Council Estate Memories: Frome Xan Brooks

Share this

At the age of nine I bundled my belongings in the back of my mother’s second-hand Citroën and we barrelled out of the city for a fresh start in the west. What an adventure this was; I could barely contain my excitement.

At our backs was a tumbledown South London house that we had struggled to sell (officially due to subsidence, although this was estate agent code for being in a predominantly black neighbourhood). At our fronts was a tumbledown Frome cottage we finally couldn’t buy (the survey said the whole place was on the brink of total collapse). So we were out in the world, my mum and me. We were winging it, roughing it, living on a prayer. Council housing was the net that caught us as we fell.

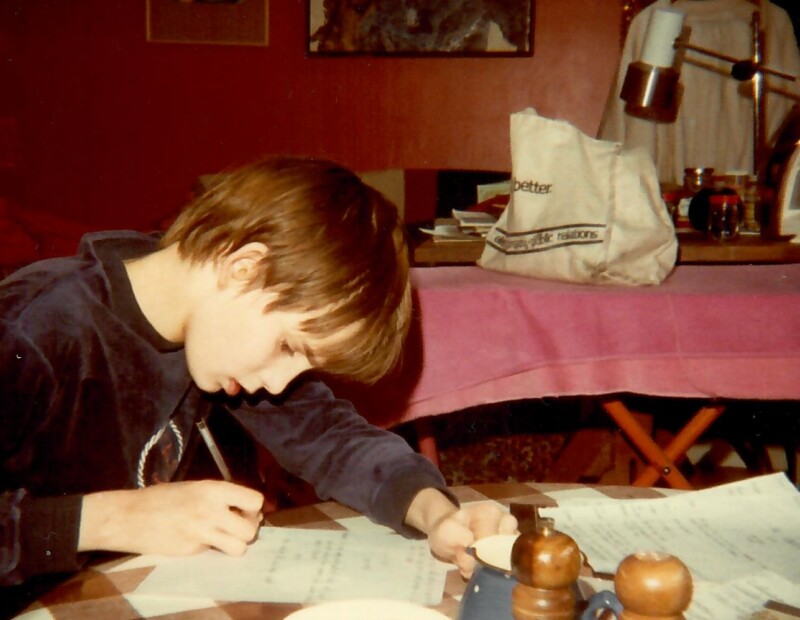

Kids live in the moment. All we see are the details and we’re liable to misconstrue even those, reframing them to fit a narrative which bears only a passing resemblance to the truth. My life at the time felt curiously thrilling but entirely safe. If someone had pointed out that I was temporarily homeless, I would have hastened to set them straight. Of course we weren’t homeless, we were simply between homes, crashing for a few months in the downstairs corridor of a friend’s house in Somerset. If they had said we were poor, I’d have corrected that too. I had food to eat, books to read and a brand new asthma inhaler to suck on; all of which proved that we were doing fine, thanks. Insofar as I even considered such matters, I regarded my mother and me as wealthy, dashing adventurers; a welcome addition to any humdrum country town. Others – the majority – saw us differently. To them we were a head-spinning disaster, a burden to society. The jobless single mum and her skinny, sickly son.

What’s clear to me now is that we had pretty much bottomed out. We spent three months sleeping in that downstairs corridor. We had insufficient funds to purchase a place of our own. One Friday in December 1979, my mum’s plan was to collect me from school and then drive north through the weekend because she had heard that there were houses that way you could buy for £10k. Sometimes I wonder how this last trip would have gone. It may well have been an adventure too far. But it never happened because that same day she was shown what the local authority referred to as a ‘housing unit’ on the outskirts of Frome. ‘It’ll do us for six months,’ she told me that night. We wound up living there for the next five years.

As it happened, our grand arrival in the winter of 1979 coincided with the high-water mark for council housing in the UK, when more than 40 percent of families rented their homes from the state. Not that I was aware of this at the time. Not that I was even entirely certain where this house had sprung from. We needed somewhere to live and, hey presto, here it was. That was how British society worked in those days. The government looked after drunks, little children and cash-strapped single mums.

Besides, these weren’t the Brutalist council blocks of popular imagination but rustic bijou buildings recently saved from demolition. The housing unit turned out to be a customised Victorian stable, so small that school-friends used to joke that I slept on top of the cooker. From there we moved to a converted weaver’s cottage, part of a larger estate of low-income housing up by the old print-works. The neighbourhood was a grid of picturesque terraced houses. It could have provided the backdrop for a period movie.

At the Victorian stable I’d propped a stepladder against the garden wall so as to more easily visit the children who lived in the house behind. I did not do this at the weaver’s cottage. Next door lurked the Gallaghers, who had a reputation as the worst family in town, a band of bawlers and brawlers, constantly in and out of the nick. And yet either the Gallagher legend had been inflated or the walls were so thick that they dampened their volume, because in all the years we lived there we barely heard a thing. The only occasional nuisance was Gallagher Sr, the man of the house, who had a habit of coming home drunk of a night and mistaking our house for his own. On finding his key wouldn’t fit, he’d hammer at the door, demanding to be let in. He once pushed past me without a word and set himself down in the armchair by the telly – at which point it felt almost rude to ask the man to leave.

It would be nice to report that our troubles instantly ended the moment we were scooped up by the council – except that this would be a sugarcoated lie. Gradually, as I grew older, I came to see us for what we were: not a pair of glamorous swashbucklers but a single-parent household on benefits, struggling to make ends meet in what was then a fairly conservative, traditional town. Life, I grew to realise, was not exciting but scary. We had no money, we had few prospects. But it wasn’t all bad because what we had was a house. Pretty much everything in my childhood had turned out to be precarious, liable at any second to be blown away like topsoil. But this was okay because what we had was a house. It was there in the morning; it was there every night. And today, looking back, do you know what strikes me as the most quietly miraculous aspect of that chaotic, anxious time? The fact that the house was never an issue. The fact that I was able to take it for granted.

If (as has been exhaustively documented) a privileged background provides an air of entitlement, it follows that a disadvantaged one fosters the opposite. Insecure childhoods breed insecure adults. Lack of opportunity becomes our natural state. Even assuming we do well for ourselves – even assuming, against the odds, that we land the posh jobs – we’ll most likely suffer from impostor syndrome. We fret that we’re unqualified, illegitimate and about to be rumbled. We stare at our payslip and wonder if we’re really worth it.

Too much insecurity, in other words, can hobble a person for life. But a single foothold can prove invaluable. That’s what council housing was for me. It provided the foundation that might be used as a springboard. It made me proud of my status. It helped me to like who I was.

Relatedly, I think, council housing lifted me out of one family and made me part of another. No longer was I some rugged, inhaler-wielding individualist, riding shotgun with my mother, somehow outside of society. Now I was a member of a wider community: the council-house generation, the underdog crew. We were raw and untested and newly empowered. We went at things our own way, freestyle, like Saul Bellow’s Augie March. And we figured that if decent housing was a birthright, well then, guess what, a decent job might be, too. Yes, the door is shut to the likes of us. Our key doesn’t fit, probably never will. So bang with your fist until someone opens up. Sit yourself in the big armchair. Dare the bastards to throw you out.