Council Estate Memories: Gateshead David Olusoga

Share this

If the intention had been to mark out certain children and to ensure they were subjected to ridicule and bullying, then our teachers would have struggled to come up with a better system.

Had they set out to make the hierarchies of wealth and social class among the children under their care obvious and evident they could hardly have devised a more precise and subtle ritual. I don’t know why they did it. I suspect it was nothing more than thoughtlessness and adherence to an old practice that no one had ever thought to question.

The ritual took place on the first day of each academic year in my redbrick junior school, high on the hills above the River Tyne in the town of Gateshead. On those late autumn mornings, after we had been ushered from the assembly hall, we were dragooned into our new classroom. There we were each allotted a little wooden chair and placed behind a square wooden desk – objects of antiquity that had little indentations in which the inkwells of our Edwardian predecessors had once rested. The desks were arranged into neat, regimented lines in front of our new teacher, who would hush the class and open the new register. My hands would begin to tighten into fists and I would start to feel a cold and sickly form of anxiety. Among my multiple fears was that my voice would creak or that when I spoke other children would openly and immediately laugh or mock, rather than waiting for a later opportunity. With head down and ballpoint pen poised above the grid-lined pages of the register our teacher would read out the names of each child then, with one word, demand that we divulge

the information that revealed everything that I wanted so much to conceal – my family’s poverty. The wounding question came in the form of a single word – address?

When it came to my turn I had to divulge not the name of a street, road or an avenue but something called a ‘walk’; an ersatz street, a ‘street in the sky’, the planners had called them. A ‘walk’ on a vast, sprawling, ugly, deprived, densely populated and widely reviled council estate. A sink estate, a place in which, it was universally presumed, no one would live unless they had no choice. This I had to divulge in front of my whole class, my enemies and the bullies.

The children who lived in the better streets of our declining little town, children whose parents had jobs that enabled them to perhaps afford a second-hand car, did not fear the first register of the school year. For them memories of this little ritual have probably faded. But poor children are acutely aware of the minute gradations of poverty. Just as the children of the wealthy calibrate one another’s status by learning to decipher the back-stories told by the cars in which parents drop their children off at

boarding school, those of us at the other end of the scale knew how to precisely calculate relative poverty. We were acutely aware of what we were and what we were not, what we had and what we lacked, and we could read the signs; hand-me-down clothes, plastic shoes rather than leather ones, school trips suspiciously missed. Those just above the poverty-line live in close quarter with those below it. They know intimately what poverty looks like and they know its address.

In our school in the 1970s, and again for reasons that have more to do with thoughtlessness than vindictiveness, another marker of poverty was literally pinned to the chests of the poorer children. As if we were being marked out as social undesirables or degenerates by a totalitarian state, those of us from families deemed poor enough to qualify for free school meals had our meal tickets attached to our shirts and jumpers with safety pins, to prevent us misplacing them. Those little grey and red tickets advertised our poverty to everyone – other children, their parents, the teachers, the dinner ladies, the lollipop lady who ferried us across the road and through the school gates. When that indicator was combined with the publicly declared fact that I lived on a council estate infamous for its deprivation, my lowly status was clear to all. A council-house boy on free school dinners.

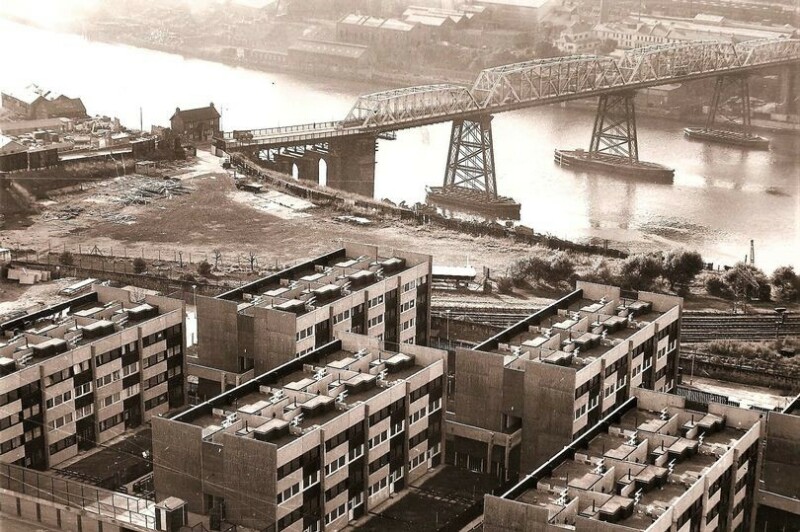

When I look now at the few grainy black and white pictures that survive of my council estate it looks like something from the other side of the iron curtain. The Soviets called developments like it ‘Khrushchyovka’; cheap prefabricated concrete homes built to house those with nowhere else to go, named after Soviet statesman Nikita Khrushchev. In the USSR these bleak rectangles of concrete, with their small windows and dark stairwells, were presented by the state propaganda apparatus as a temporary stopgap. They were vertical prefabs that would be replaced with more palatial homes the moment Russian communism reached its ‘mature stage’ and the workers’ paradise had been realised. Many of them are still standing. In Britain there was never any pretence of impermanence. The estates were the solution to the slums of the nineteenth and early-twentieth century. They were their direct replacement, often built on the land on which they had stood. They were the future, not some staging post on the way to it.

The Victorian slums had been known as ‘rookeries’, ‘hells kitchens’ or ‘devils’ acres’. When they were cleared in the twentieth century, a new argot was devised by the planners. Mass housing built for the poor was arranged into ‘estates’. A strange word to choose. The Americans were more honest. Their council estates are known as ‘projects’. In Scotland they are called ‘schemes’, the people who live on them ‘schemies’. Both words hint at the idea of civic action, the verb in the ascendant. In our town, as in others, the planners took things one step further. Although everyone understood that my home was on an ‘estate’, our grey blocks of social housing, made

of prefabricated concrete slabs assembled on the banks of a then polluted industrial city, were officially known as a ‘village’. Fourteen horizontal blocks, like towers laid on their side, homes for 3,500 people constructed at a cost of £3,700,000. They represented the apotheosis of the career of the Borough Architect Leslie Berry, the final flowering of his ‘village community idea’. Berry’s concrete village was self-enclosed, with its own shops and even a ‘village hall’: a windowless brick square as unlovely and unloved as every other aspect of the whole dismal project. One of the old Victorian

terraces that had been demolished to make way for the new estate had been known as St Cuthbert’s Terrace and so Berry’s urban village was given the name St Cuthbert’s Village.

There is a series of photographs of Harold Wilson, the Prime Minister who prophesised how the ‘white heat’ of technology would transform Britain, on a visit to Gateshead in April 1970. Laid out on a table in front of him, in one photograph, is a scale model of St Cuthbert’s Village. Flanking Wilson is the lord mayor and the local councillors, the men who had convinced themselves that the new estate was the solution to the old slums. In another photo Wilson is shown pulling a cord that opened a pair of small

velvet curtains and revealed a plaque that recorded his official opening of the new estate. Within just a few years of that official opening St Cuthbert’s Village had become a new slum, itself in need of clearance. Twenty-five years after Wilson’s visit all but one of the blocks, and the ‘walks’ that connected them, were demolished, including my childhood home.

During the hottest weeks of the hottest 1970s’ summers I spent living in St Cuthbert’s Village, the foundations of the old terraces that had been demolished to make way for the estate could be seen as brown lines of dry grass. Other than those ghostly traces there was nothing to suggest they had ever existed. I don’t remember when I first learnt that living on a council estate was shameful, but that sense of shame wasn’t unique to me or my generation. The people who had lived in those terraces knew that

same stigma. Many of the children who had lived out their childhoods in those houses had attended the same Victorian school I had gone to, and sat in the same square wooden desks, where they too had been made to divulge their addresses to earlier generations of teachers and school bullies. The stigma of the old slums had, by some unknown mechanism, been transmitted to the new estates and the inhabitants of the new concrete slums, almost as if the soil itself had been contaminated. The stigma remained potent because within its DNA was another feature of the Victorian past, the lingering belief that poverty is evidence of moral failings.

That I can recall, four decades later, my feelings and my shame about living on a council estate testifies to the potency of this stigma. Yet from the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century I look back at our prefabricated home in our concrete village and realise that we were, in a sense, fortunate. In 2019, families like mine, with little money and few options, are not given homes on council estates. They are placed on waiting lists that never shrink. Instead of life in a damp concrete apartment, they spend years in privately rented B&Bs. Some live out much of their

childhood in conditions closer to the slums of the nineteenth century than the estates of the twentieth. The challenge that planners and experts should have spent the past four decades addressing was how to rid council estates of the stigma that had become attached to them. They could and should have spent those years asking themselves how it is that in other European nations social housing is both well-built and popular? But those questions were left to the academics, as the supply of new social housing was cut off by political edict pitilessly pushing the people for whom such homes are needed to the margins of society.