Council Estate Memories: Downderry Natasha Carthew

Share this

For me, growing up in a council house in Downderry, Cornwall, meant I was part of a community that always had my back; an extended family who relied on each other to babysit the kids, or to lend you that elusive 50 pence for the ‘lecky’ meter until my mum got paid from one of the many local cleaning jobs she worked.

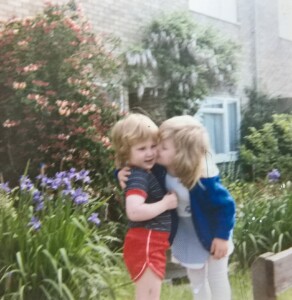

As kids, we always had a group of friends to head down to the beach with in summer (our estate was 100 metres from the sea) or up to the fields and woodland where we made camps in the trees.

It was important in those early days to not only be a part of the community, but to also be a part of something that was secure, permanent and protective; the things that getting a council house meant to my mother, sister and myself. It was a place that we could call home without the threat that we would be asked to move on at the whim of a landlord who needed the space for holidaymakers at ten times the rent.

The security that came with obtaining our house was huge but getting one in the village where my family had lived for generations was even bigger. We were a proud family and proud of our Cornish name. Everyone knew us in the village and we knew all of them. The possibility that we might have had to move to another community or a town would have been heartbreaking for us. This is why I know first-hand why council houses are so important and why they should be available to those who need them: not just people who live in poverty, are homeless or living in sub-standard conditions, but also those whose identity and culture are entrenched in the countryside but who cannot afford to live there.

Rural areas have proportionally less affordable housing than urban areas (many villages lost most of their social housing when council housing was sold off and not replaced); only eight percent of housing in rural areas is classed as affordable, compared to 20 percent in urban ones. Add to this the fact that rural wages are on average lower than those in urban areas, and it’s obvious why rural communities are facing a crisis. The average age in rural communities is rising as young people and families are being priced out. To keep our rural communities thriving, we urgently need to protect the affordable homes already built and to make sure they don’t get sold off as holiday homes. The gap between average wages and average house prices is growing faster. In addition, it takes longer and costs more to build social housing in villages than in cities and large towns. We need to demonstrate the positive value of housebuilding in rural areas, and to show how building affordable housing is helping rural communities to survive and thrive.

Our countryside is in the grip of a housing crisis. In over 90 percent of rural local authorities, average house prices are more than eight times higher than average incomes, while a single person on an average rural wage can expect to spend 46 percent of their income on rent. To seriously tackle this rural housing crisis, planners need to build more small-scale council estates that will empower rural communities and help them succeed for generations to come.

I still remember that first day our mum collected us from school and told us the keys to our new home were ready. The moment she opened the door, we flew in to skid on our knees across the linoleum, followed by half a dozen kids from the estate. As a young child, I was yet to witness the stigma of social housing; that came a few years later when I had to catch the school bus to travel ten miles to secondary school in the nearest town and was called ‘council house trash’ for the first time. School was a place where kids were divided into the haves and the have-nots; the kids who came

from rich houses and those like us. Although some kids called us trash, you could always tell it was really their parents that you could hear talking. The few of us who came from our village council estate were on free school meals and that meant the walk of shame every lunchtime to the front of the dinner queue. Kids from all over our corner of Cornwall who lived in and around the edges of poverty stood like outcasts in a Dickens novel. But in those moments, we as a group became stronger, fortified with the knowledge that there were many like us and our sense of community grew into a feeling of pride that came from being a bit different.

Insults about those living in social or council housing will always be thrown around; sometimes they will stick. However, this housing provision is not a simple case of deciding where poor people should be put. It is about where people who can’t afford to live in this increasingly capitalistic, covetous country would actually be happy, live heartily and thrive.

In rural areas we will always have that additional problem, the growth of second-home owners, rich folk who have bought up every available small miner’s or fisherman’s cottage to holiday in maybe once or twice a year. This has not just ripped the soul out of our villages but has also taken away affordable homes from those who really need them. Add this to the fact that nearly every council-built house is now privately owned, and I fear families such as my own have been completely pushed out of their communities.

Council housing is important because it is secure housing and, for kids like me growing up, that meant safety, community and a place to be free and to dream of a future that was not bogged down with the uncertainly of inflated rents, or the worry of having to leave my home village behind for good.