Future Cities and Intergenerational Solidarity

Share this

I have worked with and alongside younger and older people, including having taught in secondary schools and higher education institutions and run research and co-design projects with and alongside older adults in care homes and urban settings. Both groups experience ageism and are often excluded from city decision making and future visioning.

However, when ageism is considered in cities, generations are usually discussed separately. For instance, policy makers and commentators have turned to thinking about ‘age friendliness’ as vital to the future of our cities as our urban populations are not only growing but also getting older. At the same time there are worries about the voices of children and young people in designing and occupying our city spaces and calls for the need for ‘child friendly’ cities.

It has been argued that in our current cities we often live, learn, work and play in age-segregated spaces such as schools with increasingly high fences, hospitals tailor-made for children or older adults, playgrounds just for children and gated care home facilities. However, there is nothing inevitable about a future of older adults shut away in care homes and children garrisoned in schools.

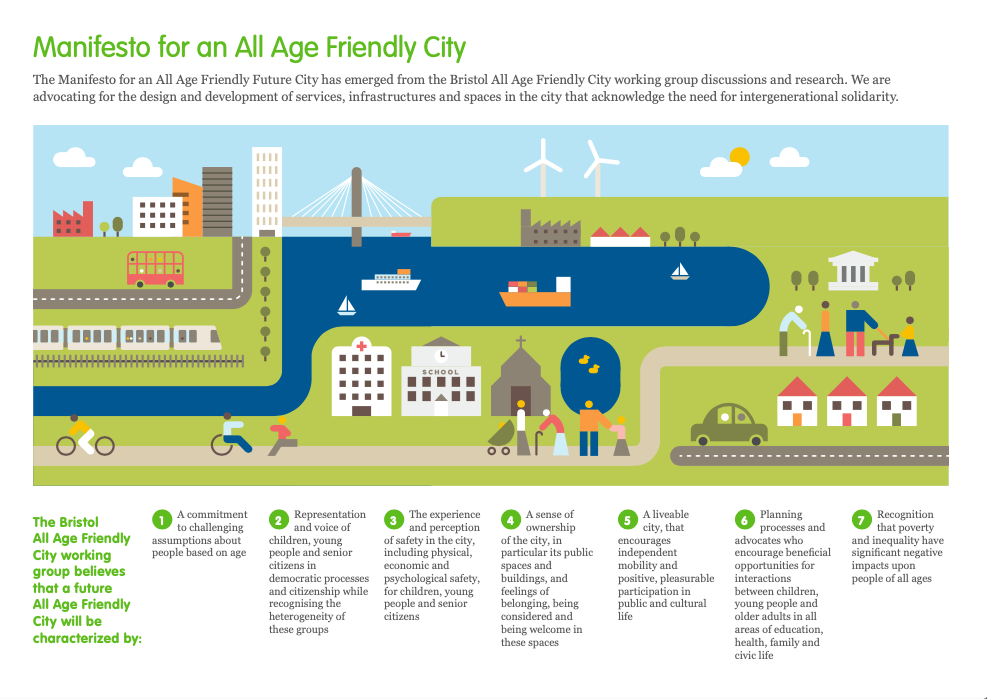

Back in 2014, I worked with colleagues to co-produce a manifesto for an ‘all-age friendly’ city. We wanted to question the idea that the intergenerational contract is broken and argue that all age groups should live alongside each other, occupy the same public spaces and have interests and needs in common.

Others have argued that we have seen an increase in intergenerational tension in our cities. This is fanned by organisations who point out the need to redress issues around the ‘fairness between generations’. They argue that while increasing longevity is welcome, government policy must be fair to all generations – old, young or those to come. Often there is a sense here that older people are doing better than younger generations who will have fewer opportunities to buy their own home, fewer retirement rights, be unable to walk into jobs for life, and who will bear the brunt of the climate crisis, a crisis made by older, richer generations in the Global North. And added to this mix are the growing and ongoing systemic inequalities experienced across our city populations, including those related to race and migration, gender, sexualities and disability.

The future is a building site

It seems we are up against it in building fair and sustainable intergenerational future cities. However, although powerful actors might want us to believe futures are already set, they are not. Futures have always been debated, planned and materialised. ‘Anticipation studies’ is a relatively new field in academia, at the centre of which is the idea of an active and reflective relationship with futures that are unknowable. ‘The future’ is seen as a building site that might involve design or political and social struggle. Futures are also understood as unpredictable, opening up possibilities for unforeseen change and disruption, for alternative futures.

Where, then, might we find the resources for our imagination in building fair and sustainable intergenerational city futures? We could look to the Seventh Generation Principle, common across many North American indigenous peoples, that any time someone makes a decision they should think mindfully and with care and responsibility about its impact on people and the planet seven generations into the future. In Wales, they have created a Future Generations Commissioner, whose job it is to be a guardian for future generations and to encourage policy makers to consider the long-term impact of their decisions. The current commissioner discusses the role of artificial intelligence and technologies in society and what it might mean across generations as well as how to live healthy active lives for longer. The United Nations International Youth Day theme for 2022 was a call to action towards Intergenerational Solidarity: Creating a World for All Ages. In Ghana, older and younger people came together to discuss and challenge ageism, for instance, enabling the learning of traditional knowledges from older adults and the sharing of experiences of ageism. These initiatives might help us all to think across all generations, including those yet to come, in building intergenerational future cities with everyone in mind.

Co-designing intergenerational cities

One of the problems we face is pluralising ideas of the future when dominant voices (government departments and international conglomerates, for instance) have taken over spaces of city futures thinking. It is not easy to think about futures right now in our complex and uncertain world, and I’d argue that there is a need to democratise our opportunities, capacities and capabilities for re-imagining futures.

In building intergenerational city futures it is essential not to be driven by expert forecasts alone, but also to co-design with diverse, cross-generational groups with different lived experiences of the city, now and through history. We need to bring these groups into co-design spaces alongside researchers, policy makers, community sector leaders, designers/artists and developers. We need to make problems and concerns visible, tangible and imaginable in a time where there are high levels of uncertainty and complexity. We must engage in mutual and collective learning and question assumptions in order to work towards desired and preferable futures. Through this process we might surface and ask questions such as: how do different generations and groups understand futures? Who owns the future? How can we live alongside other generations, including those yet to come, who understand and practise things differently? Who else needs to be involved in our design conversations? How might we act locally whilst not forgetting our global ties, histories and connections? This is difficult, emotional and maybe slow work that must involve care, trust building and long-term commitments.

I hope that the all-age friendly manifesto we created back in 2014 might be a useful resource in encouraging this intergenerational future city making work to spring up. We co-created seven manifesto principles:

- A commitment to challenging assumptions about people based on age.

- Representation and voice of children, young people and senior citizens in democratic processes and citizenship while recognising the diversity of these groups.

- The experience and perception of safety in the city, including physical, economic and psychological safety, for children, young people and senior citizens.

- A sense of ownership of the city, in particular its public spaces and buildings, and feelings of belonging, being considered and being welcome in these spaces.

- A liveable city that encourages independent mobility and positive, pleasurable participation in public and cultural life.

- Planning processes and advocates who encourage beneficial opportunities for interactions between children, young people and older adults in all areas of education, health, family and civic life.

- Recognition that poverty and inequality have significant negative impacts upon people of all ages.

These principles are only a starting point for conversations and actions. We must recognise the ambivalences around intergenerational connection in the present. We need to engage with and understand material differences in older and younger people’s being in the world in the present that are informed by experiences of the past and of futures. And we have to consider how generational experiences intersect with other social differences including class, race, ethnicity, gender, disabilities and sexualities. We might start with the cities in which we live but we also need to consider questions of transnational intergenerational solidarity and justice. I hope you are up to the challenge.

Helen Manchester is Professor of Participatory Sociodigital Futures at the University of Bristol. She is interested in participatory futures, ageing and intergenerational practice, co-design, social connectivity, culture and the arts. She develops methodologically innovative approaches to research in collaboration with artists, technologists, civil society organisations and policy-makers.