Friese-Greene: Protofeminist? (Part 1) Peter Domankiewicz

Share this

William Friese-Greene did something rather peculiar and entirely unexpected on the 25th of February 1890.

He was visiting the Bath Photographic Society, which he had helped to found and to which he made it his custom to present his latest discoveries. Today’s was a bit of a stunner. It was well-known that he had been working on a moving picture camera with the help of Mortimer Evans, but this was the first time he had ever shown it in public and it would get heavily reported. Fittingly, the title of his talk was ‘Photography in an Age of Movement’.

It started as one might expect, with some broad statements about photographic progress, the possibilities of what such a camera could accomplish – ‘It will be able to investigate all the movements of the spider making its web, or a cloud as it forms, and thousands of other things too numerous to mention’ – and his unbridled excitement when he first saw the camera working. But he really hadn’t said that much at all about his marvellous new achievement before he veered dramatically off-piste, declaring, ‘Now the next subject I shall connect with this paper, or at least the movement or movements of photography, is the ladies. . .’. It turned out that this was the ‘Age of Movement’ he most wanted to address.

Debate had recently been raging in the photographic press about whether women should be allowed into photographic societies. In general, they weren’t. Arguments included pointing out the perils of women ascending badly-lit staircases to darkrooms, handling dangerous chemicals and occupying the same spaces as men with their cigars and ribald stories, all of which would clearly be harmful to their delicate sensibilities, not to mention that it would be improper for married men to be exposed to such temptation. But beneath the excuses was a mindset which Friese-Greene openly mocked:

‘The ordinary view held by the majority of people as to the intellectual power of women as compared with men is not very encouraging to the fair sex, whose smaller brain is held to be positive evidence of smaller mind, or of no mind at all. This idea is still cherished by some, though in the face of everything tending to show the opposite it has taken a long time to convince others that women are truly capable of rising to any position above that of slavery, socially and physically. In my opinion it will not be long before we shall be convinced of the fact that women, when given the same intellectual advantages and education as men, will prove intellectually equal. I know it is difficult to realise in the increasing battle for existence that men can be confronted by rivals. An argument may be brought forward that these smaller, delicate beings, with whiter hands and long hair, are physically and therefore mentally incapable of taking an equal place with men in the intellectual world. Well, what they may be I do not know, but I do know this, as regards their intellect in connection with the fascinating art of photography, we shall find a hot competition, and one in which, if we do not help them to win a place, they will win a place for themselves.’

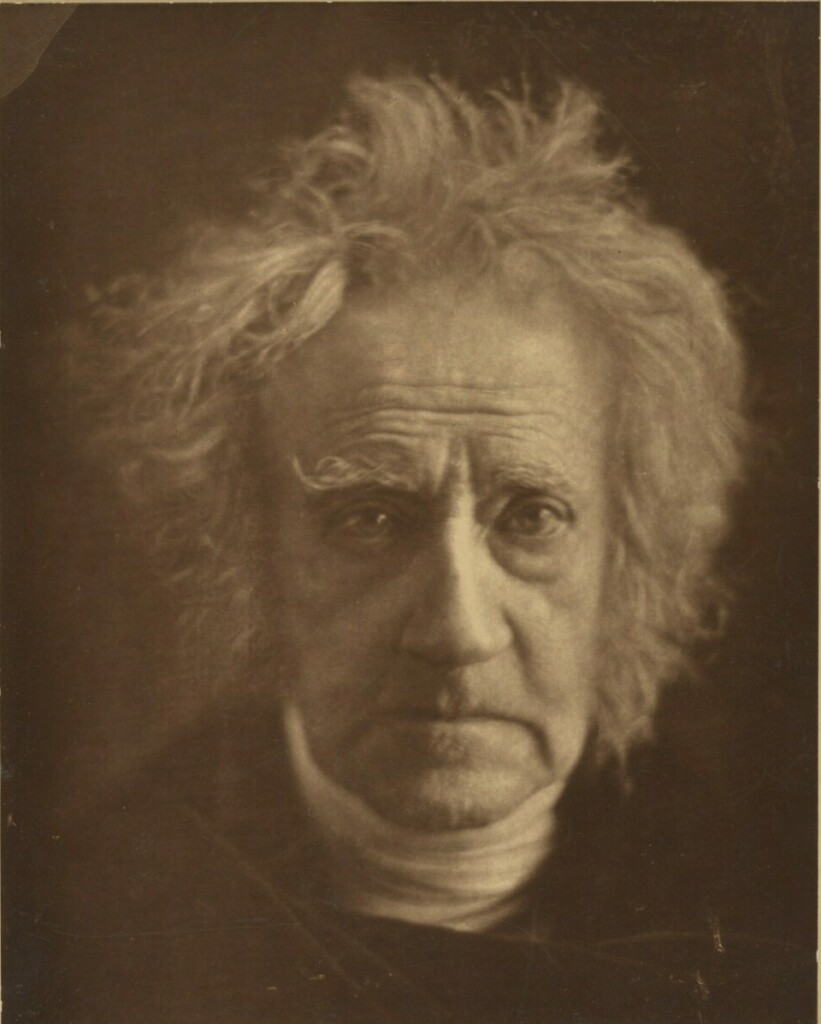

He then proceeded to offer a paean to Julia Margaret Cameron, perhaps the first British woman photographer to achieve fame, whose work was roundly criticised by male contemporaries for what they perceived as ‘defects’ of focus and processing. The enduring appeal of her work during the 1860s and 1870s to the present day has decisively proved them wrong. Nonetheless, all these years later, when Friese-Greene was speaking, it was still the case that women only participated in photographic competitions in their own category, not in competition with men.

Friese-Greene concluded by urging the society to encourage women members, just as he had done at its inaugural meeting, 18 months earlier, after which it was reported, ‘We note there is no exclusion; the society is open for ladies and gentlemen, whether amateur or professional.’ Records of the society’s meetings confirm that women did, indeed, participate.

Friese-Greene’s words echoed across the Atlantic, reaching the highly receptive ears of Catharine Weed Barnes, the most prominent female figure in American photography at that moment. Like Cameron, Weed Barnes had come from a wealthy family and had only taken up photography four years earlier, yet had quickly made a massive impact. In the December of 1888 she became the first person to ever deliver a paper before a photographic organisation in the United States, addressing the New York Society of Amateur Photographers on ‘Photography From a Woman’s Standpoint’. She then became their first female member.

Enraged by the very same comments in the photographic press that Friese-Greene was taking aim at, a year later she had had a lengthy letter published in the American Amateur Photographer, entitled ‘Why Ladies Should be Admitted to Membership in Photographic Societies’. Before long, she would become one of the magazine’s editors. In her advocacy of women in photography, she was dead set against the idea of women establishing their own photographic societies, writing ‘let us win our spurs side by side with our brothers, and the result thus gained will be worth all the trouble required. The day is coming, and will soon be here, when only one question will be asked as to any photographic work – “Is it well done?”’. A sentiment echoed by Friese-Greene’s words.

Reflecting on these debates a year or so later, when writing for the popular magazine Outing, Weed Barnes referenced Friese-Greene’s remarks as evidence of progress in thinking in Britain, albeit with a long way to go. Little did she know then that she would soon end up settling in Britain, editing photographic publications here, and bringing her uncompromising ideas to a new audience.

But Friese-Greene’s thoughts, shared that evening in Bath, did not come out of thin air: they were part of a pattern that was already emerging in his life. We’ll take a closer look at this in Part Two.

Peter Domankiewicz is a film director, screenwriter and journalist with an abiding interest in the beginnings of moving pictures.