Don’t Give Up the Day Job, Mr Friese-Greene Peter Domankiewicz

Share this

This essay has been commissioned as part of our Film2021 project. Visit the project page to find out more.

WHO IS THE BELLE OF CLIFTON?

Is she dark, or is she fair;

Auburn locks or golden hair;

Hazel eyes or sweetest blue;

Laughing eyes or grave and true?

If you would see her beauty rare,

To Queen’s Road Institute repair;

For there her photo may be seen,

Charmingly taken by Mr. FRIESE GREENE.

It was hardly the most conventional way of promoting one’s business, but it got attention.

In 1880 Willie Green of backstreet Bristol had successfully transformed into William Friese-Greene of booming Bath and had plans for expansion, with the name he had established as the cornerstone. First would come a studio in Plymouth, where one of his brothers had settled, then the chic environs of Clifton, then a second Bath studio, custom-made in Gay Street, with its own gallery. It was around this point that he had a stroke of marketing genius: advertising his businesses with poems.

(Peter Domankiewicz’s Collection)

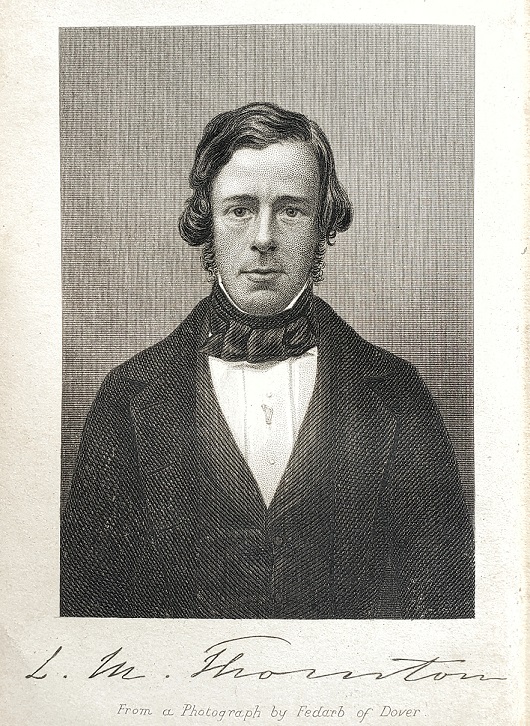

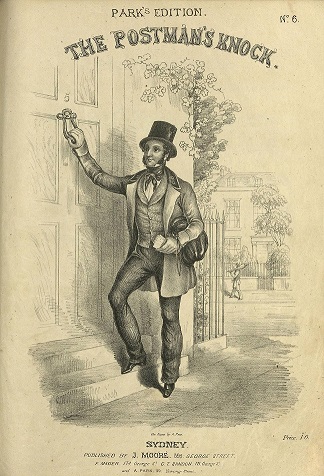

This inspiration came from a rather unlikely source: the somewhat forgotten wandering versifier Lewis Mansel Thornton. Never knowing his father, Thornton grew up in Derby, where he published his first book of poetry at 19 years of age, which had enough subscribers to run to a second edition. But his name was made in 1856 when he penned a paean to the thrill that had now come within reach of ordinary folk, thanks to the Penny Post: receiving a letter. Set to music by W T Wrighton, ‘The Postman’s Knock’ became an international hit and a music hall favourite, especially when performed by a singer in uniform with a real door to rat-tat at the appropriate moment of the catchy chorus. It even spawned a London show.

Such was Thornton’s success as a lyricist that an edition of Diprose’s National Song Book from that time has no less than 48 entries penned by him. But the truth was that lyric-writing often only attracted a one-off payment: composers, performers and publishers all earned more from the songs. Having married Margaret Barr in Leeds, they began a peripatetic life, their son born in Cheltenham. Thornton was selling lyrics for a guinea where he could, or perhaps a volume of verse, and in 1860 he was already asking for charitable assistance. Come 1871 he could be found living with a different woman, Mary, in Bedminster (distinct from Bristol then), with whom he had moved to Bath by 1880.

Whether it was in Bristol or Bath that William Friese-Greene first encountered Lewis Thornton is unknown, but that encounter made an impression on the younger man. It seems that, initially at least, Thornton wrote some of the advertising verses for payment, but Friese-Greene decided to also try taking up the pen, and stated, ‘it was by the help of his encouragement and advice that I got over many a harsh criticism.’ As to that criticism, well, one of his own stories sums it up, combining the cheeky confidence of the ads themselves with a sense of humour about their lyrical limitations:

‘One morning the respected editor of the Bath Chronicle (with whom I was acquainted) met me and said “Well Greene! How’s business?” I replied “Brisk and flourishing,” whereupon he told me that some one had said to him referring to my advertisements “How is it such a good paper as yours inserts such trash?” He replied “Do you read it?” The answer was “Yes!” “Well” said the editor “that’s all Mr. Greene wants.” The Critic was silenced.’

There’s no such thing as bad publicity, as they say.

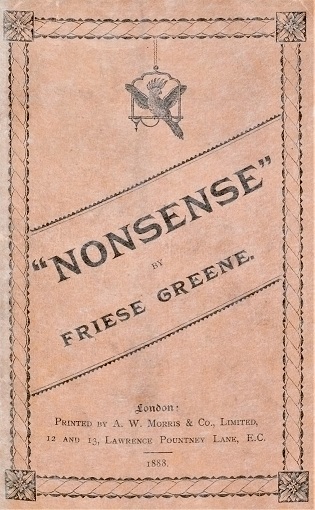

The ads covered a few years around 1880 but although Friese-Greene mainly wrote verses whose themes and stories led inexorably to one of his studios, he did also privately pen some on other subjects – principally photography and love. Now in London and doing well, he published a collected volume of promotional and personal verse at the start of 1888, self-critically entitled Nonsense. Alongside some 200 of his own short pieces, Friese-Greene included half a dozen by Thornton, whose encouragement he acknowledged. Thornton, by then relying on the Bath workhouse for survival, would die a few months later, so this was the last time his work ever appeared in print.

(Photo taken by Peter Domankiewicz)

Superficial though these poems mainly seem, within them there may lie clues about Friese-Greene’s views on life. In ‘We’re Living in a Very Funny Planet’ he observes:

A bright idea at once a head shall enter,

Which worked out, will a fortune realize;

Another shall toil hard from spring to winter

And fail to win the deeply yearned for prize.

Certainly, his failure to see ideas through to commercial success would make financial survival a repetitious theme in his life:

I yearn not to be singled out

While mingling in the throng;

But this I need, beyond a doubt,

Enough to move along.

Although Friese-Greene did not take himself seriously as a poet, and with reason, his verses flow distinctly better than his mentor’s. When news of Thornton’s pauper’s passing reached the world, the acerbic tone that was so popular with writers (and readers) of the day was not put aside. In Britain one commented, ‘The death of Mr L M Thornton (in Bath workhouse) is scarcely an event that calls for an expression of national mourning, albeit the author of The Postman’s Knock did by means of that very silly production achieve something like lyrical fame.’ Whilst in Australia, where it had been a hit too, an obituary bluntly concluded, ‘We must not allow our regret at poor Thornton’s end to blind us to the fact that he was in no sense a poet… There is a poetic fitness in a Burns or Chatterton dying poor. But the muses had no laurels for Thornton.’ To which one feels inclined to respond, ‘No please, don’t hold back, tell us what you really think. . . .’

Further inspired by Thornton’s example, Friese-Greene likewise ventured into lyric-writing and, in doing so, opened himself up to just such criticism. It started well enough, with The Graphic’s music reviewer concluding in 1886 that ‘The Soldier Who Bled For His Queen’ was ‘a very good specimen of its type.’ The next year was Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee which brought forth an avalanche of musical tributes to her fifty-year rein, including Friese-Greene’s and Florence Gibbs’ ‘Light of our Nation’ in which he borrowed from Wordsworth to declare her ‘a perfect Queen, nobly planned’. One reviewer considered, ‘The words are good and the air (written in A) appropriate, with a nicely arranged accompaniment’, another that it was ‘more remarkable for loyalty of sentiment than for uniqueness’ and The Graphic that it had ‘nothing to distinguish it from a host of other well-meaning but commonplace songs.’ Nonetheless, newspaper reports reveal it was sung at some public events.

William’s daughter Ethel had some talent for music and was to be found singing and playing the piano at various events. In London she was even taught at the Royal Academy of Music: until, that is, her father went bankrupt, and the classes abruptly ended. Now, as a parent, it is easy to stray into being too proud of our darling’s achievements and this is perhaps what led to her being encouraged to publish one of her own compositions at the end of 1890, a few months before that disaster struck.

The Daily News didn’t hold back, ‘Juvenile prodigies are as a rule bores, and Miss Ethel Adelaide Friese Greene, aged 13, is no exception to the rule,’ whilst one can almost hear The Graphic’s critic rubbing their hands together before firing off, ‘It is well that the youth of Ethel Adelaide Friese Greene, aged 13, should be announced on the frontispiece of “A Sigh,” written and composed by this precocious young lady, otherwise this crude composition, with its feeble and halting verses, would have been passed over in silence. It is devoutly to be hoped that a limited number of copies for admiring relatives and friends will be published in future, when juvenile composers who have scarcely left the nursery are bold enough to challenge public criticism.’

Neither William nor Ethel would ever attempt to place one of their compositions in the public domain again.

But before that, William had one final poem to put out into the world, which was published on both sides of the Atlantic. 1889 was the 50th anniversary of William Fox Talbot’s announcement of his photographic process and Friese-Greene had been chosen to deliver the keynote address at the London Photographic Convention on the early experiments of the man who was his idol. He ended his speech with these considered lines, which perhaps prefigure the motion picture camera that even then was being constructed for him:

Photography is like magician’s charm–

We nurse the absent, in affection warm;

Present the distant, and retain the dead–

Shadows remaining, but the substance fled;

For faces vanish like the dreams of night,

But live in portraits drawn by beams of light.

Exquisite nature caught in changing dress;

Motion in photography appears at rest.

The Film2021 project is funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The author of the essay retains copyright and text cannot be used by others without his prior permission.