On Not Watching My Own Private Idaho Niven Govinden

Share this

I’m rewatching Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho with a view to my own safety. Seeing the film on its UK release in spring 1992, a few weeks shy of my nineteenth birthday, was transformative. It followed similar cinematic experiences around the same period, watching work from queer film-makers Derek Jarman, Tom Kalin and Gregg Araki, where I saw something of myself on the screen, saw a world or a sensibility that felt like mine (or could be), but the essence of Idaho, particularly down to the intensity of River Phoenix’s and Keanu Reeve’s performances, stayed with me and would not let go. What played out that evening in a mostly empty screening room in Richmond, was a queer film that wasn’t a queer film, and a buddy road movie that went further than the template. On every level, it was a film that seemed to bend the rules in a way intended to thwart the viewer, as if to say, if you’re a queer kid, don’t watch it expecting a happy ending, and if you’re a cineaste, prepare to have your preconceptions of the mid-West milieu fucked with. I was still in my first year at Goldsmiths studying film, and my head was full of theory, but the film struck closer to home. What can never be overstated is the experience of seeing something of yourself on screen when you yourself are not the default. Idaho is hardly brimming with queers of colour yet the film felt like my life – most intently in River’s search for a place or people that were his – this search for utopia. The magic of cinema is the suspension of disbelief yet also is the amplification of belief. All that you wish to personally project coming to the fore; of seeing a dream realised. My reluctance over the years to see Idaho again was the fear that I wouldn’t have the same feelings because my yearning to escape wasn’t what it was. The film had given me plenty and that was enough – yet curiosity remained, the desire to pick a scab never fully abating, no more so than recalling the visual language. When I think about how I write books now, my preoccupation with tone and creating a sense of space partly originates from Van Sant’s grammar making such an impression on me. There are other films I can credit to that also, but when I think about the lingering shots of the barren Idaho landscape, the big skies, the tracking shots of Portland and Seattle hustlers in doorways and street corners and the vérité of their confessions, I recognise a correlation in how I write fiction – not the same results, but the same desires. The magic of watching the film in 1992 was greater than the sum of its parts, of course; the precise magic itself down to chemistry, making this an essay that’s also about love, because analysis aside, how could you be 19 and queer, and not fall in love with the vulnerability of Mike (River) and the assurance, bordering on arrogance of Scott (Keanu)? I loved them and still do; loved who they were as characters, who they were as actors, and in my mind blurring the line between both. I hadn’t realised how long I’d held onto that, until I finished writing my novel Diary of a Film and saw what was left on the page; the same sense of desire between film actors and the need to merge on-screen and off-screen life. I thought about rewatching Idaho for several months in the course of writing this essay, and while I usually dived into multiple viewings without pause, something in the film’s mythology held me back. It’s not only the legend of the film I was reluctant to unearth, but also my own. In 1992 I was learning about queer possibility in London, but in my heart I was looking across the Atlantic. NYC, the home of house music and vogue balls, was where I wanted to be; the streets walked by Act Up, Suzanne Bartsch, Marc Jacobs, Willi Ninja and RuPaul, Ciccone and Bernhard. The grime of New York was elevated several stories above the grime of New Cross, where Goldsmiths was. I pounded those South East London streets in my Junior Gaultier platform sneakers and fake fur coats, but in my mind I was walking downtown to the East Village, or maybe driving through night-time LA with Gregg Araki, and then on seeing Idaho, grungy Portland became my new epicentre of queer dreaming. I’m aware of the baggage that you as a reader bring to a book – your life experiences to date, projections and prejudices, and how that shapes what you absorb from the page. I realised then that I could never write anything definitive about a film that’s so loved in the queer pantheon – all I could offer were my thoughts on where I was leading up to the film, what changed in the screening room, and where it took me afterwards. It’s why I don’t rewatch the film now – that and the need to avoid a crushing sense of vulnerability. Instead it’s safer to study the original trailer several times, where I feel transported again without losing the core of what felt important to me. I turn to My Own Private River, James Franco’s recentish recut of the film using deleted scenes as a tribute to River. It’s like watching the original film projected through a hall of mirrors, vaguely familiar yet distorted into a new shape of its own. There’s no narcolepsy here, no explicit stating of Mike’s desire for Scott (indeed, it’s very hetero in its narrative shaping), yet once again, I’m drawn in, beguiled to a story that exists beyond the screen. The shots of Mike holding onto Scott as they bike through the city still take my breath away, ditto the swag as they stalk the streets. The lofty Henry V retelling (Scott being of differing stock, and essentially a tourist in Mike’s world) is stripped away though its essence remains. So while this is all about the film, this is about everything but the film. This is an essay about fear; more specifically a fear of nostalgia; a fear to re-evaluate the person I was, and that’s okay. I’m happy with a memory of what was, rather than what is. It’s like that sometimes.

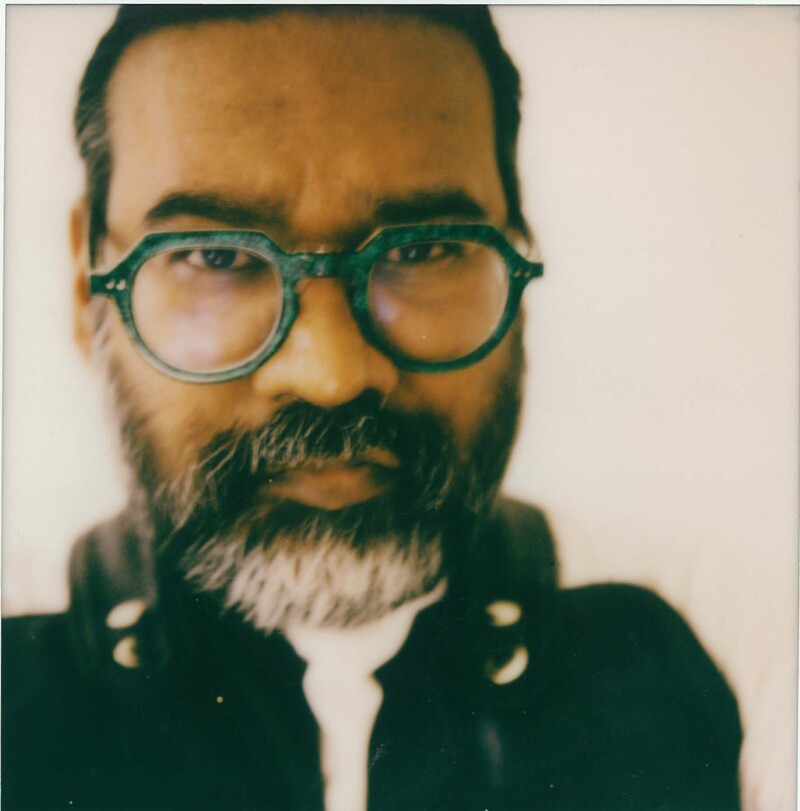

Niven Govinden is an author whose sixth novel, Diary of a Film, published in 2021, is about cinema, flaneurs, and queer love.