Peter Domankiewicz Still Crazy After All These Years Reflections on Film2021 and Friese-Greene

Share this

From a Bristol backstreet to a monument in Highgate: that’s quite a journey. From controversy on the centenary of his birth to controversy at the centenary of his death, William Friese-Greene never seems to rest in peace.

It was the best part of thirty years ago, God help me, that I first met Andrew Kelly to talk about the possibility of doing something about the Bristolian moving picture pioneer William Friese-Greene, to tie in with the upcoming Centenary of Cinema in 1996. He had recently been appointed to lead an organisation called Bristol Cultural Development Partnership and knew a lot about cinema, I had been told. Back then, my research was only just beginning, little more than idle curiosity. At that time, those best-laid plans came to nothing.

Now Andrew is stepping back from his management role, in what is now called Bristol Ideas, after a colossal number of successful cultural projects, and I have taken a step sideways from a filmmaking career into a PhD about none other than William Friese-Greene. Happily, in the meantime that faraway conversation has borne fruit.

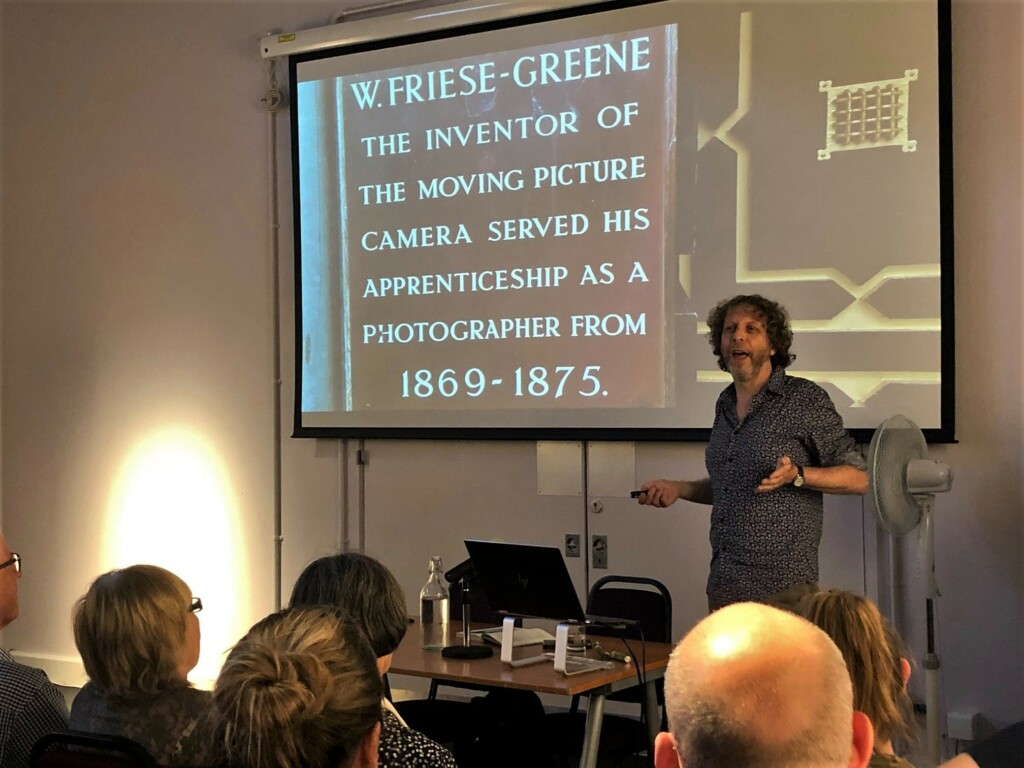

When I was invited to talk about William Friese-Greene at Cinema Rediscovered in 2019, I raised the thought that since 5 May 2021 would be the centenary of his death, we might organise some kind of events to commemorate it and have a reassessment of his achievements. Bristol Ideas took that ball and ran with it, bringing in many partners in this UNESCO City of Film and raising funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and the British Film Institute, for a year-long celebration and investigation of Bristol’s history of filmmaking and film-going.

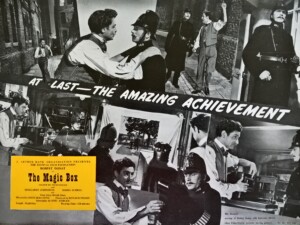

It’s been a surprising year, full of unexpected twists. First of all, Covid could have put the kibosh on the lot. Instead, it merely delayed things a bit and also meant that some in-person events went online, but that was no bad thing as it opened them up to a wider audience. At Cinema Rediscovered this included a discussion with Bryony Dixon of the BFI and Christopher Frayling, who was able to share his memories of the 1951 Festival of Britain, when the biopic The Magic Box was released, and how different the film looks now compared to how many interpreted it at the time.

The controversy around Friese-Greene can be traced back to his monument in Highgate Cemetery, on which one reads, carved in stone, ‘His genius bestowed upon humanity the boon of Commercial Kinematography of which he was the first inventor and patentee’, followed by an incorrect patent number. Given that William Friese-Greene was certainly one of the first to design a motion picture camera, but sold that early patent to people who did not commercialise it, there’s reason to question such claims. Just so, on the centenary of his birth, in 1955, the Kodak Museum told everyone who cared to listen that Friese-Greene was a liar, a failure and contributed nothing to the creation of moving pictures.

And there things have rested: a binary ping-ponging between hero status and total dismissal. I proposed something I considered not very radical at all: to take a calmer, cooler and more nuanced look at his various inventions and achievements. It turned out that this caused almost as much trouble as before. The Observer published a lovely piece about the centenary, with the journalist respecting my request to avoid implying that anyone – including Friese-Greene – was the sole originator of cinema, then a sub-editor wrote a headline claiming I was trying to have Friese-Greene declared ‘the true Father of Cinema’. The BBC put a piece online about the Friese-Greene events at Cinema Rediscovered that was frankly bizarre, written as if they were channelling a century-old tabloid journalist, making absurd claims. I formally complained about its wild, unsourced inaccuracies and they corrected it somewhat.

In the absence of alternative views, film historians have clung very firmly to the ‘Friese-Greene was a nobody’ line for over 60 years, with mine being the first fresh research in that time. But old habits die hard, and I often sense a grinding resistance whenever I propose that there may be another way of looking at him. Most recently a lengthy series of writings has re-iterated what was said in 1955, using an identical approach: selectively drawing together whatever makes Friese-Greene look bad, or spinning the facts to appear so, whilst systematically excluding all the information that might lead to other conclusions.

Many people have declared the death of nuance in relation to modern debates, especially on social media, but I refuse to give in. I find these obsessions with either making Friese-Greene into the sole originator of cinema or damning him to hell, unenlightening and unimaginative, so it has been refreshing to be able to write more broadly about the man in a series of pieces for Bristol Ideas which show him in his very human complexity. This has ranged from discussing whether he could be considered a proto-feminist, to assessing his questionable abilities as a poet and lyricist.

Ian Christie, a figure with many connections to Bristol, Cinema Rediscovered and early film, recently highlighted in a talk that ‘film history is local history’. I have seen that to be true in various ways this year. Firstly, in uncovering a network of West Country connections in Friese-Greene’s life, even when he had long since settled in London, then Dovercourt, then Brighton: personal connections from Bristol, Bath and Weston-Super-Mare who figured in various stages of his career. I would also like to highlight the work of Mark Fuller in uncovering the story of how moving pictures came to Bristol, as it is the detail of local experience that casts new light on the national picture.

My original interest in Friese-Greene developed in parallel with my growth as a filmmaker, from early experimental work and corporate videos to filmed drama, television and cinema. I always believed very much in Bristol as a great creative base for filmmakers and worked with the film and video workshop Picture This to encourage them. That said, in the 1990s it was very tough going and London looked a long way down its nose at ‘the provinces’. So, it was gratifying to take part in the Festival of the Future City to reflect on what had changed over the decades and forward to what is now possible. William Friese-Greene certainly did not allow issues of his humble origins to constrain him and was always excited by the possibilities of new technology.

I was particularly pleased to be asked to contribute to a book, edited by Melanie Kelly and published by Bristol Ideas, Opening Up the Magic Box: Friese-Greene and Reflections on Film. It brought together the story of a film inventor – in fact and on screen – with filmmakers, film critics and that most vital element: the film audience. All of these are inextricably interconnected into a form of art, entertainment and communication that is so deeply embedded into our world, that it would never occur to us to imagine its non-existence. But in the late 1880s it was just a wild dream in the minds of a handful of people, one of them a working-class lad from Bristol who had turned himself into a well-known name in photography.

What powers the dreamers, those behind the screen and those sitting in front of it, is a matter of wonder, and more than just cause for a year of celebration.

This essay has been commissioned as part of our Film2021 project. Visit the project page to find out more.

The Film2021 project is funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The author of the essay retains copyright and text cannot be used by others without his prior permission.