Diversity and Representation Does Having a Mayoral System Make a Difference?, by Natasha Carver

Share this

Natasha Carver is a lecturer in International Criminology at the School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol. She is also a member of the specialist research institute Migration Mobilities Bristol. Carver wrote the 2012 report “The Right Man for Bristol?” Gender Representation and the Mayor of Bristol.

The article is part of Bristol Ideas’ Referendum 2022 debate which looks at all aspects of city governance as part of ongoing work on democracy and the forthcoming May 2022 referendum.

Ten years ago, in the run up to the first mayoral election, Bristol Fawcett Society produced a report which documented shocking levels of representational inequality across political leadership in the city (“The Right Man for Bristol?” Gender, Representation and the Mayor of Bristol). A pitiful 17 (24 per cent) of the 70 members of Bristol Council were female, significantly worse than the national average in local government, which itself was a poor reflection of the population. Ethnic diversity was limited to just three (four per cent) Asian-heritage councillors, despite the census returns showing 13.5 per cent in the city identifying as non-white, many of them as African-Caribbean, Black British or African. Voter turnout records showed that those from wealthier neighbourhoods were twice as likely to vote than those from the more deprived areas. In the public and private sectors things were no better, in fact they were considerably worse. Not only were the vast majority of public-sector organisations and private-sector employers led by white men, but so too their boards: ten of the largest employers in Bristol had boards comprised entirely of men.

Bristol lagged woefully behind the national picture: its claim to be a diverse, progressive city was entirely undermined by the cabal of wealthy white men who held power and seemed unwilling to make space for others – even when it came to statues of slave traders.

But that was ten years ago. As we all know, the people of the city took it into their own hands to put the statue where it belonged. And while we debate what if anything should be put up in its place, change has already taken place in City Hall: the number of female councillors has risen from 17 to 32 (46 per cent); the number of ethnic minority councillors (excluding white minorities) from three to nine (13 per cent), not including the mayor himself.

But does this success story have anything to do with the post of the elected mayor? Both mayors have been male in accordance with the script across England and Wales, where it seems people continue to think that they must find ‘the Right Man’ for the job – or as the former Prime Minister David Cameron put it when he inaugurated the mayoral system, ‘our dream is to have real heavyweight, influential figures [like] Boris’ (laugh or cry quietly into your cup of tea over that one).

However, it was George Ferguson who signed the European Charter for Equality of women and men in local life on behalf of the city, and Marvin Rees who launched a Commission for Race Equality (CRE). The former led to the founding of the Bristol Women’s Commission (BWC) which made increasing women’s participation in public life one of their top priorities, while the latter broadened the reach through the Stepping Up programme aimed at increasing diversity in senior leadership across the public and private sectors.

The work of BWC and the CRE has made an enormous difference, but it also requires those who hold power to accept that things need to change.

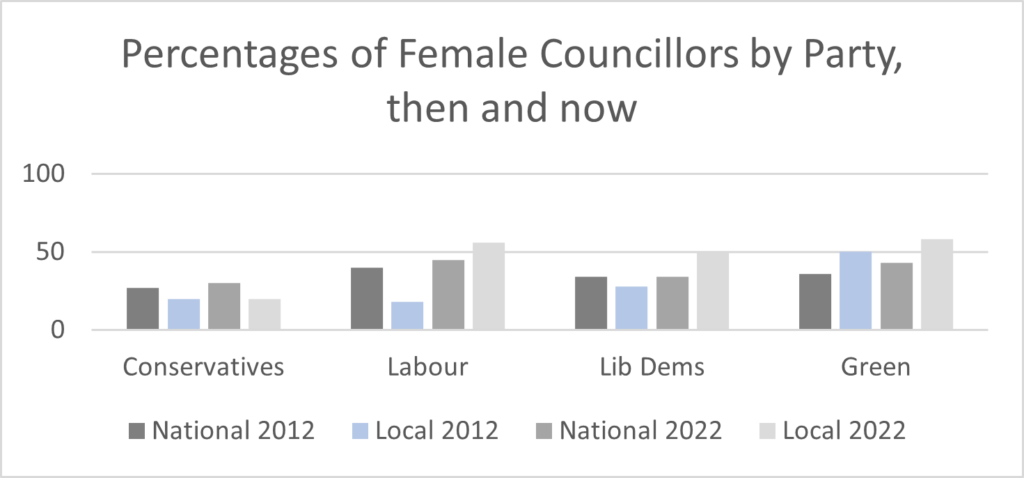

Back in 2012, we reported that despite achievements nationally, men were staunchly over-represented among Labour and Liberal Democrat party councillors in Bristol; the level of female councillors for the Conservative Party was lower than the low national figures; and only the Greens, who had just two councillors, were bucking the trend. In our report we argued that ‘the three main political parties of Bristol City Council are all under-performing in relation to equality and diversity and it is incumbent on them to consider strategies and means for improvement.’

The national picture has not changed. In 2019, the Fawcett Society published research which showed that women’s representation in local government was ‘at a standstill’: just 35 per cent of councillors were female, and progress in this area has been so slow that in 2021 the Fawcett Society calculated that it would take until 2077 to reach gender equality.

But in Bristol, following the admirable efforts of BWC, the Labour Party and the Liberal Democrat Party took these criticisms on board and put women and ethnic minority candidates in seats where they actually stood a chance of winning. The Conservatives, meanwhile, continue to operate as though they are living in the 1890s (when the statue of Colston was erected).

Would there have been real change if the post of the mayor hadn’t existed? It seems unlikely, with all the political wrangling needed to bring about change in a council system. But then if the mayor had been Conservative then it seems even less likely that his cabinet would look remotely like the current one.

The extent to which this is a lasting change and will survive either a change of mayor or the end of the mayoral system is, however, dependent not on how you cast your vote in the referendum, but on changing the way politics is financed, organised and conducted. We argued in 2012 that the three factors which limited diversity in public office were caring responsibilities, cash and culture. With regard to the first two of these – as the BWC have recently documented through a survey of female councillors leaving office (some after just one term) – it costs time and money to campaign for office, things that women and ethnic minority people are still often short of in comparison to white men.

More problematic, however, is the culture of politics. Based on analysis of data from 2015-18, Local Government Chronicle found that formal grievances involving bullying and harassment by council staff had increased by 7.5 per cent. Bristol Council was among the worst with 40 complaints over the three-year period. Despite efforts to change this culture, complaints about what the former Leader of the Greens, Ani Stafford-Townsend, called ‘nasty and bullying sexism’ continue to be made.

In addition to the internal masculinist culture, women and ethnic minority people in public life are increasingly subject to misogyny and race hate on social media. This has been found to be the major factor preventing women from taking up roles in public life and driving out those who already have public roles. It’s hard not to see social media as an amplified echo chamber of the sexist culture of politics. A ‘heavyweight’ may have been the stereotype of ‘the right man’ for the job in 2012, but the era of the dinosaurs is over. If we stick with the mayoral system, then perhaps this time we can think about choosing the right person for the job.

Find out more about Bristol Ideas’ Referendum 2022 debate. Copyright of articles remains with the authors.