe, huddling below the Dundry slopes and the landmark Dundry church tower. The 1930s estate of Knowle West is tucked over the ridge. The north of the city is largely obscured by the steep drama of St Michael’s Hill.

The 1970s was a time of rising unemployment. I wasn’t sure what I could do with my sociology degree. There was one place I reckoned I could get a job: the dole office in Nelson Street. It was a sharp introduction to Bristol at its rawest, and was to be the setting for my book Where’s My Money? (2016). Where’s My Money? is fiction – I have to say this as I’d signed the Official Secrets Act.Working in the dole office was a good way to discover the less celebrated side of Bristol. I met shifters, grifters and the early morning snifters. But mostly it was hard-working people down on their luck.

Several years later, when I was dating Maggie, my future wife, she was alarmed by how many street drinkers knew me.

I quickly got to discover the city. It wasn’t London. It didn’t feel like London, it didn’t look to London. Bristol has been called the capital of the South West. I’m not so sure about that. I don’t think a Cornish person would see it that way. Nevertheless, Bristol has traditionally looked westwards, away from the capital.

Historically, Bristol owes its existence to its harbour. At first sight, the twisting Avon, with its ferocious tidal range, is a strange location for a port. But it was safe. There would never be a surprise attack on Bristol by water.

During medieval times there was significant trade with Ireland and even Iceland. And then came trade with North America. Few were surprised in 1497 when John Cabot came across a supposedly new continent – new to Europeans, at least. Canny Bristolians knew of a faraway land with a cod-rich sea well before Cabot’s voyage.

Today the docks are quiet. Commercial shipping has moved to easier moorings at the mouth of the Avon. But Bristol’s past links with the sea are still in evidence. Waterside warehouses have been repurposed for arts centres, cafés, nightclubs and museums. The sculptural cranes are heritage pieces. Even the Underfall Yard with its sluices, vital for the regulation of the water level of the harbour, is a working museum. Sadly, it has recently suffered a devastating fire. Rather than taking labourers to work, ferries now scoot tourists across the harbour. The docks may well have closed for commercial trade, but the harbour remains an unmistakable emblem of Bristol. On a warm summer’s evening there are few better places to be.

Bristol’s motto is Virtute et Industria – virtue and industry. Industria maybe, but virtute, certainly not. If we understand virtue to mean ‘high moral standards’, over the years Bristol’s merchants have fallen tragically short. The transatlantic trade in enslaved people that dominated Bristol’s commerce for over 150 years gave the city great wealth. But at what human cost? Between 1698 and 1807 it is estimated that over half a million kidnapped Africans were transported by Bristol’s ships. The barbarity of this enterprise is almost too horrendous to countenance. It is history that cannot be ignored and is currently being unearthed and rewritten. Directly or indirectly the effects of slavery are all pervading.

Bristol is said to be a city of protest; Bristolians demand to be listened to. In The Bristol Guide, printed and published by Joseph Mathews in the early 1800s, it is written that ‘the populace are apt to collect in mobs on the slightest and most frivolous occasions’. But riots aren’t the only way of showing discontent. In the 1960s, Bristol Omnibus Company, jointly administered by Bristol City Council, operated a blatant colour bar. The Bristol Bus Boycott in 1963 influenced the passing of Britain’s first Race Relations Act two years later.

It was a proud moment when Bristol hit the world news in June 2020. A statue of Edward Colston, a Bristol-born slave trader, was pulled down, rolled along the waterfront and dumped into the docks. For several years there had been discussions regarding the text of a plaque to explain the origins of Colston’s wealth. But little had happened. Wording was agreed and rejected. Eventually, during a Black Lives Matter protest, the demonstrators took things into their own hands.

Rescued from its watery grave, for a while the Colston statue, splattered with red paint, lay recumbent on display in M Shed museum. While it is no longer on show, the statue can be viewed on M Shed behind-the-scenes tours.

You can’t help but notice that Bristol is a youthful city. With two universities and a student population of over 40,000 there’s a constant flow of new talent to support Bristol’s world-class creative industries. There’s a myth that Bristol is laid back. Don’t be fooled. Bristol may not be a city of sharp suits and overly aggressive businesspeople but there’s a heroic energy to the place.

Concorde, the BBC Studios Natural History Unit and bad-boy-turned-saviour Banksy are internationally known. We have Paul Dirac to thank for Quantum Physics and, at the other end of the spectrum, who doesn’t love Wallace and Gromit? I could go on. For a city of just under half a million people Bristol punches well above its weight.

However, as I saw when I worked in the dole office, there is darker side to the city. In 2017, drawing on data from the 2001 and 2011 censuses, the Runnymede Trust produced a report (Bristol: A City Divided?) that revealed Bristol to be more unequal than most other UK cities. Far from being a melting pot of diversity and multiculturalism the report found that Bristol’s Black and Minority Ethnic communities had poorer job prospects, worse health and fewer academic qualifications than those in the white communities. What the report didn’t mention is that there are white communities in Bristol that are also living in areas of deprivation. Bristol has a problem. Positive action is required.

One last thing. Here’s a question you should never ask in Bristol. ‘How do I get to…?’ Even before the current Clean Air Zone restrictions, this is a query that strikes dread in the hearts of Bristolians. Bristol has grown organically, there’s no grand planning, no grids of streets. The city is sliced not only by the Avon but also The Cut. Then there are the vertiginous hills. Bristol has some of the steepest residential streets in the UK. There is no direct route anywhere. The quickest way to get from A to B is open to constant debate. Don’t bother with sat nav – it has no idea, either.

I’ve lived in Bristol for nearly 50 years and I still feel I’m on holiday. I continue to explore the city, finding new corners, new streets, new communities, even. There’s a vitality to the city and always something new to try. Want late night music? Try the grimy buzz of Stokes Croft. Looking for off-the-wall art? Go to the fabulously bohemian annual Totterdown Arts Trail (other arts trails are available). Searching for exotic food? Visit the multicultural St Mark’s Road, Easton. Keen to see epic street art? Make your way to North Street, Bedminster. And when you’re tired of all that you can take an energising stroll in one of Bristol’s many attractive parks and marvel (sometimes) at the hot air balloons floating overhead.

My career has been Bristol-based and, with my wife, I’ve brought up two children in the city. With its enterprising, creative and free-thinking people and its unique geography, I can’t think of a better place to have done this.

Michael Manson was a co-editor of the Bristol Review of Books (2006-13), a co-founder of the Bristol Short Story Prize (2008) and an organiser of the Bristol Festival of Literature (2010-2020).

This article appears in Bristol 650: Essays on the Future of Bristol, a book bringing together essays from over 30 contributors, addressing some of the challenges the city faces and sharing ideas about how we might meet them. From dealing with the past, the future of social care, culture and housing to building a city of aspiration, the book looks to promote learning about the future of Bristol and encourage new ideas to come forward.

Free copies of Bristol 650: Essays on the Future of Bristol will be available at selected Festival of the Future City events in October 2023, or you can find articles featured in the book at bristolideas.co.uk/bristol650book.