Council Estate Memories: Hartcliffe Paul Smith

Share this

For my parents, being allocated a council flat in the 1960s was a huge achievement. It symbolised security and independence. Being nine-months old at the time, I wasn’t aware of its impact.

My mum and dad had both grown up in council housing; my grandfather had been involved in building it during the post-war boom. Growing up on a council estate was just the norm for me, as all the relatives we visited also lived in such areas. My dad’s parents lived in Knowle West, built in the 1930s, and my mother’s parents lived on another, smaller estate in the Cotswold town of Winchcombe. Until I went to secondary school, pretty much everyone I knew was a council tenant. It didn’t occur to me that we were separate or stigmatised or anything other than typical.

It seemed that the council ran almost everything and determined everything: roads, open spaces, colour of front doors, schools and youth centres. There was a doctor’s house across the road, which was just a larger council house, still owned by the council, and the priest for the church next door to our flat lived in a council flat in one of the tower blocks. The council even helpfully placed a post on the rectangle of grass outside our flats with a sign saying ‘No ball games’. It made a great goalpost, as did the strategically placed trees at the two ends of the ‘pitch’.

Two things happened when I was 11 that were of huge significance: we managed to exchange our flat with an elderly couple who had a house in the same street and I started at secondary school.

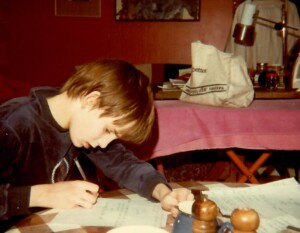

Living in a flat had restrictions. The first was we were always being told not to run around and disturb the elderly man who lived below us. The coal bunker was downstairs in the garden and the garden was shared. In a house, no-one was underneath us, the coal bunker was actually within the house (when we were converted to electric heaters, it became a little office), and the garden was all ours. It also meant my brother and I could have our own bedrooms. The garden was enormous and completely overgrown – excellent for dens – until over time we took control of it.

Going to secondary school introduced me to people who didn’t live in council housing; they owned their own homes. It was here that the class divide started to become clear. Many kids from Whitchurch looked down on those of us from Hartcliffe and they didn’t mix much with us Hartcliffe kids after school hours. On reflection, whenever I was with teenagers from Whitchurch it was in Whitchurch or in town, never in Hartcliffe.

The subtle and not-so-subtle stigma about living in council housing created a certain amount of siege mentality and Dunkirk spirit that developed into a pride in the area and a sense of identity. For some – not me – this developed into a gang culture that was played out in fights with the neighbouring estates of Knowle West and Withywood. Anyone from outside the area wouldn’t be able to tell you where Hartcliffe ended and

Withywood began, but we knew. These rival gangs would come together at Ashton Gate to fight similar gangs supporting other football teams. This sense of siege became greater in the summer of 1980, following the St Pauls’ riot. Most days, a riot van was parked near the shopping centre. Clearly, Hartcliffe would be next.

The media would often describe Hartcliffe as an inner-city estate (it’s five miles from the centre of the city) and even a ‘no-go’ area. But it never felt dangerous or unsafe to walk around, and the contrast between the media portrayal and the reality was huge. Being on the edge of the city meant that it was only a short walk into the countryside and the estate itself was very green with plenty of open space.

At 18, I left Bristol to go to university. In some ways this was an escape; in others it became an assertion of identity. Within a year, my circle of university friends was mainly comprised of similar working-class refugees who gravitated towards each other in what was a largely middle- and even upper-class environment. (There was an agricultural school at university where the ownership of acres seemed the entry qualification rather than A levels.) We didn’t quite fit in there, and when we went home we didn’t quite fit there either. At university we felt looked down on; back in the estates

we would be accused of having ‘posh friends’ and not wanting to mix with the ‘likes of us’. As estate undergraduates (‘estate’ meant something different to the agricultural students), our identification with our home areas became stronger. When people asked where I was from, I would say Hartcliffe first, Bristol second.

Returning home after university, I was selected to stand for the city council representing a ward that included about half of Hartcliffe plus some of Whitchurch.

It was as a councillor that I came across the initials NFH – Normal For Hartcliffe. It was a code used by social workers and doctors to describe the conditions of children in the area. What would be unacceptable in other parts of the city was NFH. Poverty, poor health, abuse and neglect could all be explained away with three letters. It’s not clear if it meant that these things were of no concern and that NFH was just a professional shrug of the shoulders, or whether it was a call to action. I suspect the former.

It’s almost impossible to write about growing up in the area without a reference to the riot of 1992, although some people hate it being discussed. That year, local professionals and community activists had been working on the latest regeneration-programme funding-bid, this time called City Challenge. The estate had been visited on a lovely sunny day by government minister Michael Portillo and a gaggle of civil servants. Portillo had a tour of the estate and said ‘it’s quite nice here’. That was the death of the bid. The greenery, trees, all in the shadow of Dundry Hill, meant that the area could not compete with grimy, boarded-up, litter-strewn inner cities. By tragic

coincidence, the day the official announcement was made, the police killed two youngsters from the estate in a botched recovery of a stolen police motorcycle. That night, some of the estate’s usual suspects piled out of the pub and headed for the library at the top of the shopping precinct. Part of the library was a ‘cop shop’, a drop-in office used by the police. The crowd torched it and then started on the rest of the shops. The police showed up, there was a bit of a standoff, it started raining and everyone went home.

The report of the incident on the media the next day – along with the helpful maps – brought everyone looking for a fight with the police from an 80-mile radius to the area and a full-scale riot with petrol bombs, riot shields, police charges and helicopters. Unlike a terraced inner-city area, the semi-detached homes and large gardens of Hartcliffe meant that the area was permeable and much harder to contain rioters, so the damage and activity were spread across the estate. The next night, the police

presence became huge and the riot was over.

What followed was a new focus on the area leading to the building of the Gatehouse Centre; a building incorporating business workshops, employment training, crèche, café and community spaces. The building of the shopping centre followed more than a decade later.

I also took some time to research the history of the area. I found the original plans in the city archives. Here I could see all the proposed facilities that were never built; the cinema, the cricket pavilion and the network of youth facilities. While Bristol and Somerset councils haggled over who would get the estate, the city council’s boundary was extended to incorporate it, the ambition of post-war reconstruction diminished and, as the money became tighter, the quality of the homes also deteriorated, with

brickwork replaced by concrete.

I moved out of Hartcliffe in the late 1990s. I was, and am, opposed to Right-to-Buy so I didn’t make a killing from the cut-price deal available. Within a short time of moving out, the new tenants bought the house and built a wall with stone lions on the gateposts.

Today, I still feel that Hartcliffe shapes my identity and character. I still feel huge affiliation and loyalty to the area. I was angry earlier this year when once again a BBC presenter saw the area as fair game for misogyny and sneering middle-class disdain for working-class people in a ‘humorous’ song. (A parody of Blondie’s ‘Heart of Glass’ about a promiscuous woman from Hartcliffe was performed on local radio in a mock-Bristolian accent.) The area has changed. The trees planted when I was a baby are now enormous and dominate the gateway into the part of the estate where I grew up. The new shopping centre has removed the burnt-out buildings but replaced landscaped rose gardens with an almost empty concrete car park. However, in essence, the area has changed very little. In some ways, nor have I: just older, greyer, slower and hopefully wiser.