Council Estate Memories: Llanedeyrn Durre Shahwar

Share this

My experience of being working-class is a mixture of social housing and migration. My family was one of the last to benefit from the Right-to-Buy scheme that was finally abolished in Wales in January 2019.

I don’t remember the announcement of the abolition itself, or its coverage in the news, only my dad’s urgency that we buy the council house that we had been living in for the past nine years or so while we had the chance. He was very aware that this was our only chance to have a home that wasn’t temporary for the first time in nearly 20 years. Since we had moved to the UK, we had occupied five different houses, moving between government and Home Office authorities and local councils. The nomadic lifestyle is

less appealing when not pursued by choice but as a necessity to escape religious persecution and stay alive.

Today, I look out at my parents’ house and feel a sense of relief at being able to have a family home that belongs to us on official deeds and documents. Something I only realised that many of my peers had throughout their entire life as I got older. Yet still, that sense of relief is always accompanied by a mild anxiety surrounding ‘what if?’ scenarios where things go wrong. Things such as job losses, illnesses, political

tensions, Brexit and its ruinous social and economic effects on the UK, and on Wales in particular. I will never forget the months when we received notices about rent arrears in bold, red letters threatening eviction if not paid by a certain date. The working-class anxiety never quite leaves you.

When my family first moved into the house that we now own, we would find cat faeces deposited in our front garden for many months. This, accompanied by the disappearance of two doormats, and a ball thrown with such strength and intention that it cracked our living room window, made us realise that we weren’t quite welcome. I still often suspect that we aren’t. But at least such incidents no longer occur. At the time, Llanedeyrn was one of the least racially diverse areas in Cardiff, and still is, comparatively. Most BAME communities are populated in the centre of the city or by the docks, due to Cardiff’s trade and coal mining industry. Yet despite all this, my dad would continue to distribute Season’s Greetings and Christmas cards in December and sweets at Eid. Over time, we started receiving more and more cards back. Dad’s perseverance and the carrying on of South Asian neighbourly formalities had paid off.

Social housing and the Right-to-Buy schemes have received many criticisms over the years, usually from those who had the privilege of never needing to access such schemes in the first place. Regularly, the right-wing media, politicians and various public figures blame migrants for lack of available social housing. We grew up conscious of having to prove our worth through our contribution to society, as well as a heavy embarrassment. The demonisation of migrant communities is done with

misleading facts. Statistics published in 2015 indicated that 91 percent of social housing is allocated to UK-born citizens. In fact, most migrant families are likely to rent privately due to the high restrictions on who can and cannot access social housing. Even if migration was controlled, it would have very little effect on the issue.

For my family, social housing was the somewhat patchy safety net that allowed us to grow up, study, work and live. My siblings and I were socialised into a weird amalgamation of cultures in our formative years. We were regularly mistaken for being middle-class as we apparently projected supposed ‘middle-class values’. One of these was getting educated above the level of bachelor degrees at Russell Group universities, thanks to Welsh Government bursaries and scholarships. Such misconceptions and stereotypes about working-class families sadly still exist, but it wasn’t until a few years after university that I really became more aware of them. I

also began to realise the disparity between my peers whose parents were middle-class or from a working-class background like mine. There were kids whose parents would help them buy cars and houses in their mid-twenties and those who didn’t, and the class culture between the two was strikingly different. I had less world knowledge and experience to share. I only knew things I had learnt from books. Even among my working-class friends, I struggled to relate. None of them were helping their parents

to buy a family house for everyone to live in like my siblings and I were. Something that would always fill me with a sense of pride, jealousy and frustration all at once.

Even today, when I search ‘council house’ on Twitter, I come across many tweets in which it is used as a slur or an insult. It reminds me of how I was always conscious of sharing photos that would give away our area in the background and the weird displacement I would feel returning home from university to our council estate cul-de-sac. To drafty windows, creaky floorboards and leaky taps in a house that was too small for all of us, where we shared bedrooms even after the age of 20. To streets where smashed glass bottles on pavements would linger for years and to walls mismatched with creeping fungal invasions.

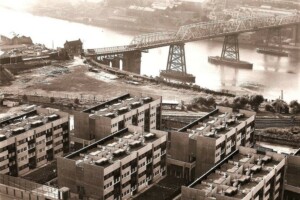

The bus back home would wind past all the posh mansions and bungalows before taking the exit on the roundabout that marked the beginning of our area with its distinctive council houses. I would sit and dream about the occupants of these red-brick homes that seemed so still, silent and closed off compared to our area. As a writer, I still unashamedly dream of living in one of those when my neighbour’s dog barks too loudly for too long or domestic arguments spill out into the street. But I think I would also miss the ‘hello’ nods of our neighbours every morning and the Christmas cards.