The Newcomers ACH Smith

Share this

Anthony – ACH – Smith writes about The Newcomers, the BBC series from 1964 in which he featured with Alison Smith.

In 1964, John Boorman was a documentary producer at BBC Bristol. For the about-to-be-launched BBC2 he wanted to make a series about the city. He asked me to script it. (I had already worked with him on studio programmes.) It is not possible to write scripts for John Boorman, as other writers have discovered since. He writes his own nowadays.

We talked a lot about formats, and were getting nowhere, when suddenly he, as it were, flipped the camera round at me and my wife Alison – she was pregnant with our twin daughters (who were published in May 1964), I with my first novel (published some months later) – and asked us to be the eyes through which he would look at Bristol.

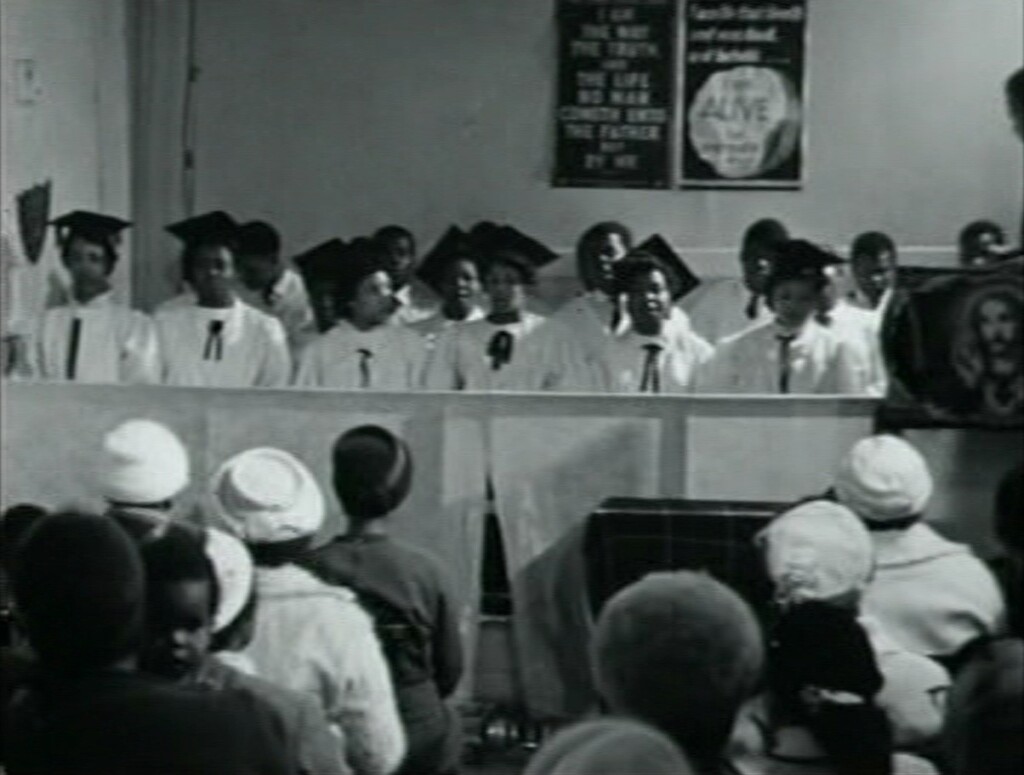

The series was called The Newcomers because we were newcomers to Bristol, and our generation represented the newly come welfare state, the new Britain invoked by Harold Wilson in the election later that year. It was Boorman who chiefly scripted it, treating it as though it were a feature film, with Alison and me, Derek Balmer and our then un-famous friend Tom Stoppard, playing the parts of ourselves.

Cinéma-vérité was in vogue. The term was lazily borrowed for a new, informal style in documentary television, made possible by the development of more flexible filming techniques. So this series was received as tele-vérité. It created interest. One reviewer wrote: ‘The future historian will be able to tell exactly what it was like to be somebody like Anthony or Alison Smith, in a city like Bristol, in 1964. Television has gained its first diary.’ For reasons I shall explain, the future historian will have no such luck. At best, he or she will be able to launch rough guesses at what it was like to be somebody filmed while undergoing a confusing experience.

Another reviewer was more disobliging. ‘These were not people who make entertainment,’ he wrote; ‘they were people for whom entertainment is made.’ Posterity took a swift sword to that reviewer: one of the people who did not make entertainment was at that time writing Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

I had some sympathy with the reviewers. They had little apparatus to help them breathe in the rare atmosphere where documentary and drama overlap. The BBC themselves were more cagey. The series was, they allowed, ‘something very artful, very created’. Huw Wheldon, then head of BBC documentaries, called it ‘television’s first novel’, which was nearer the mark than ‘first diary’.

A third reviewer said the series concerned ‘a real-life couple seen leading their own lives, or at least – as the Goons might put it – a photograph thereof’. But the Goons’ distinction is a crucial one. Anyone’s life is chiefly interior. When it surfaces, it is usually in words. Hardly ever does it express itself in the kind of neat, significant actions that a ‘television novel’ requires. And so, exactly as in a novel, actions had to be invented which would dramatise the invisible real life. We were trimmed into characters. Scenes were staged for the camera on pretexts that few people saw through. We were rehearsed in lines to speak, moves to make, expressions to register. A novelistic realism was maintained. For instance, one of the questions we ask of people we meet is, what are you doing for a living? The true answer was, we are being paid by the BBC to make these films. That, of course, would not have done, so work was invented for me to be seen doing. This was not fly-on-the-wall stuff. No flies on John Boorman.

With four of the six films in the can, Alison was told it was going to be twins – told privately by the hospital, of course, but then required to use her dramatic training to react with amazement when the scene was set up again for the camera. The series was already news. Boorman pioneered documentaries on ordinary lives, but the tabloids were having none of that – anyone appearing on television had automatically become a 15-minute celebrity. When word got out that it was going to be twins, photographers were climbing through the windows of The Paragon. Our landlady got rid of them by using her skills, too, as a former actress. She picked up her vicious little cur Jessie, unmuzzled her and threw her at the Daily Express, while shrieking, ‘Oh my god, she hasn’t got her muzzle on!’

To be trimmed to someone else’s pattern was confusing but – so what? Well, any actor in a soap can testify that people wish to tuck him or her inside the character they portray. When that character is ostensibly yourself, a powerful social force has come into play. If we tell several million viewers that we are thus, we may not find it easy to be otherwise, even on our own. Our grasp on what we believed to be our true selves was dislodged by the daily requirement that we should act out feelings that in real life are too complex, tender, and in flux to be squared off in a single sentence.

The most searching instance was the climax of the series, the birth of our daughters. Several newspapers had quoted me as saying, ‘When Alison goes into labour I shan’t know who to ring first, the maternity hospital or the BBC.’ It was a reporter’s quote, not mine, but it hit a nerve. As we held our first-born children, minutes old, in our arms, we felt called upon to perform the intensity of the moment. Neither of us did perform it, or could, even though reviewers warmed to our ‘crooning’. The point is, we felt the demand of being watched.

Why did we collude? At first it was flattering to be asked, and it would be a year’s income. When we did become uneasy it was too late. The first films in the series had been finished, and the process seemed irreversible.

My immediate reprisal was to write a cinéma-vérité profile of John Boorman. The Observer gave me a page to describe the experience of working with him, since he was the pin-up boy of documentary then. A few extracts from that follow.

*

Boorman and associate director Michael Croucher plot out the themes for each of the six programmes. We all spend days talking around the themes; each one seems intractable.

Boorman comes in one morning, after lying awake most of the night, and writes out a full shooting-script of the first film.

‘When you’re in an organisation people don’t accept it as useful activity if you just want to go into a room and think, maybe do nothing else for two or three days. So I have to do a lot of my thinking in secret, as it were. When I’m driving, or sitting at a table with a book. You have to build up defences, somehow say, “Leave me alone.” I do it all the time – flip defences, to disguise the importance to me of what I’m doing. That’s why I hate it when people come up to you after a film and say they liked it, because what they’re really saying is, “I see through you now. I see what you’re up to.” It’s a kind of indecent exposure, as though they were telling you they saw you through your bedroom window.’ He does not think dialectically. From a first idea he follows a line of others, as though testing stepping-stones until he finds a firm one, instead of building a bridge.

Directing, he doesn’t trust words at moments of tension but pushes people to where he wants them. He gives motivation, but little specific direction. ‘Accidents are important. The only limitation is time. You want to go on and on, for the chance of another accident. Often when you watch a hundred feet of film the best bit is the run-off, when the cameraman rolls the reel out and doesn’t care where the lens is pointing.’

He encourages cameramen to take a highly creative part, and is fascinated by their individual contributions. Jim Saunders, main cameraman for this series, breaks all the rules with his method of lighting. Boorman says it’s the best he’s ever known and studies it obsessively, without pinning down the logic of it.

We invented a method for recording wildtrack – voice over. Scripted, it comes out wooden; impromptu, too rambling. The best way, we found, is to script it, then throw the script away and record from memory. The pattern is still there, but the flow has to be freshly found.

For a sequence about night life we want to film in the toughest pub in the city. Another film unit took a camera in there recently, and within a minute the bar had emptied. ‘These people,’ a constable tells us, ‘they’re liquid people. Any trouble, they just melt away.’ With the publican’s consent, Boorman has a scaffolding built outside the window and covered with tarpaulins, as though restoration work was in progress. The cameraman will hide in there, unseen, and film through the window. The week before we go there, an argument in the pub leads to a killing. Boorman feels responsible for his unit, and on the evening comes into the pub and therefore, unwillingly, the film. He’s not worried that when the film goes out, and the pub’s denizens know all, they’ll remember him. ‘I have an anonymous face. I’ve interviewed people for half an hour, sat right in front of them, and a week afterwards I’ve had to be introduced again. It’s my best professional asset. No one ever recognises me.’

The first rushes begin badly. A complete reel is scratched, useless. Boorman methodically throws everything he can reach at the screen, including the telephone, which runs to the length of its cable, hits the floor, and rings. He picks up the receiver and, without waiting to hear who it is, says very quietly, ‘Go away,’ and hangs up. The rest of us feel like eavesdroppers. The scratch is identified as the fault of an assistant cameraman famous for his ill luck. Boorman: ‘It’s a kind of sin against humanity to be unlucky. It’s unforgiveable.’

‘Rushes always give the director a slight shock. Once you’ve got a shot lined up only the cameraman sees what’s actually going on the film, and it’s always slightly different from what you expect. Your own first reaction is the only one that matters, because the viewer is only going to see the stuff once.’

‘Film documentary,’ he says, ‘should be as peculiar to its maker, and as recognisable, as a novel is to its author.’ For such reasons he admires Fellini. When someone asks him what’s the best film he’s ever seen, he says, ‘I haven’t seen it yet,’ but admits that 8 1/2 came closest. He argues that Cahiers du Cinema would not have their admiration for Hollywood B-movies if the French could understand American dialogue.

He turned down two very prestigious BBC appointments. ‘I’ve got the best job in the BBC. I make the films I want to make, and I’m away from London, so there’s no one peering over my shoulder the whole time. I’ve chosen to be my own producer as well as director because it means one person fewer to argue with. Directing films is the next best thing to being God. No, it’s better than being God.’

The last of the six BBC2 films (they were later recut as three longer films for BBC1), about giving birth, presents a problem when, after two months of filming, the hospital discovers it’s going to be twins. To avoid a stagey ending, Boorman decides to announce the facts of the birth right at the start of the film. The rest will be a documentary record of what happened in Bristol during that day, 30 May 1964 – an idea that developed from the stepping-stone of someone’s remark that anyone would be interested to see the newspapers of the day of their birth.

*

After writing that profile, still the inauthenticity of our experience nagged at me. A novelist, I had allowed myself to become a character in someone else’s fiction. Anyone who knows Flann O’Brien’s comic novel At Swim-Two-Birds will recognise what happened next. My reprisal, I realised, would be a novel that fictionalised the making of the TV fiction. When that novel came out, I offered John Boorman the film rights. The perspectives go on receding forever. And when, ten years later, the BBC invited us to make a follow-up programme, directed by Colin Rose, this time I undertook to script it myself, in the third person. Alison, in the same spirit, simply invented a character for herself, and as a professional actress played it unremittingly.

But there was a reality, and it is this. Boorman’s film was not about us. The subject, as he intended, was the city of Bristol, in 1964, and the post-war generation growing up here. Even the serious newspapers didn’t really cotton on to that.

Main image: Anthony Smith, Alison Smith and Tom Stoppard look at the Clifton Suspension Bridge through the camera obscura (The Newcomers, 1964)

ACH Smith has written over 20 plays and screenplays, including Up the Feeder, Down the Mouth and Walking The Chains. He worked for 12 years for the Royal Shakespeare Company and National Theatre and toured Iran in the early 1970s with Peter Brook and Ted Hughes to write a book about their experimental play, Orghast. He has also published a dozen novels, poetry, and several non-fiction books, including a memoir, Wordsmith (Redcliffe Press, 2012). He has been Cilcennin Fellow in Drama, University of Bristol; writer-in-residence at the University of Texas; and director of the Cheltenham Festival of Literature. He has written and presented some 200 programmes for HTV and BBC.