English City A Vision of Bristol in 1945

Share this

One of our favourite old books about Bristol is English City, which was published by J S Fry & Sons Ltd in 1945 in the closing months of the Second World War.

The book was aimed at a young readership and was distributed free of charge. Its subtitle on the cover is The Story of Bristol, but on the title page it is The Growth and Future of Bristol. This was as much about thinking about how the city would be rebuilt after the war as it was about looking back.

From the foreword:

‘As a Firm which has been engaged in manufacturing in Bristol for over 200 years, we felt that we should like to make some contribution towards the re-birth of our city. A vivid, yet simple account of the main features of the story of Bristol – particularly at this time when we have lost so many records of the past – seemed appropriate […] Without blinding ourselves to the faults and failures of the past – and there have been many – we hope the brief story which follows will show that Bristol has hitherto played a worthy part in the history of our island. We now find ourselves faced with new and difficult problems. If we are of the stuff of which are forefathers were made, we shall face them fearlessly, and our solutions will be, once more “Ship-shape and Bristol Fashion”.’

(the phrase ‘Ship-shape and Bristol Fashion’ refers to ‘Bristol shipwrights of bygone days [who] built so well that their skill became a byword’).

A committee was formed by the Bristol Education Department to oversee the project and assistance given by the City Archivist (Elizabeth Ralph, who carried out the research), City Engineer, City Architect and Town Planning Officer. The author was Harold G Brown with visuals by Paul Redmayne. The book was published by University of London Press Ltd.

The story begins in the reign of Ethelred Unrede (978-1016) with coins minted at Bricgstowe (the Place of the Bridge) and continues through to the ‘blight of war’ and the Bristol Blitz.

‘[…] as the debris was removed, one redeeming feature became clear. The problem of replanning the centre of the old city was enormously simplified. Enemy bombs had cleared the site for us, and a unique opportunity offered to rectify the mistakes of the past. As an antidote to the destruction surrounding them, men and women began to make plans for reconstruction.

Themes addressed in the section headed ‘When Bristol Rebuilds’ include neighbourhoods, homes and schools, the air we breathe, the factories we work in and what was to be done with the city centre.

The image below is of the proposed post-war development of Southmead by J D M Harvey. At the time English City was written, it was hoped that this would be one of many such compact, self-contained districts across the city (neighbourhood units), each with its own amenities.

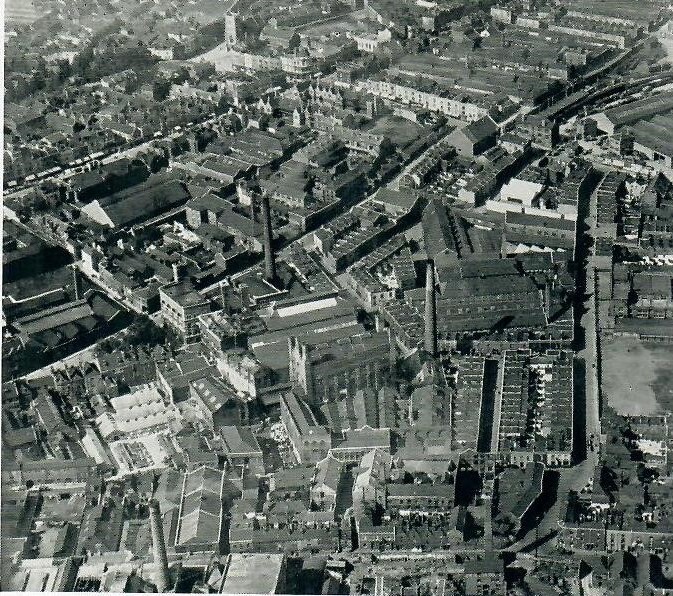

Looking back to the period just before the war, the author writes of how some people ‘were condemned to live in houses crowded between the factories, with their outlook bounded by brick walls and smoking chimneys. Such dwellings could have little in the way of gardens – a backyard was the best that most of them had room for.’ While a fortunate few could afford to live free from the city smoke in residential Clifton, many were moved away from the slums into municipal estates that had been carefully planned and provided gardens for all. The photos below contrast the clutter of Broad Plain in the city centre with an aerial view of Hillfields. The planned estate was also seen as being better than ribbon developments in which the ‘town invades the country’, following the course of major roads.

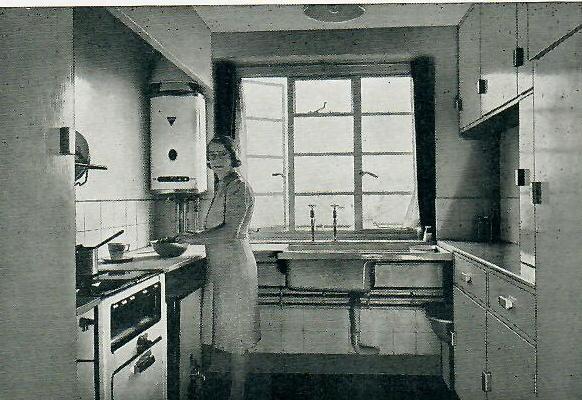

A double-page spread looks in detail at what it was like to live in a property located at Barton Hill – one of the city’s older districts. Most of the ground floor is used to accommodate a corner shop. There is only a tiny backyard; the kitchen is cramped; living rooms open directly on to the pavement; there is no inside sanitation or baths; the surrounding streets are described as ‘monotonous’; and there is nowhere for children to play away from the street.

This is then contrasted with life on the Sea Mills Municipal Estate before the war. Every house has a garden, bathroom, hot water and indoor sanitation. Kitchens are better and brighter. Children are close to fields and parks in which they can play. The downside of living here is that there are few shops and the half-hour journey to the city centre for work costs 4d.

Looking ahead to the home of the future the author writes: ‘Modern architecture in other cities has proved that houses can be both beautiful and practical’. Having said how much better the kitchens of the municipal estates were in comparison to the older homes (below left), he says ‘even greater improvements are planned for those in our post-war homes’. Below right is a photograph of one of two experimental kitchens which had been built on a Bristol estate with fitted cooker, sink and cupboards. Other ideas that ‘should do much to lighten the work of the housewife’ include smokeless grates, sink disposal units, more spacious rooms, more easily available electricity and gas.

In the conclusion to English City the author writes:

‘We have tried to show how the government of the city has gradually become more and more complex, yet, at the same time, how the responsibility of local government has been extended to an ever-increasing number of its citizens. The success of democratic government depends upon the degree to which the citizen is prepared to carry out his duties. It is significant that in many local elections before the war only one out of three electors used his vote. A new chapter is opening in the city’s history. The standard set in the past has often been a high one, but that of the future must be higher still. The attainment of this will depend on the interest the citizens of Bristol show in the moulding of the future of the city.’