My Work with Bristol Ideas Roger Griffith

Share this

Roger Griffith asking a question at Festival of the Future City 2015 with Clio Beeson (Bristol Ideas) (Jon Craig)

Roger Griffith MBE – writer, social activist, consultant and CEO of Creative Connex CIC – was involved with many Bristol Ideas projects. We also supported him in his writing work. Here, Griffith reflects on some of these projects and the work he did with Festival of Ideas to get into parts of Bristol which may have been missed.

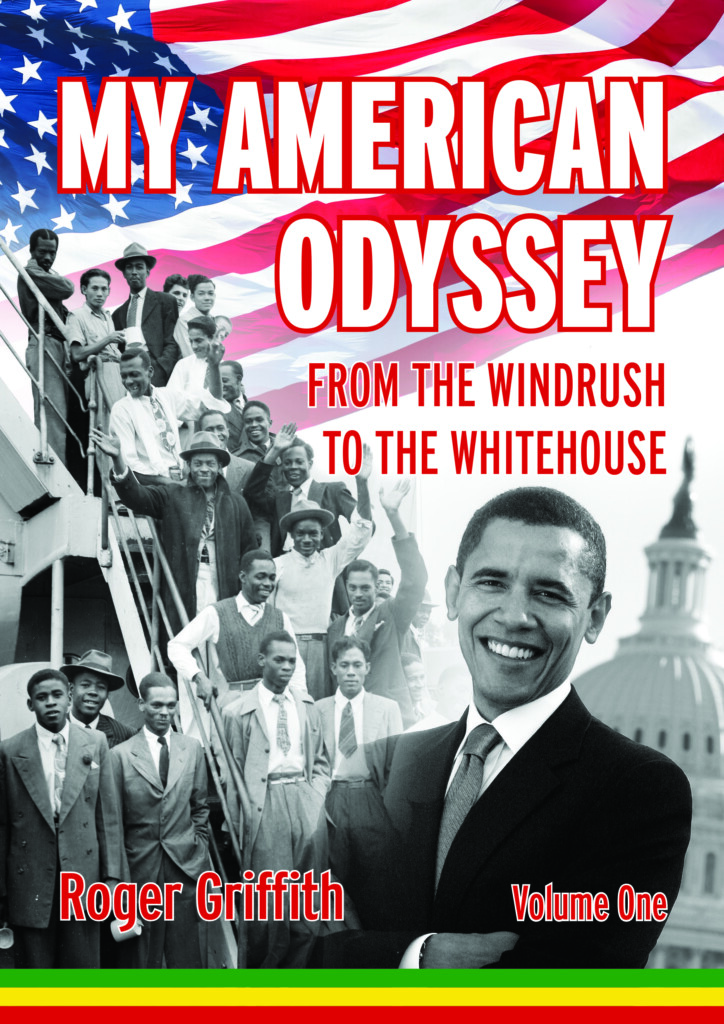

Picture the scene. A packed auditorium in one of my favourite venues, Bristol Watershed, filled with family, friends and well-wishers. Your name joins the pantheon of writers, thinkers and artists you admire, and you are introduced by a genial host. As a debut author you dream about such moments after years of honing your work in the midnight hours. Yet this dream did come true with the launch of my debut non-fiction book, My American Odyssey: From the Windrush to the White House, in 2015. Andrew Kelly interviewed me, and we presented film clips that complemented my writing about growing up Black and British and travelling through the Deep South of America. All this came after witnessing the inauguration of President Obama.

Throughout their years of giving wonderful moments to thousands, I have watched, listened to and met my heroes such as the journalist Gary Younge. His book No Place Like Home inspired my travels and writing. Meeting international artists in person, such as the writer Margo Jefferson, was also inspiring. I attended Bristol Ideas courses for working-class writers which helped my development, and the opportunity to network with new people and old friends was always a bonus.

As the former lead for Ujima Radio and member of the Come The Revolution film collective, we collaborated with Bristol Ideas on several projects to engage under-represented communities. This included giving out 1,000 free copies of The Autobiography of Malcolm X to new readers. We also partnered on a live simulcast with US politician Bernie Saunders, interviewed on stage by two Ujima Black and Green ambassadors – a programme which aimed to celebrate and promote diverse leadership and community action on environmental issues in the city. In 2023, we partnered on initiatives to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Bristol bus boycott and memorialising James Baldwin’s life and career.

Over the years, thanks to the platform I was given, my writing improved so much that parts of my 2019 Bristol Ideas essay about growing up on a Bristol council housing estate were published in The Observer. In 2021 I contributed to the Bristol Ideas book Opening Up The Magic Box celebrating 100 years of cinema about how film has contributed to my life and activism.

I will be forever grateful for the opportunities, memories and moments the fantastic Bristol Ideas team have provided and the partnerships we’ve created. You will be missed!

Roger Griffith’s essay extract which appeared in The Observer:

After her divorce, my mother chose to move to Bristol. We lived in one room in a house of multiple occupation in Easton for more than a year in 1975-6 and shared a bed that was no more than a big piece of foam on the floor.

We were offered a council flat on the top floor of a three-storey block without a lift, on a 99% white working-class housing estate on the outskirts of Bristol in Lawrence Weston. Mum didn’t drive, we were miles from friends and our Black culture. My mum – not one of life’s complainers – got a job in nearby Shirehampton and made the best of our new environment.

Aged 11, I befriended an older girl at Lawrence Weston comprehensive school who was also dating the local hard man. I was not untouchable, but I did now have someone to watch over me, as no one messed with ‘Sally’. My quick wits meant I made a range of friends from different backgrounds. You could count the number of Black families on the estate on one hand.

Due to my mother’s insistence I addressed all my friends’ parents as ‘Mr’ or ‘Mrs’. This meant I often got invited to ‘tea’, something my West Indian upbringing had no reference of, but I intrinsically knew was an important occasion. While I played with their children, these various parents would fill the gaps in the void left by the rest of my family being more than 120 miles away in London. We lived without fear of life’s everyday dangers. Soon we had a tight gang of kinship rather than terror. We fought, argued, laughed and cried together. The youth clubs, boxing gyms and a plethora of sporting clubs kept most of us away from the glue-sniffers, speed-freaks and junkies.

I miss the banter and camaraderie of life on the estate. It could be vicious, yet have the most acerbic observational humour of the finest stand-up comedians. It certainly helped to build my character, sharp tongue and canny pragmatic skills in response to an array of insults and challenges. There were no safe spaces and this sink-or-swim approach to growing up is not recommended for the faint-hearted.

As I grew older, I became more aware of the ritual racist abuse. I recall one vicious attack that took place when I was alone at a bus stop, which left me physically and mentally scarred. It was carried out by two assailants who shouted ‘nigger’ at me, individuals who hated what they didn’t understand. I was lucky, I got up: Stephen Lawrence in similar circumstances did not.

Clint Eastwood was our hero back then and I describe my time in Lawrence Weston as ‘the Good, the Bad and the Ugly’. The reality for a skinny, small Black kid on the brink of adolescence without immediate family or friends meant life was tough, but it was also the making of this man.

Roger Griffith is a writer, social entrepreneur, lecturer and activist. At UWE Bristol he has been central to work to decolonise the curriculum. He is the author of My American Odyssey: From The Windrush to the White House.

This essay is taken from Our Project Was the City: Bristol Ideas 1992-2024, published May 2024.