Opening The Magic Box Christopher Frayling

Share this

Amongst the many plaques in Bath commemorating the great and the good from Georgian and Victorian times, which adorn the houses where they lived and worked (or sometimes merely slept), there is only one which points towards the popular culture of modern times.

It is just off New Bond Street in the corridor at the bottom of Milsom Street. It isn’t one of the pucca bronze plaques with scrolls – so it isn’t quite in the premier division – but by way of compensation it does contain an unusual number of explanatory words. Gainsborough, Fielding, Sheridan, Austen and Handel – even Handel’s secretary – did not apparently require footnotes, but these two not-so-eminent Victorians evidently did. When the plaque scheme was first launched in 1899, it had been agreed to include just a name, the period of residence or dates of birth and death, because ‘it was not to be presumed that the citizens and visitors would be ignorant of the life and history of the person so honoured’. Well, in this case, that was precisely what was presumed.

The plaque is dedicated to the scientific instrument-maker John Arthur Roebuck Rudge who – says the inscription – was ‘the first Englishman to produce moving pictures by means of photographs mounted on a revolving drum’, also to ‘his friend William Friese-Greene . . . the inventor of commercial kinematography being the first man to apply celluloid ribbon for this purpose’. Rudge had lived in New Bond Street Place (next door to the plaque). Friese-Greene had lived at 3 Old Bond Street in 1876 (at the age of 21) before opening his shop as ‘the Bath photographer’ at 7 The Corridor a year later and then adding another outlet at 34 Gay Street in 1881. The research partnership of these two inventors, dating from the early 1880s, the plaque concludes, meant that ‘Kinematography can thus be attributed to the labours of these two citizens of Bath where this wonderful invention received its birth’. In other words, together they overtook Thomas Edison, the Lumière brothers and others in the race to create and project motion pictures.

The plaque was sponsored by bookbinder Cedric Chivers – a committed promoter of all things Bath, elected six times as mayor between 1922 and 1928 – and it was unveiled at the beginning of December 1928 in the same decade as Friese-Greene’s death in 1921, a time when the inventor was being hastily, and it has to be said sentimentally, rehabilitated. We know it was Chivers because – most unusually – the plaque bears the name of its donor. It was as if the inscription was saying to citizens and visitors ‘this is my judgement – it may not be yours’.

Friese-Greene famously died of heart failure, in somewhat ironic circumstances, in May 1921 at the age of 65 shortly after giving an impassioned speech about the parlous state of British film culture to a gathering of senior businessfolk (mainly film-distributors) in London’s Connaught Rooms. He had only one shilling and tenpence in his pocket – the price of a cinema ticket – a pawnbroker’s chit for a pair of cufflinks and a short reel of film. In a fit of collective remorse – Friese-Greene had become an almost forgotten figure by then – the industry decided to give him a Hollywood-lavish and much-publicised send-off. The funeral at Highgate Cemetery was covered by a newsreel camera; the coffin was decorated with a floral tribute showing a camera and an end title spelled out in purple flowers. The architect Sir Edwin Lutyens (of Cenotaph fame no less) selected a suitable burial plot. An elaborate neo-Gothic memorial sponsored by subscriptions from film people and erected in 1925 marked his grave (‘The Inventor of Kinematography . . . His Genius Bestowed Upon Humanity the Boon of Commercial Kinematography’) and the industrialists headed off any adverse publicity about their neglect by asking exhibitors in cinemas across the land to honour the great man’s memory by turning their projectors off for two minutes’ silence at 3.00pm, the moment of his interment.

Meanwhile, the collector and flamboyant showman Will (Wilfred) Day was writing a series of articles in the Kinematograph and Lantern Weekly about ‘how the film was invented’, which argued increasingly forcefully that Friese-Greene had indeed created and patented a moving-picture camera before anyone else; that he had successfully projected moving images to an audience; and that he was therefore the unheralded pioneer of the movies. Friese-Greene’s name had been submerged by those of Edison and the Lumières, among others, who were much better than he was at publicity and entrepreneurship. In 1922, an exhibition of Rudge’s and Friese-Greene’s relics, which Day had lovingly assembled, opened at the Science Museum in South Kensington, which helped to promote the cause. This was the context for the unveiling of the plaque in Bath, and of its wording.

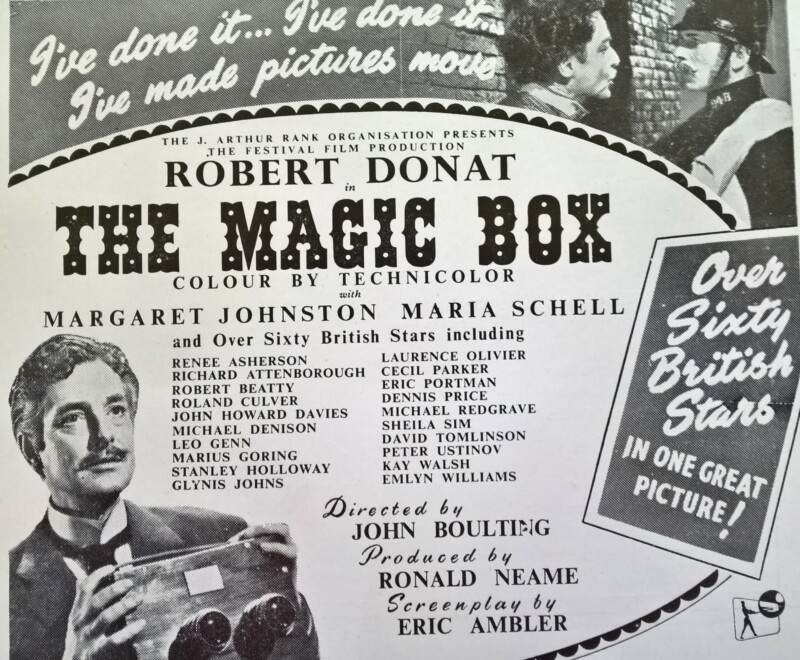

Dissolve to 1951. I first heard the name William Friese-Greene when I saw the film The Magic Box (John Boulting, 1951), the film industry’s official contribution to the Festival of Britain. I can’t recall exactly when or where I saw it, but I do remember visiting London’s South Bank at the age of five and being deeply impressed even then by the refreshingly clean and modern architecture of the Festival Hall, the 300-foot-tall Skylon, and the Dome of Discovery, and by the thrills and spills of the big dipper, the water-chute, the caterpillar and the tree-top television camera in Battersea Pleasure Gardens. When I appeared on the large TV screen situated down below in the funfair, I exclaimed to my mother, ‘This is wizard!’. I even shook hands with a cube-headed metal robot whom I was inspecting at close quarters through my round National Health spectacles. Bliss it was in that dawn . . . Of the buildings and constructions, only the Festival Hall now remains, with its restaurant called ‘The Skylon’ – the innovative Telecinema (3D! Stereophonic Sound!) soon made way for the National Film Theatre – but The Magic Box is, 70 years later, a lasting trace of those heady days when British ingenuity, and a domesticated version of Modernism, were being celebrated as a tonic to a tired nation.

So, my memory of The Magic Box, conflated with my other memories of the festival, was of a nationalistic biopic, Hollywood-style, about a great and unsung pioneer; a piece of flag-waving about how the Brits are great at getting there first but not so good at investment; a stuffy tribute presented by a cinematic poet laureate. A bit like the concluding words on that plaque in Bath. And yet, looking back, it isn’t like that at all. It is much more interesting. Yes, the film is based on a piece of hagiography called Friese-Greene: Close-up of an Inventor, first published in 1948, by a style journalist from Northern Ireland called Muriel Forth (she of Manners and Moderns) who wrote under the pseudonym of Ray Allister, an anagram of styler and stellar. But what is surprising is how careful the script by Eric Ambler is to acknowledge the controversies surrounding Friese-Greene’s contributions and to avoid making any extravagant claims on his behalf.

The film was originally to be entitled The Shining Light; then A Man Called Willie Green; and finally – after shooting had begun at Elstree on New Year’s Day 1951 – it became The Magic Box. The late change of title was certainly prudent: A Man Called Willie would have made it sound like a Donald McGill seaside postcard, a sort of precursor to the Carry On franchise. The Kine Weekly (as by then it was called) announcing the start of production, noted with evident relief that ‘The script avoids any points which might cause arguments between interests within the industry’. The opening credits are played over incised monuments to the other claimants Edison, and the Lumières, as well as (surprisingly) Marey and Le Prince, while Friese-Greene’s name has to wait until the end before it earns a place in the same pantheon as ‘a pioneer of the cinema’ – not ‘the pioneer’, note. We see The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat by the Lumières (plus the apocryphal story of the audience ducking for cover) before we experience Friese-Greene’s moment of triumph. And we learn, in a touching sequence involving the inventor’s son Graham, that his name has not been mentioned in an encyclopaedia the boy has been reading. It says instead that Edison was the pioneer. ‘You did invent the moving pictures, didn’t you father?’/ ‘Yes I think I did. I wasn’t the only one. But I think I was the first – the first patent anyway . . . in that sense, I was the first.’ Which was true: Friese-Greene did indeed patent (in collaboration with a civil engineer) a process for ‘taking photographs automatically in a rapid series with a single camera and lens’ in 1889, and then presented it to the Photographic Society in Bath the following year.

For most of the film’s running-time, Friese-Greene is presented as a gentlemanly, unworldly, idealistic man with a melodious voice (‘to capture movement – movement is part of the beauty of things’) – rather like Leslie Howard as designer R J Mitchell in The First of the Few and perfect casting for Robert Donat – who ends up a three-times bankrupt, and whose family falls apart as a result. Only in the second, delayed flashback – lit more brightly than the first by cinematographer Jack Cardiff – do we see the hero actually succeeding at something. The Magic Box – like Scott of the Antarctic and Bonnie Prince Charlie, both made at around the same time – is about an heroic failure, another great British tradition. In Hollywood, the climax would have been a public trial followed by vindication – and a triumphant montage of the hero’s legacy. The Magic Box instead ends with the penniless, exhausted Friese-Greene sitting down and dying after he has tried in vain to persuade the film industry to ‘grow up with its audience or it will die . . .’.

The film was intended to coincide with the festival – it was financed, written, filmed and distributed in double-quick time, less than a year – but only just made it: the premiere was on 18 September, just 11 days before the official end of the festival, and it wasn’t generally released until early 1952. The marketing stressed that it featured ‘over sixty British stars of stage and screen’ – many of whom, like the key technical crew, had donated their services, worked for minimum union rate or deferred their reduced salaries – and that this Festival Film was the colourful story of ‘the man who designed and operated the first practical cinema camera’. Much of the pre-publicity centred on Sir Laurence Olivier’s three-minute guest appearance as PC94B – filmed over a weekend during rehearsals for his productions of Antony and Cleopatra and Caesar and Cleopatra with Vivien Leigh – who, while patrolling the back streets of Holborn, unwittingly becomes the first person ever to view motion pictures. Friese-Greene runs into the street, hollering with joy, ushers the suspicious constable into his dingy, rented studio, then over-excitedly projects his flickering images – eight frames per second – onto a crumpled bedsheet. ‘That’s Hyde Park,’ says the by now amazed policeman. ‘Where’s it come from? And where’s it gone to? . . . You must be a very happy man, Mr Friese-Greene!’

Actually, this piece of folklore didn’t happen to Friese-Greene at all. It was originally told about the film pioneers Robert Paul and Birt Acres – in another ‘eureka’ moment – when first they managed to get their own film running in a Kinetoscope machine, at Paul’s workshop in Hatton Garden (February 1895). It seems to have been the irrepressible Will Day who transposed the story to his hero when talking to a journalist a few days after Friese-Greene’s death. There had, said the original account, been ‘such a cheering’ (from Paul and Acres) ‘that the police came in to know what was the matter’. Since then, this incident had appeared in print as a Friese-Greene story a few times, in books such as Luke Wood’s Romance of the Movies (1937), and Allister included it – briefly – in her chapter ‘I’ve got it!’. Eric Ambler added some poetic licence. The film’s pressbook rashly claimed: ‘That Friese-Greene succeeded in 1889 in showing the first results of his work to an audience of one, a bewildered City policeman, is established fact.’ It devoted a whole page to that one sequence – with stills of Donat and Olivier – under the headline ‘At last – the amazing achievement!’. As historians of film technology have noted, the wood-and-brass machine used by the inventor to project those images of cousin Alfred and his boy in Hyde Park wasn’t in fact available to him at that point in his researches – it’s a replica of his stereoscopic camera – and in any case it didn’t function like that. Oddly, the production did make a replica of the actual machine used by Friese-Greene but decided for some reason not to make use of it.

So, on the screen the magic box was the wrong box. Never mind. It made for one of the most memorable sequences in the film. Olivier had been sent the script to choose which if any cameo role attracted him – and he chose well: one theatre critic reckoned that Olivier’s performance as PC94B was ‘a vastly more reticent piece of acting’ than his pantomime villain Richard III on the stage, and all the better for it.

Also memorable was the meeting between Henry Fox Talbot (Basil Sydney) and Friese-Greene at Lacock – where ‘the man who invented photography’ (no mention of Daguerre and those squabbles over patents) gives an emotional speech about innovators and original thinkers who ‘mustn’t mind looking foolish’ to conventional society, if they are to remain true to themselves. This speech is the heart of the film, and the key to its attitude towards Friese-Greene – who replies with his vision of making ‘a camera that will photograph movement’, a piece of dialogue filmed by John Boulting through the flames of a roaring fire. In the film, it is Rudge (Cecil Trouncer) who introduces the two gentleman-inventors. In fact, Friese-Greene worked with Rudge in the early 1880s, Fox Talbot died in 1877, and there’s no evidence that the two men ever actually met. Again, never mind. It is stirring stuff. The sequence occurs during the second flashback, where it is cross-cut with a concert given by the Bath Choral Society in the Assembly Rooms: a parody of a ponderous Arthur Sullivan oratorio is being conducted by the great man himself (played – as an in-joke – by the prolific conductor of film music Muir Matheson). ‘My true love has forsaken me – where is he?’, warbles the choir with Joyce Grenfell much in evidence, as soloist Friese-Greene, who has forgotten all about the concert, continues his fateful conversation with Fox Talbot several miles away. His wife Helena is publicly humiliated by this – and they decide to leave Bath for London.

Reviewing The Magic Box, the New York Times wanted it to be more explicit about the claims it made for the hero: the main problem with the story, it said, was that the film did not have enough ‘association with historical events’, but at least it shone a spotlight on ‘an almost forgotten Englishman’. Others in the United States took a more aggressive stance. One commentator claimed that this was a blatant attempt to establish England rather than America as the homeland of cinematography, which was probably a plot by the socialist government (half the funding for the film did come from public money). The production issued a defensive press release stating that America had Edison, France had the Lumières and we had Friese-Greene and let’s leave it at that.

Whatever the reason, the film was not a success at home or abroad. It cost £220,000 and earned just £82,398 in the UK and hardly anything Stateside. The young Martin Scorsese loved it and called the scene where Friese-Greene explains the concept of ‘persistence of vision’ with the aid of a flicker-book ‘one of my primal film experiences’. But the British public preferred another biopic doing the rounds at much the same time, The Great Caruso – in which Mario Lanza sang Gounod’s ‘Ave Maria’ at a midnight Mass and declared that a crowd of American groupies singing ‘Happy Birthday to You’ was ‘the nicest thing that ever happened’ to him. Were these things actually experienced by Caruso? Swept along by the sentiment and the singing, the public didn’t seem to mind. But Friese-Greene was somehow different. Attempts to rehabilitate or reappraise his contribution had always proved controversial. He’d been neglected, then venerated. The over-the-top flag-waving of the 1920s was eventually to lead to an equal and opposite reaction, and to a strong tendency in the 1950s to diminish his contribution.

But . . . every time I walk past that plaque in New Bond Street Place, and reread the inscription, I think of The Magic Box with all its contradictions. And the look on the face of PC94B, while he struggles to maintain his dignity.

Sir Christopher Frayling was formerly Rector of the Royal College of Art, Chair of Arts Council England and a Governor of the British Film Institute. A long-term resident of Bath, he is a writer, an award-winning broadcaster on network radio and television, and a film critic.

Audio Recording

Listen to an audio recording of Christopher Frayling reading his essay at the SoundCloud link below.