Rene Clair’s Le Silence est d’or: An Introduction Bryony Dixon

Share this

This is a transcript of the introduction to the screening of Le Silence est d'or which took place on 28 October 2021 as part of the Early Cinema Pioneers season.

Rene Clair was one of a generation of very bright filmmakers like Lubitsch and Hitchcock and Howard hawks who straddled the silent and sound eras. Rene Clair excelled at both.

Clair particularly loved the exuberance and promise of the earliest days of film – it is this era he revisits in Le Silence est d’or / Silence is Golden, a world he knew as a boy. He was born in 1898 in Paris and acted in several late Feuillade silent serials. He also loved the experimentation so characteristic of the 1920s. Most students of cinema these days in fact will know him best for Entr’acte (1925), the Dadaist comedy, made with Erik Satie and Francis Picabia, commissioned as an interlude in an avant-garde ballet. But though he was interested in the film essay, he preferred to make popular films; he wanted to be up there with Chaplin, Stroheim and Eisenstein; ‘they were not working for cine-clubs.’

Having dazzled audiences with his first feature, the magical Paris qui dort (1925) Clair struck gold with a pair of silent film farces – The Italian Straw Hat (1928) and Les Deux Timides – just at the time his precious world of silent film was being threatened by the arrival of the talkies. Like Hitchcock he saw the changes coming and with Deux Timides he set out to put the late silent film through its paces, with a demonstration of visual storytelling that could only be done in silent film.

He decried the commercial juggernaut of sound film in an article, ‘The Art of Sound’ written in London in 1929:

‘. . . the screen has lost more than it has gained. It has conquered the world of voices, but it has lost the world of dreams. I have observed people leaving the cinema after seeing a talking film. They might have been leaving a music hall, for they showed no sign of the delightful numbness, which used to overcome us after a passage through the silent land of pure images. . .’

But then he became intrigued by the technical possibilities of sound film. He saw Broadway Melody (1929) and realised how the American film-makers were moving on from just matching sounds to images:

‘Its makers have worked with the precision of engineers. . . For instance, we hear the noise of a door being slammed and a car driving off while we are shown Bessie Love’s anguished face watching from a window the departure, which we do not see. This short scene in which the whole effect is concentrated on the actress’s face, and which the silent cinema would have had to break up in several visual fragments, owes its excellence to the “unity of place” achieved through sound.’

Clair then went on to write and direct three films – Sous les Toits de Paris (1930), Le Million (1930) and À nous la Liberté! (1931) – that famously made clever use of non-diegetic sound without sacrificing his elegant filmmaking style.

Years later after the trauma of the war, Clair returned to France and made Le Silence est d’or, full of nostalgia for his beloved pre-war Paris. It’s a more conventional studio movie than Clair’s earlier French films. Starring Maurice Chevalier, it focuses on a love triangle (older man, ingénue actress, young actor) loosely inspired by Moliere’s School for Wives, but is set in a ‘factory of dreams’ in 1906 Paris. It doesn’t overwork the world of silent film. It’s a setting, as he said himself, as much as the idealised Paris created by Leon Barsacq’s fabulous sets in which the action takes place.

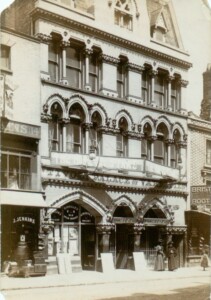

Having said that, Clair’s depiction of the world in which the young film business was beginning to spread its wings is enchanting. We first encounter it at a fairground film-show – a desultory suburban version, in which the characters only go in to shelter from the rain – but for the film enthusiast who has tried to imagine what a Bioscope tent might have been like this must be very close; with its ‘barker’ to encourage the audience inside and the ornate frontage, its bench seats, cranking projectionist, roll-down screen, lecturer and lady pianist.

Then we get to see inside the silent film studio, run by Maurice Chevalier’s character, Emile. He thinks he’s like a Hollywood mogul but in fact he’s a pushover for the terminally idle crew, his permanently depressed leading man and the needy ingénue with whom he falls in love despite having had an affair with her mother (!). The sets and improvised working methods lovingly recreate the anarchic Pathé films from the 1900s that were made in the Joinville-le-Pont studio; Arabian fantasies, melodramas, fairy pantomimes and chase comedies. (My favourite detail is a huge prop spoon – presumably from a pantomime story about a giant’s kitchen – leaning casually against a dressing room wall, eliciting no comment whatever). It allows us to visualise how the early filmmaking world worked and absorb that effortlessly – that’s pretty clever stuff.