Taking to The Open Road Peter Domankiewicz

Share this

A jumble of junk: that seemed to be more or less the view held by the National Film and Television Archive in 1994 of the material they held from The Open Road. And anyway, it bore the Friese-Greene surname, which was regarded as the hallmark of all that was dubious.

But to me, the idea of a travelogue of Britain shot in colour in the mid-1920s (when there was little colour filming) seemed to be of clear interest. I was fortunate in that I encountered Luke McKernan there, who would become a prominent authority on early British cinema and is now Lead Curator of News and Moving Image at the British Library. He took an interest and got digging, eventually handing over a pile of copies of paper records, some typed, most handwritten, with shot lists.

It really was a lot of material, covering large swathes of Great Britain, originally intended to be a 26-part series of shorts stretching from Land’s End to John O’Groats. But it was all out of logical sequence, with intertitles clumped together, and the accepted view was that the project had probably never come to fruition, nor been screened, and this was all that remained. I managed to arrange to show a couple of reels, that had been duplicated, at the Bath Film Festival in 1996, and proposed to the head of the Archive that there was a great TV series to be made from it. That idea aroused zero interest.

In the years that have passed since then, attitudes have changed entirely about its value, and we know more about its original distribution. We have seen sections in The Lost World of Friese-Greene on the BBC, the BFI National Archive has lovingly restored it, clips regularly do the rounds on social media, and on 1 August 2021 we can have the pleasure of seeing it projected in a cinema with expert musical accompaniment.

The whole project was the work of Claude Friese-Greene, William’s eldest son and the one who followed most closely in his father’s footsteps. He began his film career early. In 1912, at age 14, with the family then living in Brighton, he would shoot simple two-reelers, loading the camera, filming, then developing and printing the ‘rushes’, ‘with an assistant even younger than myself,’ so he said.

His father had been working on a variety of possible colour systems for moving pictures from around the turn of the century, with varying degrees of success. These worked principally by showing a red frame followed by a blue/green frame rapidly enough that the eye and brain merged them into a decent semblance of life in colour, a principle duplicated in the Kinemacolor system. Claude recalled being taken out of school one day as a child to appear in an early test film and, at just 16, Claude too applied for a patent for coloured moving pictures and set up the Aurora Film Company, which had a capital of £5,000 and a plan to make movies in colour. Then war intervened.

William Friese-Greene died on 5 May 1921. Extraordinarily, he was posthumously granted at least five patents relating to colour filmmaking – in Britain, the USA and Canada – such was his prodigious level of invention right to the last. Later that same year, Claude was at the patent office too with what he considered to be a significant improvement on his father’s ideas – significant enough to patent in several countries.

When the time came to try out his new system in front of an audience, he was very specific in his choice of location. In tribute to his recently deceased father, he decided to do it in William’s home city of Bristol. The date was Wednesday 5 April 1922, and the place was the Picture House, a 470-seater cinema that used to occupy 9 to 11 Clare Street. The audience were invitees, including the Lord Mayor and Lady Mayoress, a large number of city councillors and sundry ‘prominent citizens’.

During the Great War, Claude had been drafted into the Royal Flying Corps. After the war he had set up in business with an army pal, Roland Humphery under the name ‘Humfriese Productions’, undertaking aerial photography and shooting a series of black-and-white one-reelers, The Beauty of Britain. This Bristol screening was part of their ongoing collaboration. According to a film trade publication, ‘Some interesting scenics were shown, including a trip across England by aeroplane, with some beautiful colour effects. A wide range of subjects were shown including old-fashioned and highly-coloured costumes, close-ups of faces with delicate flesh tints, colour dropped into a bowl of water and many other subjects.’

The guest of honour clearly thought he needed to give a personal endorsement, and ‘At the end of the demonstration the Lord Mayor expressed himself satisfied with the show that had been given. He thought that the films were excellent and pointed out that he had once upon a time had some experience of photography, so that he was not judging the films purely from the point of view of a novice.’ That said, it seems the novices were impressed too.

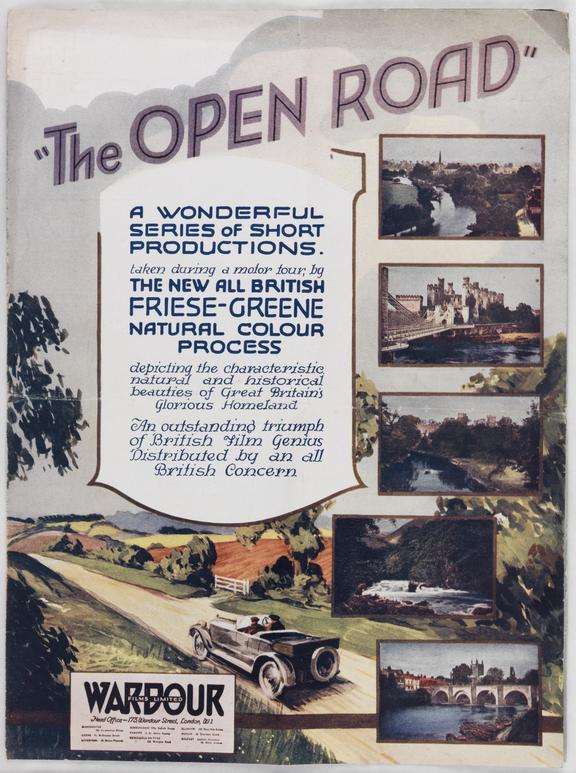

Encouraged, Claude went away, improved the system further and at the end of the following year declared a new process and production company under the name ‘Spectrum Films’, going on to shoot some well-staged short films in a studio, which he even took to New York to catch the attention of the US trade. In 1925 he struck a deal with Wardour Films in London to shoot a series of travelogues covering the length of Britain in colour, which was to be called ‘The Open Road’. And he took to that road in July to start shooting, a process that would continue into the next year, when the films were already hitting the screens.

A trade screening at the London Pavilion, accompanied by a full, front-page ad in The Bioscope, complete with glowing review, announced the arrival of the series. And if you’d happened along to The Palace cinema in Bristol at the start of May 1926, probably to catch Jackie Coogan in his new ‘screamingly funny’ film, Old Clothes, you would also have had the pleasure of seeing Devon and Cornwall depicted in ‘Spectrum Colour’ in the first instalment of The Open Road.

The first time that footage will have been screened in a Bristol cinema again, 95 years down the line, will be at 3.30pm on Sunday 1 August, along with a wealth of other colourful sights of Britain in the 1920s and the masterful accompaniment of Neil Brand. It’s a trip you should take.