Council Estate Memories: Woolwich John Savage

Share this

The death of my father soon after the end of the Second World War – a drawn-out process from the outcome of his Royal Navy service – pushed my mother and her two children into a return to her own parents’ home in the bomb-damaged slums of Woolwich, South London. My brother was eight and I was young enough to have retained no recollection of my dad at all.

The house was a private rental in what must have been a vast private tenancy arrangement. It was made up from one half of a converted eighteenth-century inn, located about 200 yards from the gates of the Woolwich Dockyard. It had no electricity, was lit by gas mantles and the only water supply was a cold tap with an earthenware sink housed in a lean-to addition at the rear of the building. It had an outside water closet 100 feet or so from the back door. The winters of the late 1940s were very cold and ice on the inside of bedroom windows was a normal feature. General heating was from a coal-fired kitchen range and infrequent coal fires in the hallowed ‘front room’ on special occasions. It was the time of smog before the Clean Air Act was introduced. The winter atmosphere was poisonous because the coal used throughout the district was of low quality. Serious chest infections were a mark of our lives and I live with the effects to this day.

There was an interesting moment when our electric public tramway system was finally dismantled. The roads on which the tramcars ran were paved with wooden blocks that were waterproofed and preserved by the liberal coating of coal tar. I assume now that the use of wood served to somewhat reduce the noise made by the steel wheels running on tracks at all hours of the day and night. The coated blocks were stripped from the road and left in piles by the pavement for anyone to retrieve as free fuel for that winter’s fires. It was a generous gesture and I made many wheelbarrow runs to satisfy my grandmother’s insistence that we should have our share. It was, I like to believe, the burning of this foolish bounty that pushed the legislation over the hill.

In the mundanities of day-to-day life, the lack of any realistic facilities combined with a young boy’s general reluctance made washing oneself an infrequent occurrence. However, a strict and unavoidable fortnightly Saturday night ritual was maintained. A galvanized tin bath, taken from its hanging place in the outside alleyway and placed in the kitchen in front of the cooking range, was filled with hot water from numerous kettles. Care was required to avoid burning one’s leg on the fire-side of the bath.

I paid dearly, mostly with embarrassment, for my lack of hygiene, particularly on one occasion when I was bent over in front of my whole class in a wintertime gym session and beaten with a slipper because my feet were black with grime. It was presumably meant to teach me to change my ways and was yet another example for me of thoughtless learning imposed at my grammar school. The sanctimonious middle-class teacher presumably had no idea that we had had no running water at home for many days and he probably would not have cared.

We were scheduled for rehousing under the slum clearance scheme but were very far down the queue. It was odd seeing the gradual disappearance of families and friends from around us, moved onto great new housing estates like those further out at Kidbrooke, perhaps only three miles away but, in reality, totally removed from all old origins. The well-intentioned rehousing broke the proximities and traditions of many families that had hitherto lived in the urban villages of the Dockyards and Woolwich Arsenal area for many generations in an atmosphere of retained Dickensian life

that was to be lost forever. Just across the road from my grandmother’s house there was a vast low-roofed open-fronted smithy where I frequently watched the giant of a leather-aproned man shoeing horses for the many brewers’ drays and Co-op milk carts that remained a vital element of postwar transportation. It could have been any rural village scene. I remember the drama of a horse slipping on ice at the top of the hill near my primary school and the milk-float crashing on to its side. There were hundreds of broken bottles and a deluge of milk on the hill.

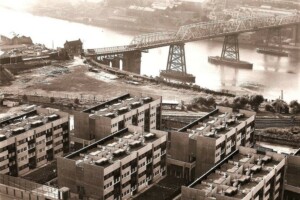

The old house was finally equipped with electricity in 1954, too late for us to have viewed the coronation of Queen Elizabeth the Second in the previous year even had we been able to afford a television. I was 13 years old when we reached the front of the rehousing queue and moved just a quarter of a mile up the hill of the milk-float incident into the second floor of a block of council flats. It was one of four 13-storey buildings perched on the slope. My mother, brother and I were placed in a two-bedroomed apartment and the council put my grandmother, then widowed, in a single-bedroomed unit with its front door exactly across the landing from ours; a small but

thoughtful piece of facilitation for continuing family interdependence.

Our flat had a bathroom with instant hot water supplied by a gas-heated Ascot boiler. The bathroom contained a lavatory (inside) and the hall and living room were heated by underfloor electric heating that drew power only in the night-time hours. The authorities had also provided a community laundering area with washing machines and driers for use by the residents of the four blocks, together with a play area with a charming little castle atop a brick-paved mound for the children to play in and be

safely watched. This alone transformed the humdrum and often brutal experience of the weekly wash-day for so many women, but my mother considered it inappropriate to have our linen on view for our neighbours to see. I was despatched each Saturday morning to the launderette in the centre of the town. It took me a good few weeks of boring rotational viewing before I learned that, for two-bob of my hard-earned pocket

money, I could pay the lady attendant to handle the process while I went off to the other new innovation, frothy coffee at the coffee bar where the young strived to be intellectual by playing chess.

As an odd aside, I learned to appreciate shiny, well-presented things. My uncle, an ex-professional artilleryman, taught me how to bull (polish) my school shoes until I could see my face in the toes; a habit that has persevered to this day. With this preference guiding me, I discovered that the hard matt-brown Marley tiles of the flooring throughout our new palace could also be polished to a mirror-like finish. It remained one of my tasks to maintain the gloss until I left home for marriage.

Mercifully, and at a very timely period of my life and the onset of serious puberty, I had become regularly clean and have never lost the delight found in the availability of instant hot water. It was a long time still before I discovered the added benefits of deodorant and that was only after a painful rejection by one of my first girlfriends.

Fifty years on, I visited, outside, the high-rise that propelled me into a more civilised and comfortable existence. The blocks looked rather forlorn and I vowed not to pass that way again. The slum clearance process was vital, but many good, less-damaged houses were swept aside along with those uninhabitable from war damage and neglect. Great historical neighbourhoods were bleached clean and deep family and neighbourly ties were severed.

There was, of course, an urgency of need but it is a sadness that, with more imagination and strategy, so much more could have been achieved and we might not now be seeing the relatively early dilapidation and destruction of so much of that post-war reconstruction.

If only the organisers of our lives could look farther over the horizon. It is after all only one life that we get. War and calamity may be unavoidable but slack thinking should be eschewed. The after-effects, like those of the great smog, blight the individual forever.