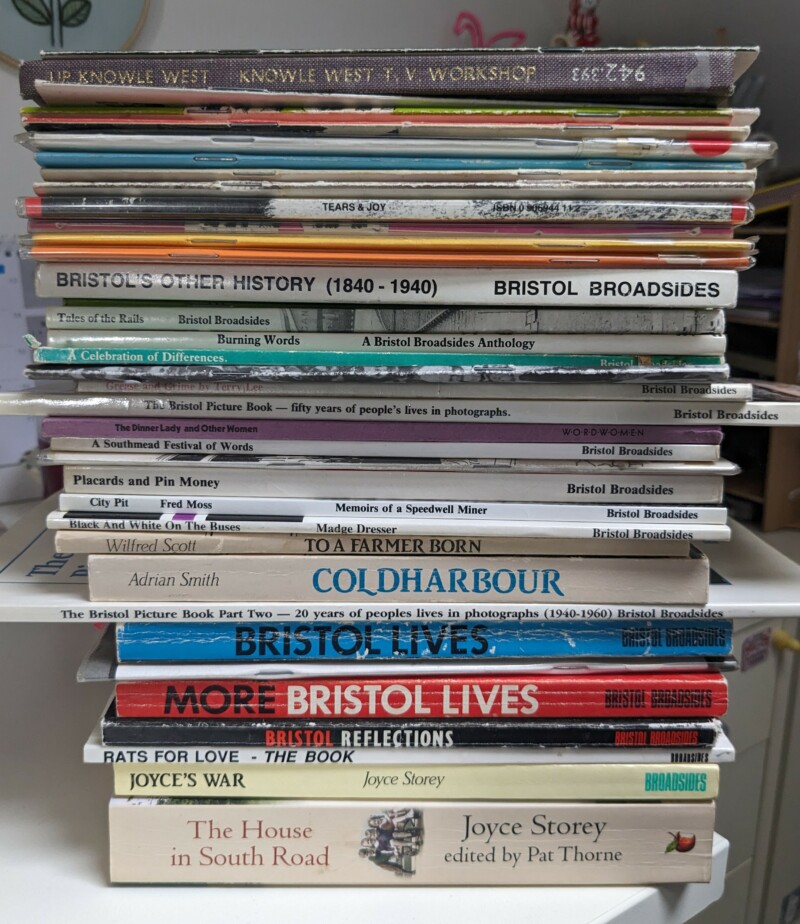

Bristol Broadsides: 1976-1991 Jane Duffus

Share this

INTRODUCTION

‘Bristol Broadsides … one of the most valuable organisations currently working in the city.’ (Bristol Evening Post, 23 June 1988)

The early-1970s were a time of historical uprising. Working-class people were standing up to the idea that their stories were not worth hearing. They were also rebelling against sex pay discrimination and trade unions were at their height. Meanwhile, the Women’s Liberation Movement and Black activism were gaining momentum. And these collective feelings of disquiet were demonstrated most clearly in the arts: punk music, anarchic fashion, the rise of working-class writing. In this way, Bristol Broadsides, established in 1976, was an important part of the national scene of community publishers in the UK.

Although Broadsides was based in Bristol, the story began in London. Ken Worpole began teaching English at Hackney Downs School in 1969. Alongside teaching, Ken was involved with Centerprise in Hackney, opened in 1971. This grew from being a co-operatively run radical bookshop and café to including an adult literacy centre and a publishing project, focusing on writing by working-class people.

Ken says: ‘For a brief period, Hackney Downs, which was largely still made up of traditional, rather conservative, male teachers, suddenly had a number of new people who wanted to bring in new ways of thinking about the relationship between reading and writing in the classroom, in this case young boys who had problems getting engaged with literature. [Remedial teacher] Ann Pettit and I began to produce reading materials inside the school based on their experiences. We recorded some of the children and turned them into little booklets.’

Ken was also involved with helping to set up the Federation of Worker Writers and Community Publishers in 1976; Bristol Broadsides was an early member. It was through the Federation that most community publishing groups gained a sense of what people were doing in other parts of the country. Ken says: ‘The Federation quickly became the mothership even though it didn’t have a physical headquarters. But it had some very charismatic people from the different parts of the country. And this, for a lot of people, was the first time they’d ever been to Manchester or Newcastle or to Hackney or to Liverpool or Bristol.’

Ian Bild was one of Ken’s pupils at Hackney Downs and found Ken’s work inspirational. He would often go with Ken when he was interviewing people in Hackney. Ian says: ‘We would tape record local people, because the history of Hackney and the history of London up to then was seen as the history of kings and queens, the wealthy and business people and all the rest of it. The lives of so-called ordinary people were effectively ignored. This was a completely new aspect to ways of looking at history.’

Ian adds: ‘Now things have changed radically. But then you didn’t really get much of the lives of ordinary people working in factories or schools or hospitals or whatever. Through our writers’ workshops we came to understand that many people were writing, and they were just putting stuff into drawers and saying, “Well, that’s not important, that’s just scribbling”. But actually a lot of the stuff was really good and interesting. Fascinating in its own right. We were trying to democratise both the creative process and the way we look at history through the writers’ and history workshops that we were setting up.’

The workshop format was a new way of teaching, eschewing the traditional idea of an “expert” standing at the front and talking to the silent room, instead creating a forum for people to share their experiences and learn from one another.

Ian took these ideas with him when he came to Bristol for university in 1974, where Ian and his partner Uta took a room from Colin Thomas whose house was ‘a hotbed of radical activity’. Colin was making documentary films with the BBC but felt frustrated at the limitations the big corporation imposed, explaining: ‘I made a film with the Bristol Trades Union Council. The narration for that was researched and written by members of the Trades Council. And I suppose that was an offshoot of the kind of area that Broadsides was developing, where you gave people a voice, you didn’t tell them, as so often one was doing in the BBC. You gave people a voice.’

1976

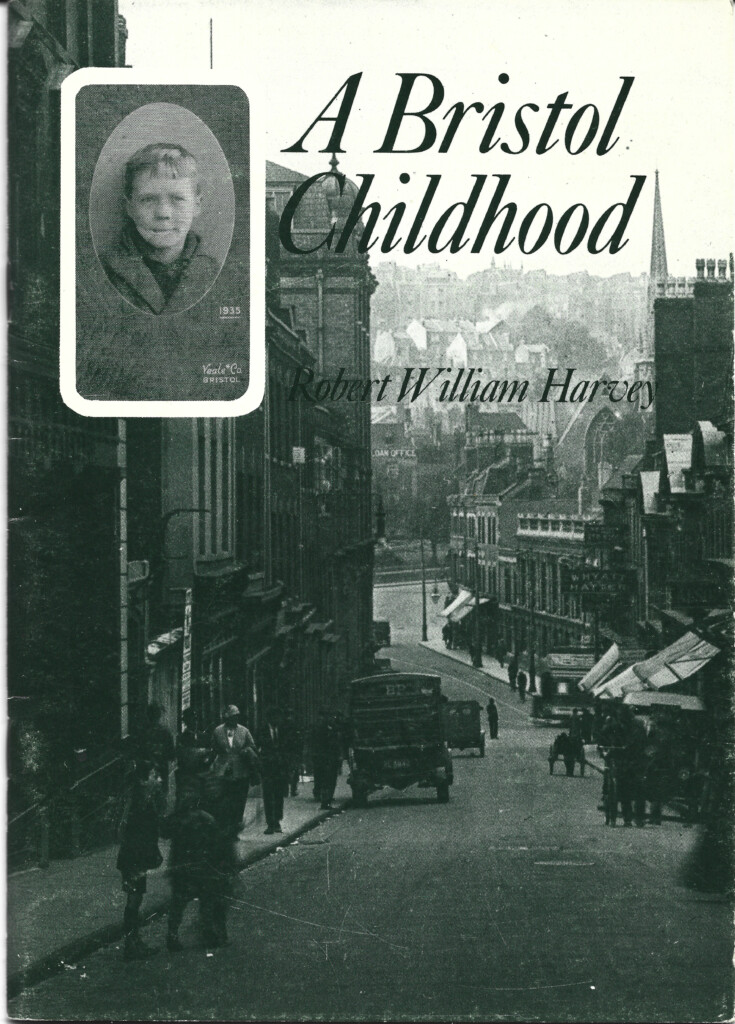

Through Colin, Ian met David Parker: a tutor organiser with the Workers’ Education Association (WEA), who was equally interested in capturing the stories of real people. David had come to Bristol in 1973 to work for the WEA and was based in Knowle West and Hartcliffe; areas known to have an educational disadvantage. He came across a Bedminster man called Robert William Harvey who struggled with literacy so, with funding from the Adult Literacy Resource Agency (ALRA), David helped Robert improve his reading and writing. The outcome was A Bristol Childhood, unofficially the first Bristol Broadsides booklet, and it led to further money from ALRA to enable volunteers to work on a 1:1 basis with other adults who needed support with their literacy skills.

1977

With his university degree in his back pocket, Ian called a meeting in Colin’s house for likeminded individuals looking to set up a worker writers’ publishing project. The name Bristol Broadsides was selected, inspired by the broadsides that were published in earlier centuries to share radical information. Ian says: ‘We formally set up a co-operative to deal with the growing work.’ David adds: ‘We all wanted to hear the voices of ordinary people in different sorts of ways.’

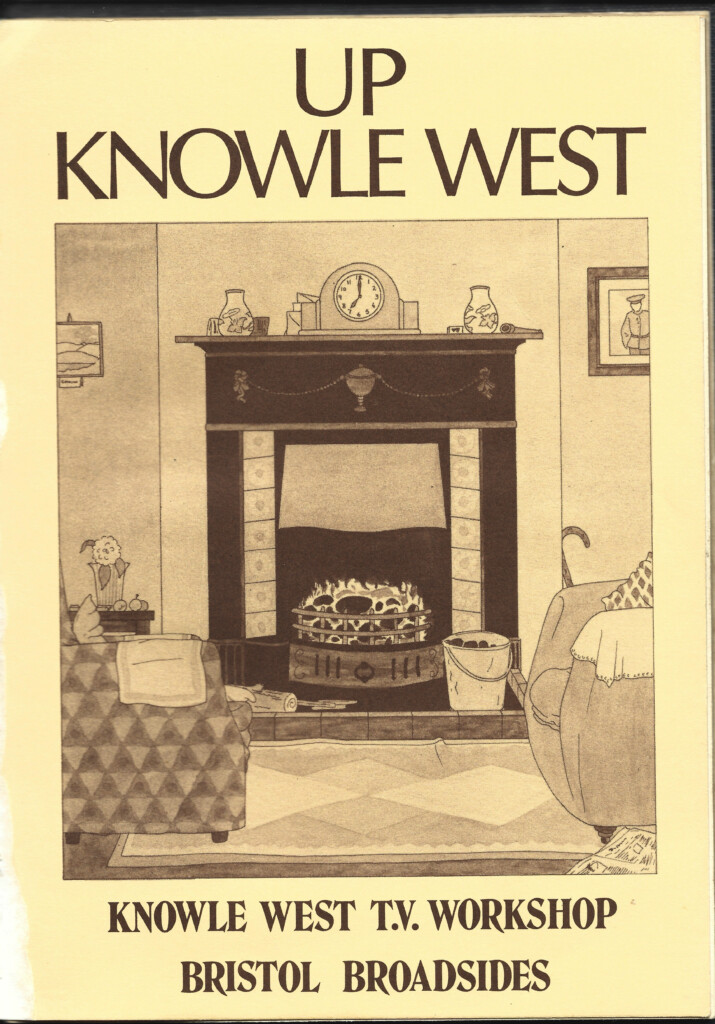

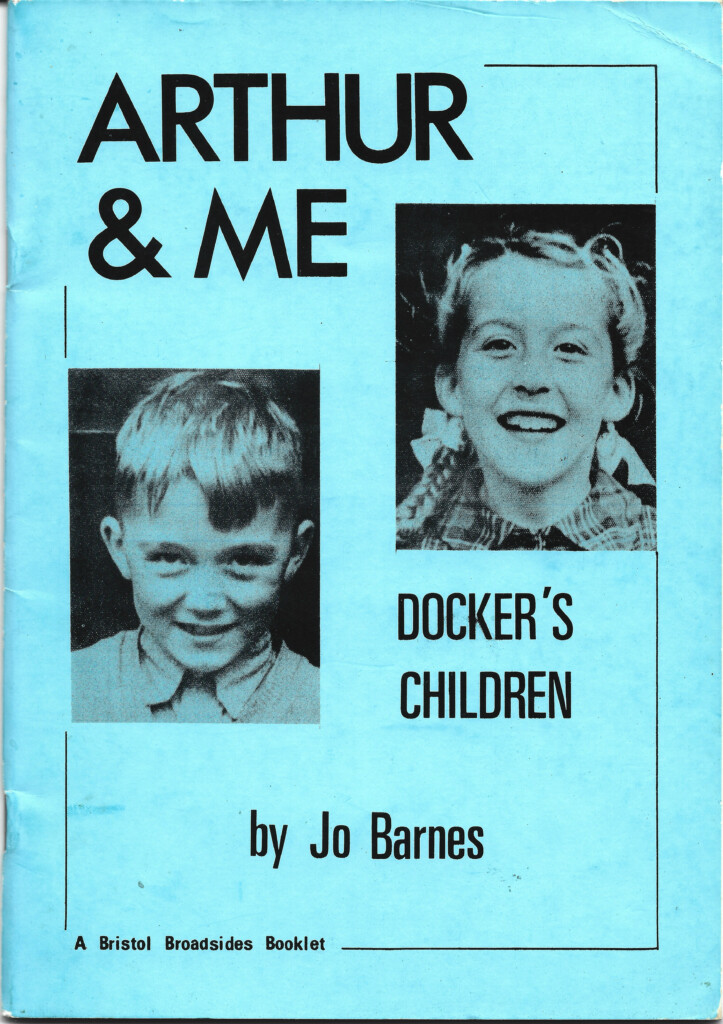

At the same time, Colin was interested in a small cable television station in Knowle West called the Bristol Channel. One of the women who was involved in contributing to these programmes was Pat Dallimore. ‘She was totally inspirational in all this,’ says David. ‘She was a gifted, uneducated, working-class woman who grew up in Knowle West. She was married to a guy who was a docker. She fostered a number of children, had her own children, too. She lived at 14 Allard Road, I still remember her address. And she was a natural. She was witty. She was creative. She could write poetry, she could write prose, she could talk.’

Ian explains: ‘We coordinated what people were doing already and could give value to what they were doing by publishing their work. And then there were big debates about quality and who do we publish and why do we publish?’ How would those choices for what to publish be made? ‘In Knowle West, the criteria was simply that people were writing and that was actually enough. The quality was very mixed. Some of the writing is absolutely brilliant. And some of the writing is not really very good at all. But we were publishing it because we wanted to encourage people and give them a voice.’

An early document was drawn up outlying some suggested principles to remember when considering something for publication by Broadsides. These included: the writing must be by working people (preferably manual trades); the text should be informative to readers; the texts should be chosen democratically; and the books should be brief to keep costs down.

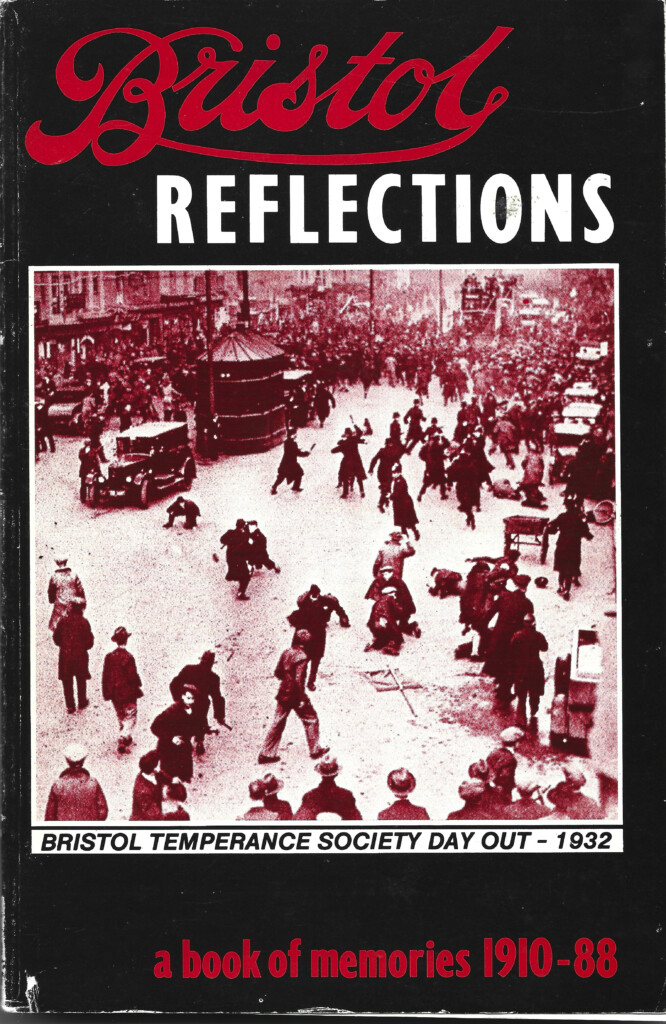

There was interest from some academics, too. For instance, Dr Madge Dresser from the polytechnic was involved from day one. Stephen Humphries was doing a lot of work on radical childhood. Later on, Dr Myna Trustram would join Broadsides and develop her research into working conditions in East Bristol. ‘There were huge debates within the academic history world about the value of oral history,’ says Ian.

The issues of class, race, feminism and so on were central to the work of Broadsides. ‘You couldn’t get away from those discussions,’ says Ken. ‘It was very painful for some people. Some of the writers’ groups, which were very strongly working-class, would say something about “Why are gay people here? They’re not working-class.” And that’s the discussion you have to have. Or “Women aren’t necessarily working-class”, all that. You have to keep coming around to it. I don’t know why or how we were so successful in holding everything together because these were clearly very, very difficult discussions.’

Madge adds: ‘The early days of Bristol Broadsides were marked by some suspicion towards people like me who came from a middle-class background and who thought that gender politics were important at the time. And subsequently Laura Corballis [a future Broadsides co-ordinator] suffered quite a bit from that. But really we were just trying to provide an alternate vision of Bristol’s past and give support to worker writers.’

A call for new voices in literature had started in the 1970s, in schools and adult education, and this led to a need for new teaching materials. ‘There was a tremendous early enthusiasm for publishing voices that had not been published before. And there was money to do this,’ says Ken. ‘The regional arts associations were pretty sympathetic. And publishing was becoming easier. You could do it yourself more or less. When we started, we were just into offset litho. Previously, we would have to pay a typesetter to typeset everything in hot metal type. The technologies of publishing and tape recording just became easier, it was very exciting.’

Bertel Martin, who would later become chair of Broadsides, initially became involved as a member of the Easton Writers’ Workshop:‘I’d say a lot of community development can end up being very arrogant. It can be about giving arts to people who they think don’t normally have art. Whereas with Bristol Broadsides, it just gave people a space to express themselves.’

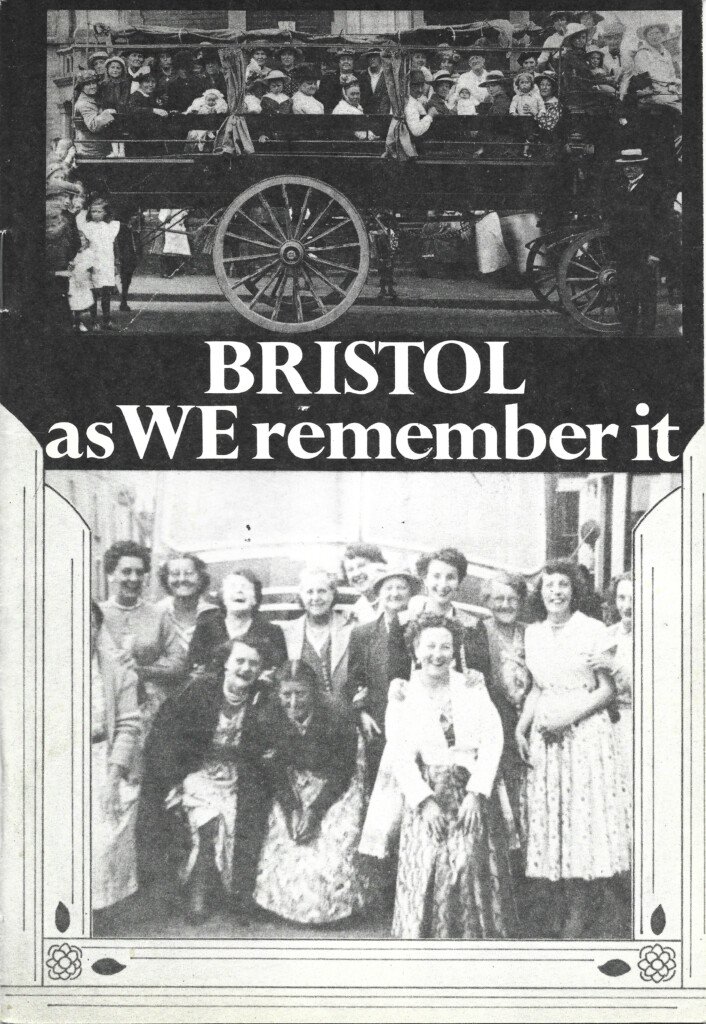

One of the first projects that Ian, David and Colin set up was the Writers’ and History Workshop at the Barton Hill University Settlement, which produced the booklet Bristol As WE Remember It. This involved interviewing ten people, many of whom had worked at the old cotton factory.

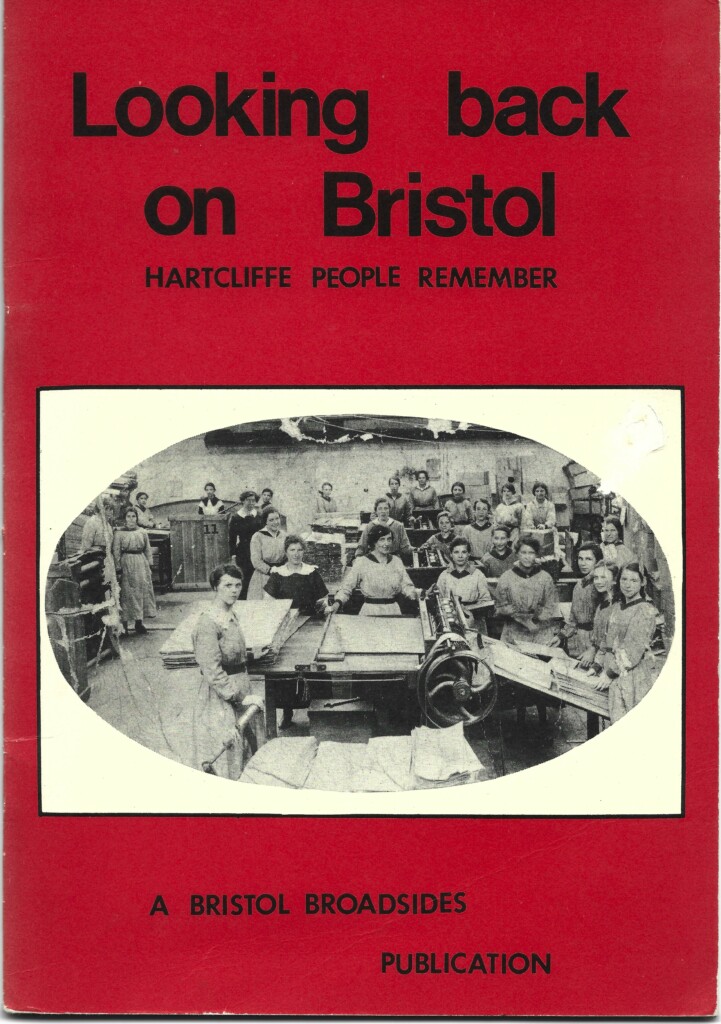

‘That wasn’t so much creative writing. That was history,’ says Ian. ‘And people would write but more often that was from tape recordings. Certainly that was the case with Bristol as WE Remember It. I think it was also the case with Looking Back on Bristol. We just recorded people’s experiences and published it. It was a very new look at Bristol history.’

The session opened with Ian and Colin introducing themselves and what they hoped to achieve, and then they recorded what the participants had to say. ‘It wasn’t like the traditional WEA lecture where you told people about whatever aspect of history you were talking about. We turned the tables on that,’ says Colin. ‘They told us what they wanted to talk about. And obviously we tried to steer it into particular areas: employment, education etc. And we recorded it all, transcribed it and tried to put it into some kind of shape.’

Bertel adds: ‘Ray Mighty from [trip hop band] Smith & Mighty, his mum was part of the Barton Hill group. I ended up having a chat with her and she was dead proud of being able to talk about working in the Barton Hill factory during the 1900s.’

1978

In the early days, Broadsides, which continued to operate out of Colin’s front room, was largely funded via Arts Council England, South West Arts, Avon County Council and Bristol City Council. That money went towards Ian’s salary and helping the organisation to function. ‘It was never easy,’ says Ian. ‘But we were able to raise enough funds to keep the organisation going until I left, certainly. I think people were quite open to the kind of ideas that we had, this notion of democratising writing and democratising history. It was very much part of a local and national movement. I reckon I spent about 25% of my time fundraising, which I felt was a bit of a waste of time. But it was part of the work because without that money we would never have survived.’

The booklets were sold ridiculously cheaply: as low as 30p initially. And they were printed in fairly high quantities of around 3,000, because the more you printed the lower the unit price became.

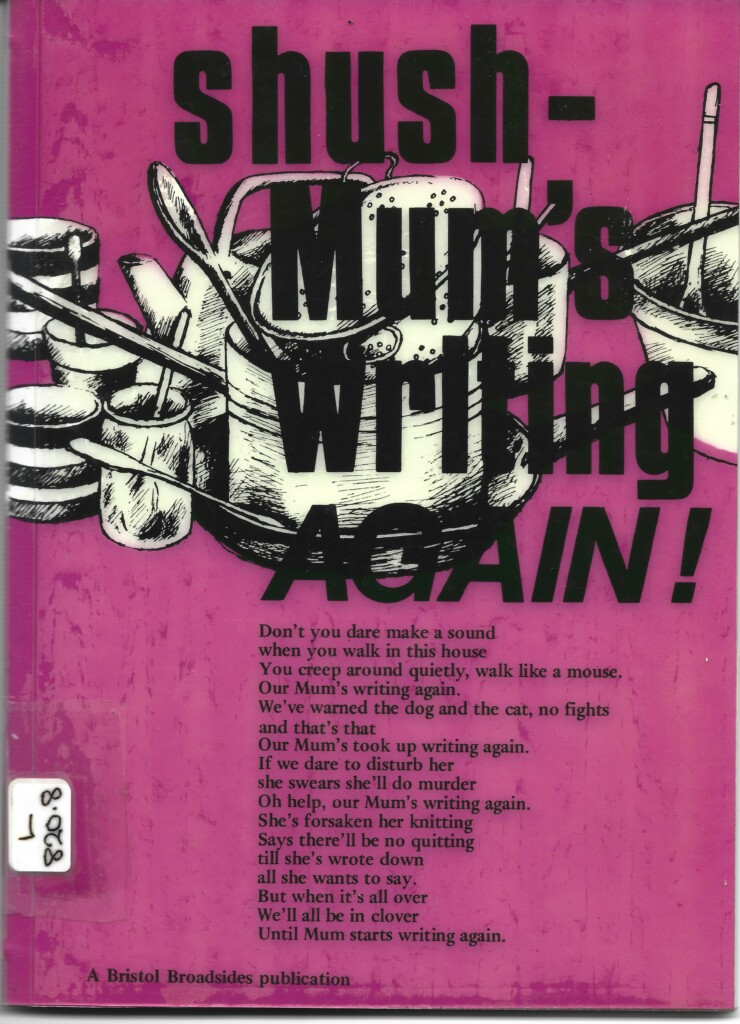

The women of Knowle West were busy, often juggling their writing with looking after their families and holding down jobs, just finding time to jot down some writing while waiting for the kettle to boil. Although the Knowle West writers’ group was co-ordinated by Bob Johnson from the WEA, it must have been a task trying to entice those women to come to a workshop in the first place.

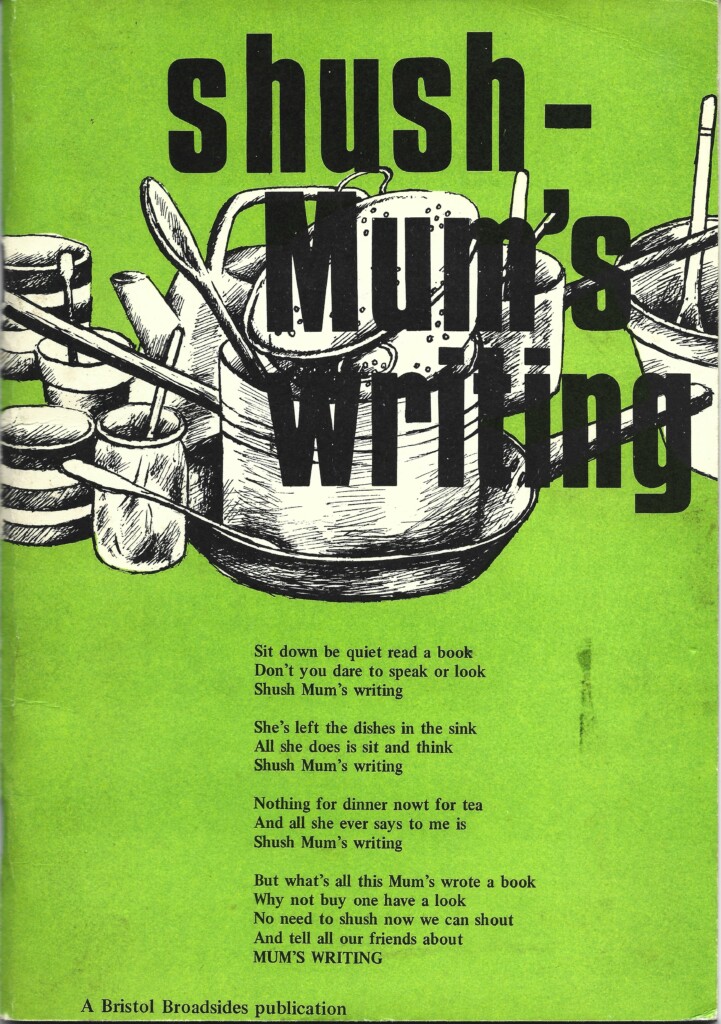

David says the answer was word of mouth: ‘You can put leaflets out until you’re blue in the face, but if you’ve got somebody who says, “I’m going to do this next week, why don’t you come along?” to a neighbour, that’s effective. It was “Shush, Mum’s Writing”, it wasn’t “Shush, Dad’s Writing”. It was their friendships. It takes an awful lot of confidence to walk into a room when you’re not used to those environments and be confident.’

Another difficulty with persuading working women to attend a writing workshop was understanding the priorities of those women, as David explains: ‘Shush, Mum’s Writing wouldn’t have happened if we hadn’t been there to encourage it. I remember Bob saying to me, “You’ve got to remember that if people have got primary needs, like the need to feed their family or need to keep a shelter over their head, [workshops] are secondary needs. They need to have all those things sorted first and then they can give emotional and mental space to doing something like this.”’

As David says, it was not easy for those women to escape to workshops: ‘A lot of those women were not in happy marriages. They weren’t supported by men. Some of them were single parents but not many of them. Often they were telling us that the men resisted what they were doing. The traditional family relationship is where the man is the breadwinner, the woman working for pin money. So a woman says, “I’m going out tonight to an adult education class. I’m thinking of applying to UWE to do a degree.” It broke up their marriage.’

In June 1978, to mark the publication of Looking Back on Bristol, Broadsides arranged for a 1940s bus to take residents who lived on the council estate at Hartcliffe back to Bedminster, Fishponds, St Pauls and Totterdown to see where they had grown up, and to revisit the locations of the stories they shared in that booklet. They were joined on-board by an accordion player for a singalong. Ian told the Bristol Evening Post on 17 June 1978: ‘We decided on the coach trip because we wanted to take the whole project back into the past. The coach adds authenticity to it’.

He says now: ‘Those areas changed and people’s lives changed because their old communities effectively broke down. You can read Jeremy Seabrook, who writes very eloquently about the way the old working-class communities broke down with people moving out to the estates where they were living at first very individual lives, and the communities took a long time to reconstruct themselves. Often they never did and it created huge problems. But in Knowle West, there were strong community feelings, and in Hartcliffe as well. The community centres there were very important because of all the activities that they facilitated, not least the writers’ and history workshops and everything else they did.’

1979

The Broadsides’ editorial board existed to facilitate the creativity of individual groups, not dictate ideas to them. By June, it had been decided that every member would pay a £1 annual subscription and receive a copy of the rules. Madge circulated her notes after looking into the finances of Broadsides, where she observed that the publisher was £100 in the black. She also highlighted there were problems in keeping track of where the stock actually was and that more than 1,000 booklets could not be accounted for.

As Broadsides gained momentum, it outgrew Colin’s front room back and, by June, Ian had moved the co-operative to an office on Richmond Road, Montpelier, which was shared with the Bristol Voice magazine. Describing the Bristol Voice, Colin says: ‘It gave a voice to issues that the Bristol Evening Post and Western Daily Press would not give a voice to, so it filled a void.’

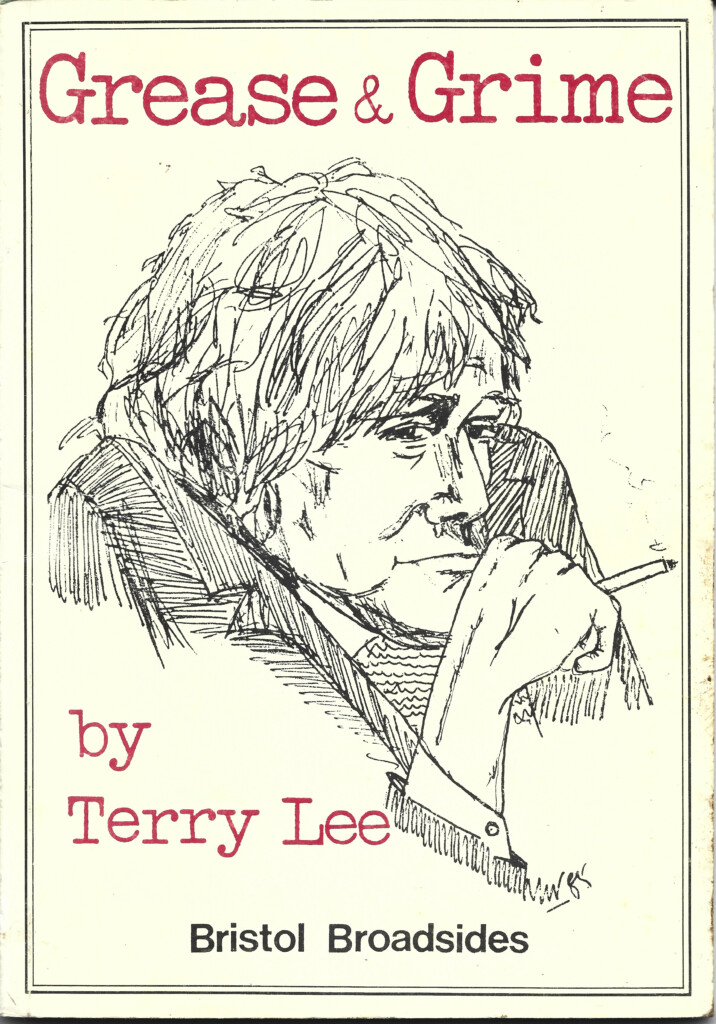

With both enterprises having strong political values, occasionally outside influences would impact them. Ian recalls the time that he and Bristol Voice worker Terry Lee were set upon by members of the National Front who objected to their work with the Anti-Nazi League: ‘We were working in the office … and we saw a couple of guys drive up the road and we recognised them as National Front. They drove up the road, drove back, got out the car and started to kick the door in and tear up the newspapers outside. We managed to stop them getting in … Eventually we did hear back [from the police] and the attackers were prosecuted. We went to court and they were convicted.’

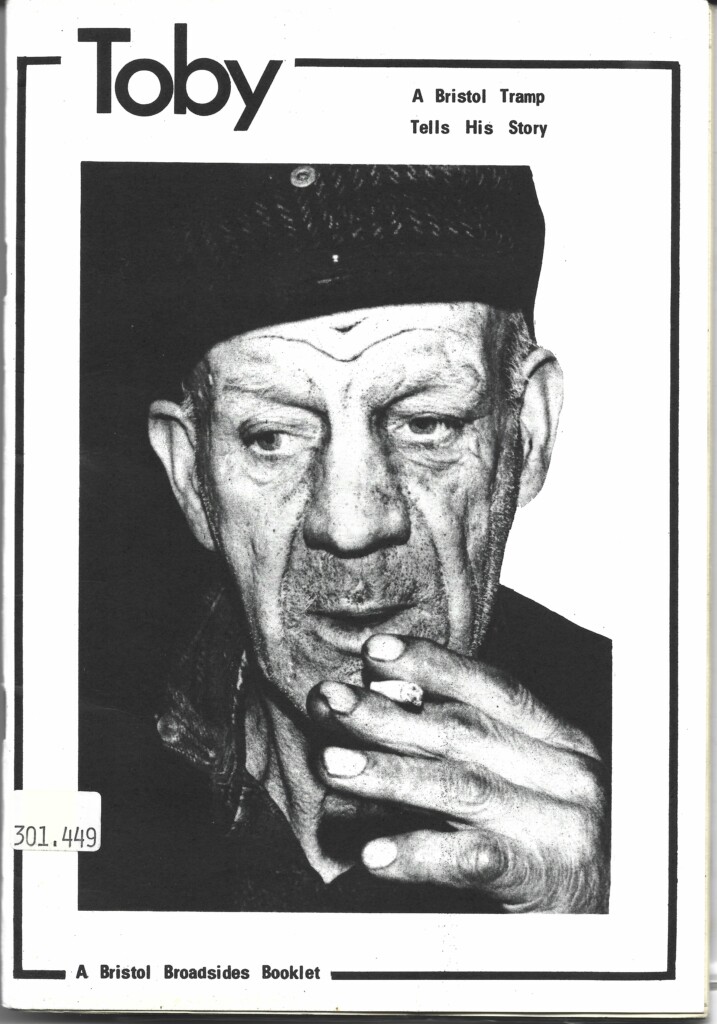

‘I’m racking my brain to think how on earth I got to know Toby,’ says Ian. ‘I think somebody just introduced him to us and said, “I know this guy, a tramp, a traveller who actually lives out in the woods in Ashton Court”. I interviewed him. He was a poet, philosopher, tramp. It was an incredible story of his life.’

1980

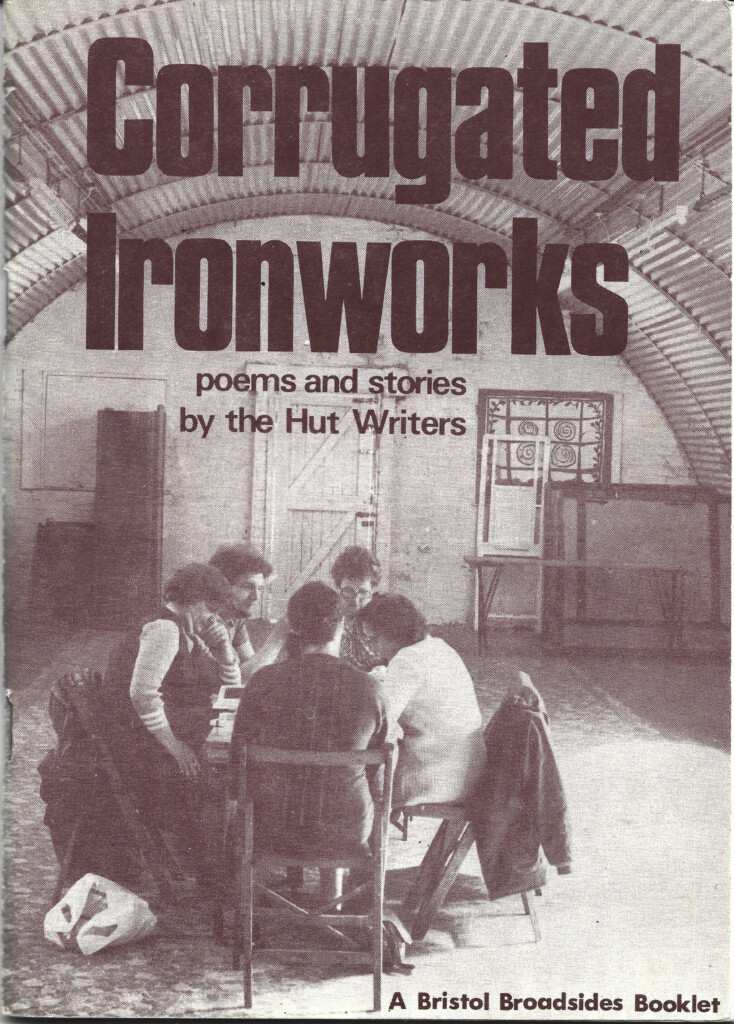

Broadsides was becoming much more established by 1980 but money would always be a problem. The minutes from a meeting in October debate the cost of printing 3,000 copies of the Corrugated Ironworks booklet, while also stating that Bristol Council had not extended its grant meaning that Ian’s salary was at risk.

Two booklets came out this year, and there was an exhibition at the Bristol Arts Centre of female factory workers that was accompanied by Broadsides’ booklets. The exhibition included work by Hazel Gower, who would illustrate both of the Shush, Mum’s Writing books.

1981

By 1981, the finances were a little more secure. With £5,000 from Arts Council England, Ian’s salary was safe for the next year and sales remained steady. Things were also looking up for the Federation, who had some funding for writers to attend a trip to America. Maureen Natt from the Southmead group was interested in going on behalf of Broadsides.

With three writers’ workshops now established, an application was made to the Arts Council to set up two in Easton and Bedminster. While the new chair Kathleen Horseman made it clear that she would like better communication between all of the Broadsides writers’ groups.

All of this buoyed Ian into thinking it was time to expand Broadsides and he presented his plans in March. A key part of this document is the instability Broadsides faced by being so reliant on external funders and the need to try and become self-sufficient. ‘I don’t want to see Broadsides stagnate or collapse,’ Ian wrote. ‘I would like to see it grow and develop along with the worker writer movement.’

1982

Bristol Writes: Writing By Local People No 1 and No 2, 1982: A magazine format providing a forum for writers who are not professionals. Most of the writers in this collection come from the workshops in Bedminster, Easton and Southmead.

A new group was begun this year at the Albany Centre in Montpelier, which Ted Fowler attended: ‘I really wanted to be able to write. That was my way of trying to make sense of my world.’

It was around this time that the Full Marx radical bookshop was being set up on Cheltenham Road, with which Bristol Voice and Bristol Broadsides inevitably had a lot of crossover. Ian was one of those involved in helping to set up Full Marx, along with the academics Ellen and John Malos, plus solicitor Kate Kay and her husband Norman (who had attended Hackney Downs School with Ian) and Liz Jones. In time, Broadsides would move into the office above the bookshop.

Ted, who worked at Full Marx, says: ‘There were various brands of Irish nationalism who hated each other and were being constantly watched by the police. Every now and then there were problems about that. But then that was the reality of the time. The anger between the left-wing groups was also sometimes focussed in Full Marx, and that made it quite unpleasant for ordinary people to come and browse. But I would try and shoo them out the shop because we needed to sell books. We weren’t going to change the world by having an argument.’

Bertel was a member of the Easton Writers’ Group and adds: ‘That area was quite run down. It was very Bristol with grassroots initiatives happening. At that time, Broadsides were in 108c Cheltenham Road. And then you had Full Marx, and Demolition Diner would have been going through some of that period. It was a time when there was a lot of social changes happening. Hitting with the punk era, there would have been the union changes happening. And for that area, it was at the time when it was very clear we had, like myself, first generation Black British. When the Black community got there, it was starting to be a residential area. It was quite a dynamic period of time.’

1983

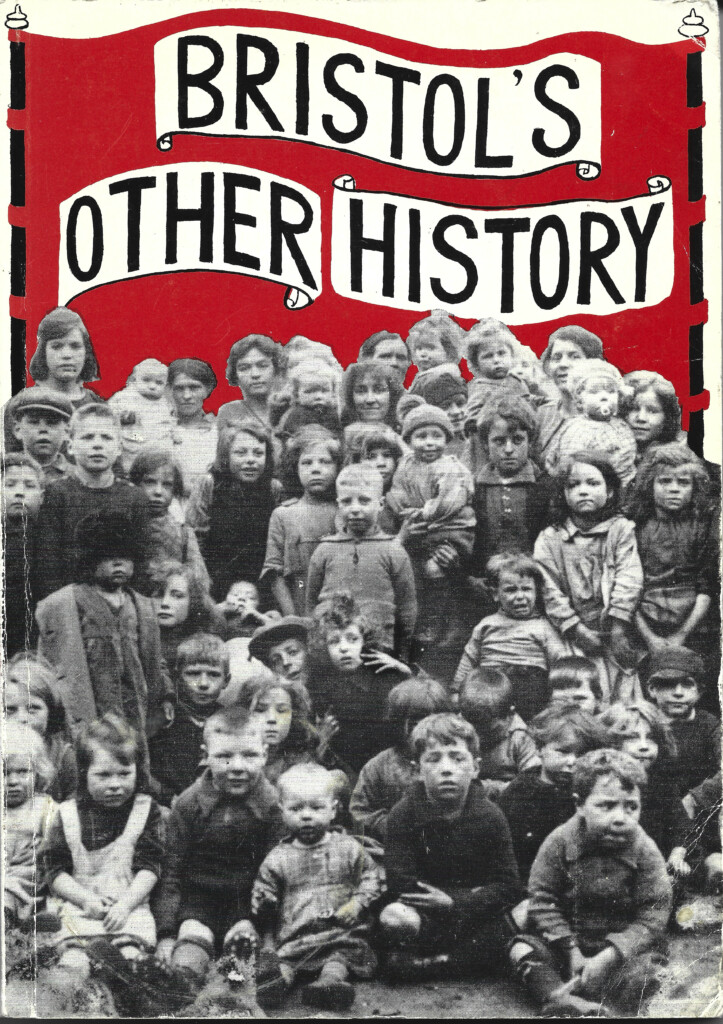

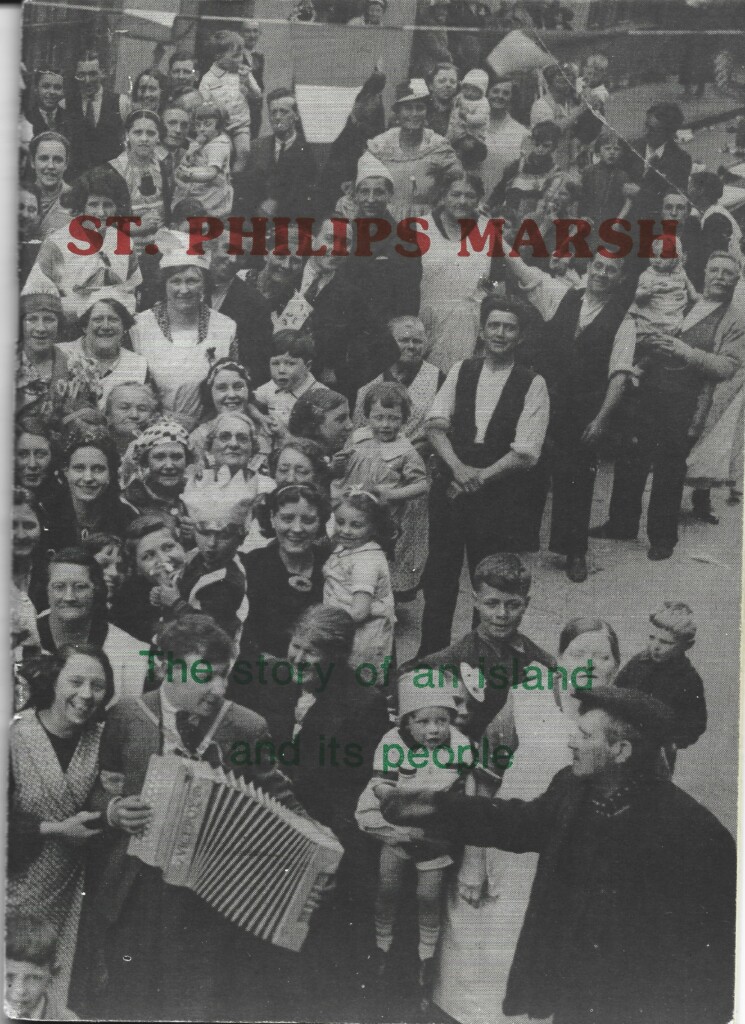

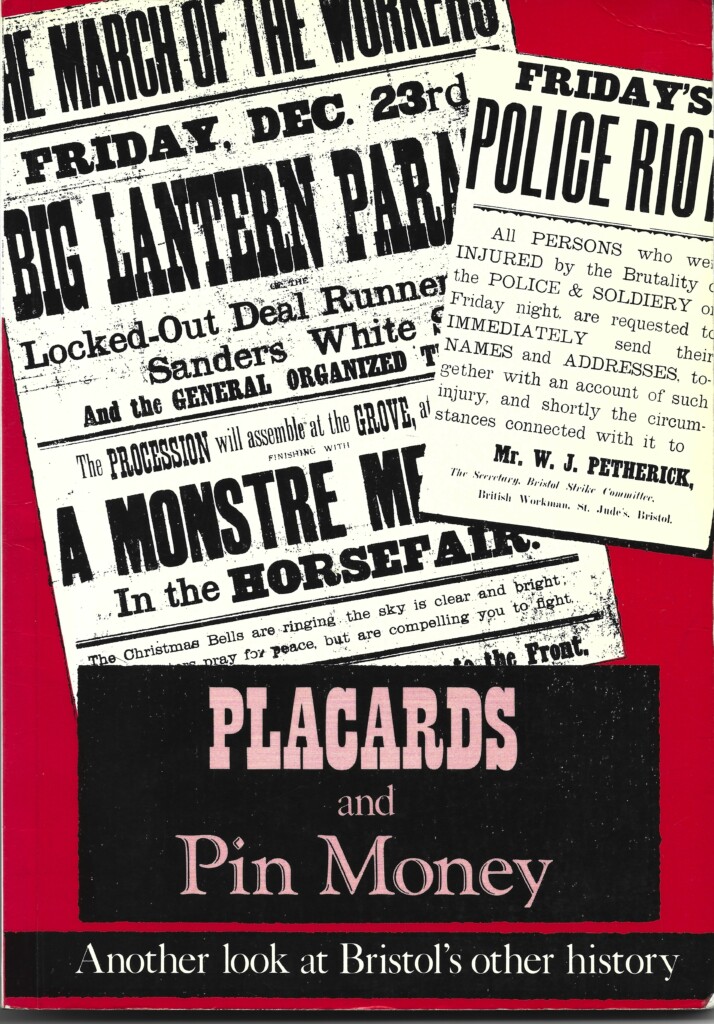

Broadsides introduced a series focusing on radical local history with a series of books written by academic or professional people. The first of these was Bristol’s Other History.

‘That goes back to what I was saying about my work in Hackney, because there already were two strands, community publishing and the workers’ history movement,’ explains Ian. ‘There was the Hackney People’s Publishing Project, and then there was Raphael Samuel who was doing academic research into history from the point of view of working-class people. As academics, they put the stuff together and made a thesis out of it. The two strands for me were always equally important. There was never a question of offsetting one against the other. It’s important to listen to people’s experiences, but it’s also important to listen to historians who are evaluating and studying working-class life.’

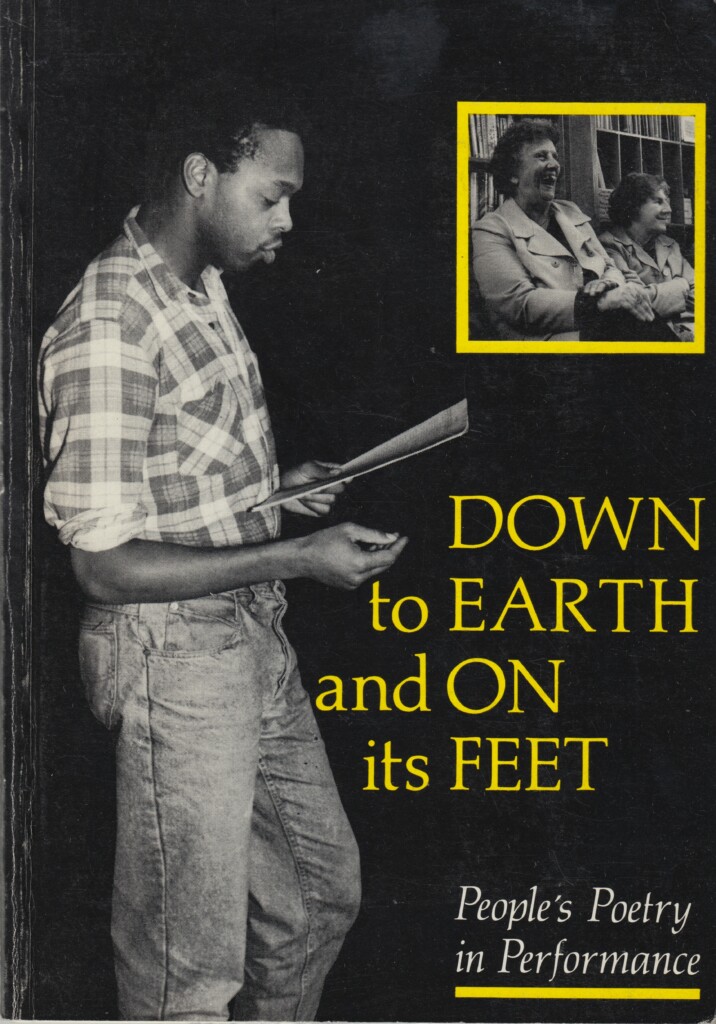

There were also some live performances where writers and poets read out their work. But not everybody felt comfortable with public speaking, so chair Kathleen suggested holding a workshop to help with performance skills. This turned out to be very popular and would be repeated several times over the following years.

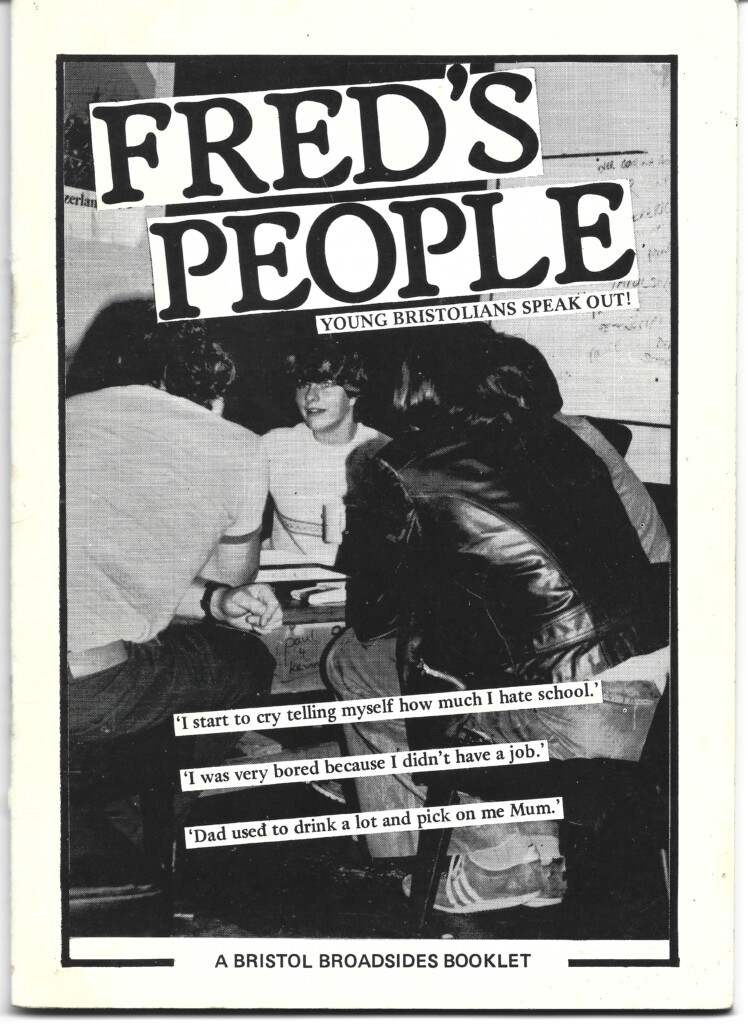

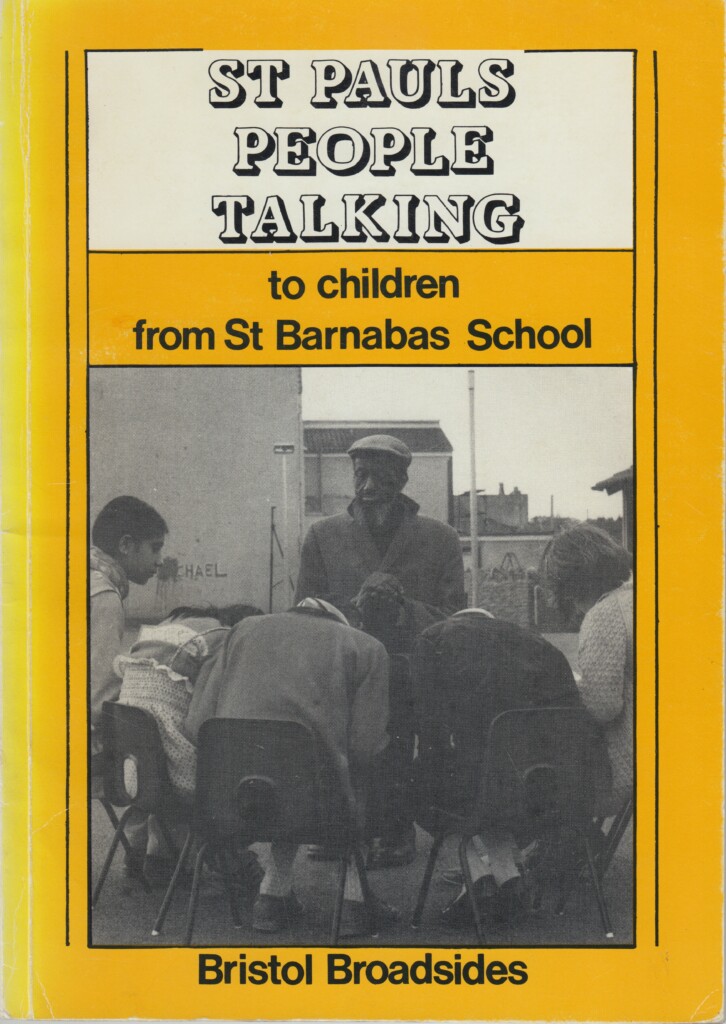

The final book of the year was St Paul’s People Talking. Ian explains how this book came about: ‘Organisations would come to us and say, “Hey, we’re doing this project. Would you be interested in being involved with it and perhaps publishing the results?” We were approached by Community Service Volunteers. They were doing work in schools and getting kids to talk about their lives. I remember involving the children and the teachers in the publishing process. I took them along to the printers to show them how books are made. I thought “That was good. It was a good thing that we did then.”’

1984

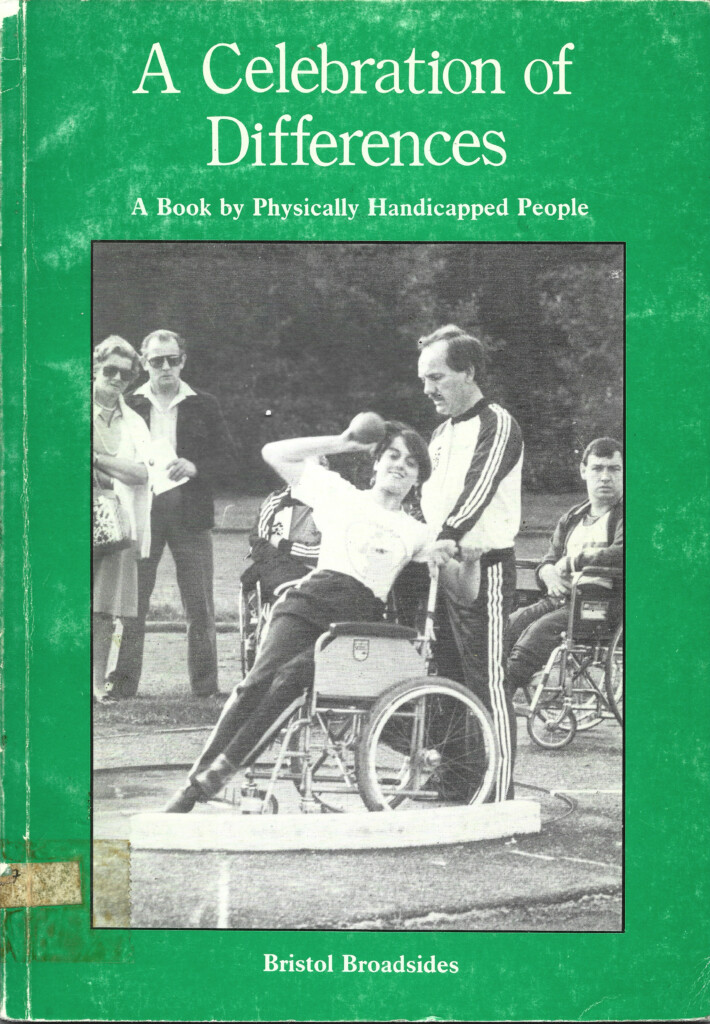

Ted says: ‘One of the things that Broadsides helped to do was to put in print, often for the first time for most people, and in an inaccessible and easily findable way, stuff that wasn’t being talked about, and disability rights or the voices of disabled people was definitely one for me.’

Things were running smoothly by 1984: a number of books were planned for the year ahead, it was decided to scrap the annual £1 membership fee, and 12 Broadsides members attended the Federation AGM with the outcome that Jean, one of the members, would attend a Federation trip to Ireland.

The meetings and trips organised by the Federation are widely agreed upon as a highlight. There was one big conference a year, which took place over a weekend, offering workshops, performances and meet-ups. ‘I lived for them,’ says Laura Corballis, who would later become Broadsides’ co-ordinator. ‘Meeting people who were really into the whole project and not into having a fight about it, and loving the sharing of writing and listening to people perform their writing. I met some great people that way. One year I drove my little Lada up with [Broadsides’ writer] Joyce Storey and her daughters, who were all hysterically funny. How we didn’t crash I don’t know, because they spent the whole ride telling ridiculous stories and I was driving through tears of laughter.’ Ian adds: ‘I got to see parts of the country I’d never seen before. And my two boys, I would always take them and they made friends with people all over the country. It was a national movement but it wasn’t that each group was doing the same things. But they all came together in the Federation.’

Ernie Ross was a member of the Easton Writers’ Workshop who approached Broadsides with a book he had written about his experiences of working on the railway. When the rest of the committee had read the book, it was quickly agreed that they should publish it and Tales from the Rails has since become one of the publishers’ best remembered books.

Financially, applications were being (unsuccessfully) submitted to fund another worker to help Ian with his workload. In addition to his work in the office, Ian was overseeing three of the weekly writers’ workshops. This drew to a head the issue of how Ian should best be spending his time: on attending workshops or on assisting with publications. By August, there were six writers’ groups (Bedminster, Easton, Patchway, Southmead, St Pauls and the Unemployed Writers, although the latter would close by the end of the year), meaning that Ian’s time was stretched very thin and the demand for Broadsides’ publications was growing.

By the end of 1984, Broadsides was also having to look for a new office as the property on Cheltenham Road was threatened with demolition. Alongside this, the anthology Burning Words was launched with an outdoor event at Broadmead shopping centre with some of the contributors performing their work to the public.

1985

The co-operative was certainly on a roll by now and everyone was kept busy. In addition to all his other jobs, Ian was presenting at workshops around the UK advising other people on how to set up a publishing enterprise. However, he also expressed a wish to move to part-time work eventually.

Bristol City Council offered Broadsides a grant of £15,000 for capital equipment. However, there was bad news from the Federation who, Ian reported, were ‘broke’, having had their Arts Council England money stopped. This meant the AGM could no longer be subsidised and members would have to pay £35 each to attend, although Broadsides had always subsidised attendance for its members. In a similar vein, it was (again) felt that because funding applications were so time-consuming that it was time for Broadsides to go self-sufficient. This meant sales needed to improve and, to help with this, Ian proposed a series of working-class novels and autobiographies, which was agreed by the board providing that South West Arts would match any funding Broadsides raised.

There were plans to send a group of writers to perform some of their work in support of the striking miners, although this was called off at the last minute. ‘I think the miners’ strike was both a bringing together of people and a demoralising of people,’ says Ted. ‘There was also, in those days, quite a focus on local government being able to do things, but local government started losing its power from about 1983 with something called rate capping, where the government had determined that you couldn’t raise a tax more than a certain amount. So there was less freedom to act from local authorities, to do interesting things, whether they be small, like funding Broadsides, or big, like building new schools.’

Performances in public spaces continued, with Terry Lee helping to make several of these happen, including one in Broadmead shopping centre on a Saturday morning in July. By the end of the year, Terry would become chair of Broadsides.

The filmmaker Lee Cox created a photograph exhibition of some of the writers’ groups to further promote Broadsides, but arguably they didn’t need many new members at that point owing to an effective call-out on local TV, which saw attendance at the workshops more than double. One person who saw that HTV promotion was Bertel Martin: ‘Just before the news, they used to do these community announcements. In fact, it was Kath Horseman who was on and she said, “If you’re interested in writing, come along to Bristol Broadsides.” The meeting was at the old Co-op on Chelsea Road, and I just turned up and Ian was coordinating. That was around 1983. I had never been to any kind of workshop before. It was totally informal. Everyone had little notebooks and little folders with poems in, and I just had this tatty bit of paper in my back pocket and took it out and read. And they were really encouraging so I continued meeting.’

With the rise in members and the increase in popularity for Broadsides’ history books, it was decided to encourage individual groups to self-publish their anthologies as these generally didn’t sell so well. As such, the Easton group independently put out an anthology called All Our Own Work. By the end of the year, there were seven writers’ groups, as well as requests for new groups in Stockwood and Barton Hill. Broadsides was bustling.

Kathleen Horseman and Lorraine Blake had work published in an English textbook that was being used in schools. Kathleen also put in a request for a book that focused on the work of women writers, and this idea was passed by the board. It would be published in 1986.

Broadsides had never paid royalties to any of its writers: there just weren’t the funds to enable this. But in June, Ian drafted a document for the board to consider the idea of paying nominal royalties. After much discussion, it was agreed to pay royalties of 5% of the cover price to individual authors, but not to contributors to anthologies. This would take effect from January 1986.

1986

The ongoing problem of funding Broadsides rumbled on. However, South West Arts promised a grant of £5,200 towards the series of working-class novels and autobiographies, on the proviso that this sum was matched by the local authorities.

Alongside the writers’ workshops, Broadsides was leading on performance workshops to help people build their public speaking skills, and these were largely organised by Tony Lewis-Jones. Broadsides was also asked to present a workshop at the Avon English Teacher’s Conference to show English teachers how they could use Broadsides’ work in schools.

Back in the office, Ian handed in his notice in March after more than eight years with Broadsides. His notice was accepted ‘reluctantly’ and he agreed to stay on until his replacement was found, at which point he would oversee the working-class novels and autobiographies series. In June, Norma Jaggon and Phil Smith started on a job-share basis. They were both put through their paces straight away and, despite being paid for 17.5 hour weeks, they were effectively working full-time.

The Women’s Writers’ Group set up a Creative Journal Weekend for Women, and accepted £200 from Broadsides to help make this happen, promising that the money would be recouped via ticket sales and returned. The two-day workshop was led by Simona Parker and explored dream life and personal issues.

Following Kathleen’s proposal for a book by women writers, the Women’s Writers’ Group published an anthology under the imprint of Word Women. The Women’s Group were also leading on the Avon Poetry Festival, which culminated in an event on 8 November at the Albany Centre and saw a series of poems by Broadsides members being published every day for a month in the Bristol Evening Post.

Placards and Pin Money was almost ready for publication by the time Norma and Phil joined Broadsides, which meant that one of their first tasks was the unenviable one of manually preparing the text to print. ‘It involved putting up bits of text that had come back from the printers and pasting them up onto these boards, which was very fernickety,’ says Phil. ‘The text was sent to the typesetter, it would come back to us on these sheets of paper, which we’d then have to cut up and paste onto boards, which then went to the printer. That was very stressful because if you cut it off wrong, you’d have to paste little tiny bits back in.’

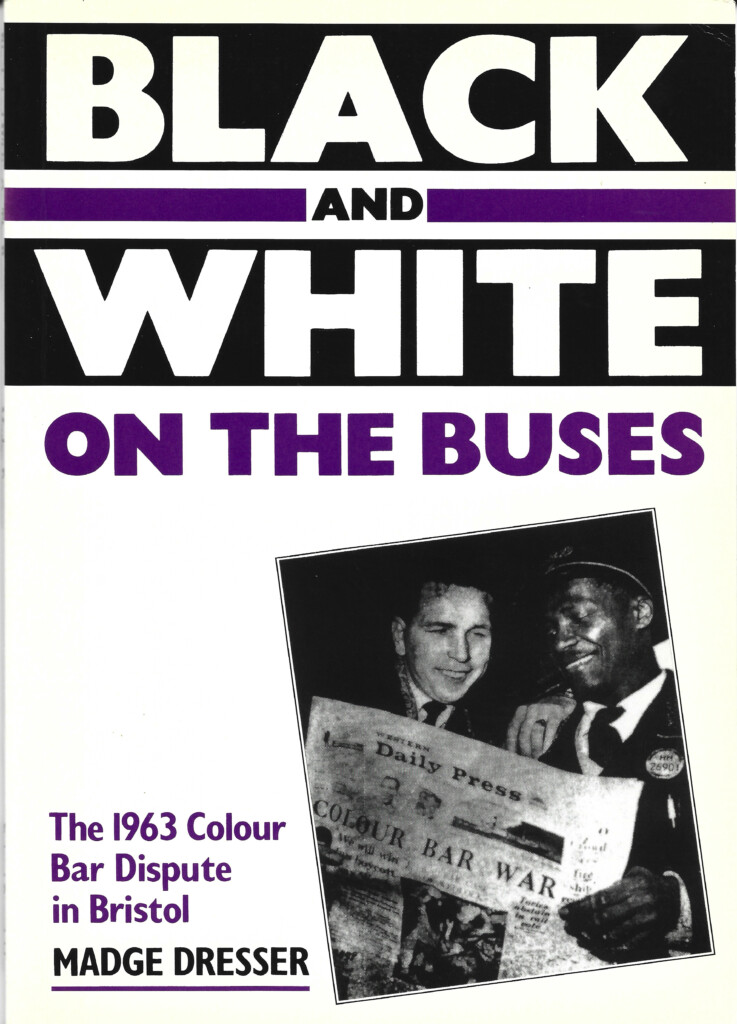

Bristol-based civil rights campaigner Paul Stephenson, who had been central to the Bristol bus boycott, had read Madge’s essay in Placards and Pin Money and felt it to be so important that it was worthy of being a standalone booklet: this idea was agreed on.

‘It was something that we probably should have done more of,’ says Ian. ‘I think people were shocked in lots of ways, simply about what had happened not that long ago on the buses and the level of racism and discrimination that had taken place in Bristol. I think it uncovered a whole area of hidden history in Bristol.’

Madge explains: ‘I was aware that there was a PhD student, the first Black PhD student in criminology, who did the controversial book Endless Pressure. His name was Ken Pryce, and he wrote his material before me but what I hadn’t quite realised was that by digging into his actual PhD dissertation he had outlined the story about the Bristol bus boycott. Since then, people have said that I was plagiarising his material but his was from a slightly different angle and, in good conscience, I hadn’t realised the connection. In any case, I was quite interested in getting some insight into some of the white actors who were involved in the story and also talked to some of the Black activists who were behind the boycott. I did feel that if there hadn’t been interviews with people like Paul Stephenson and Owen Henry and Roy Hackett that they could have been forgotten in the long term.

Madge added: ‘My pamphlet Black and White on the Buses got a lot more attention at that time than Ken Pryce’s footnotes in his PhD dissertation. Looking back, my research techniques were very sloppy and were subsequently criticised, but at least I had made an effort to rescue these stories from oblivion. However, the book was accessible enough for people who read it to feel quite inspired. I felt my instincts with Black and White on the Buses had some merit in the sense that it kept the story alive and queried some of the more orthodox interpretations of trade union opposition to employment of Black people, which was based on fear of workers being undercut by cheap labour. Coming from America, I knew that there was a lot of opposition to the employment of Black people that had a sexual route, fears of miscegenation, rape etc, which didn’t seem to be in the discourse about racism in the Labour party at that time.’

Horfield Prison had also put in a request for someone to lead a writing workshop for inmates. Phil was chosen to be the co-ordinator: ‘I just ran it as I ran the other workshops, which was to invite the participants to share the writing they were doing. And then the rest of the group would share their responses to it. And it was an opportunity for people to tell their stories. Sometimes they wanted to tell the story of how they ended up there, or why they shouldn’t be there, or what they were experiencing in the jail. And sometimes they were telling other stories. Sometimes they wanted to talk about more fantastical, fictionalisation things, and sometimes they wanted to remember things.’ He adds: ‘I can remember how relieved I was when [each session] was over… hearing that door shut behind you. I can’t say that I was working with happy people.’

Being in a prison, the attendance in the group fluctuated, as Phil explains: ‘Sometimes it was very irritating, just as somebody’s writing was blossoming, they’d be transferred. Hopefully they’d get out but I think most of the time people are on remand. I think most of the time we had six, seven, eight people. One or two of the prisoners I felt really should be having psychiatric care. They might need to be locked up but not in a jail. They were not being looked after. They were definitely borderline schizophrenic, hallucinatory, delusional, whatever. And they were often rather good poets because they had access to a strange fictional universe. There was a lot of intensity flying around the room. People aren’t writing inconsequentially. If they’ve bothered to come and they’re writing, they’re writing about something that’s important to them. And irrespective of the facility with which they’re writing, it’s stuff that demands respect and attention.’

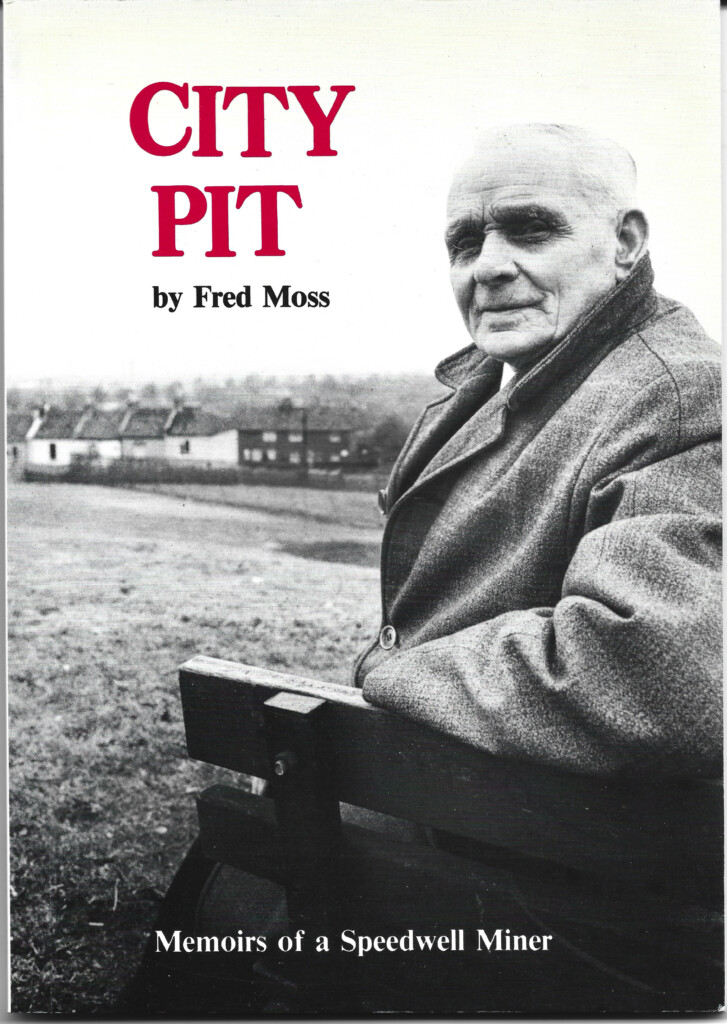

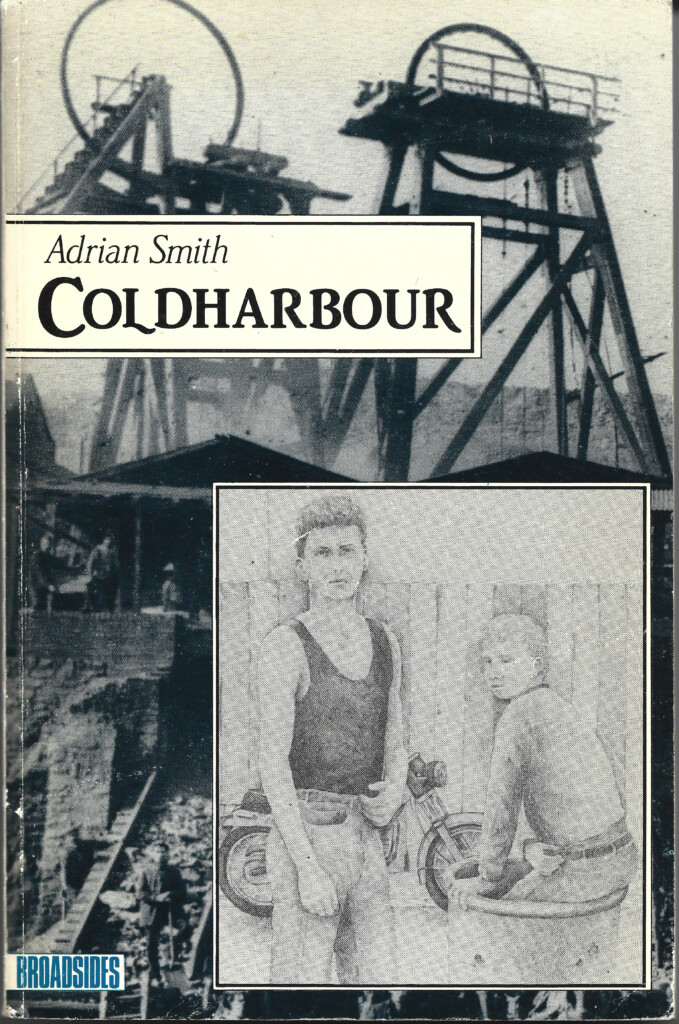

New member Myna Trustram, who was an academic researching the East Bristol coal mines, had come across a former miner called Fred Moss who had been writing his memoirs and she presented this to the board for consideration. Bertel recalls: ‘City Pit was one which really hit well for me because it was something I never really considered. The mines I’d heard about were the Bedminster side. I hadn’t thought about the Speedwell side. And I think it was also the fact that in the book they talk about the Davy lamps, and someone then telling me that, “Oh, actually, Davy was from Bristol.” And them saying about the explosions which used to happen, and suddenly something which is quite key to history, you’ve got this person writing about it and they were a small part of it as a young lad.’

Having decided to pay royalties of 5% as of January, by September some members felt that should be increased to 10% given that most of the writers were unemployed. Norma tried to explain that the print runs were too small for Broadsides to be able to afford this and that the profit on each book was already minimal. Norma then raised the issue of whether Broadsides could even afford to continue paying any royalties at all.

1987

In March, Ian left Broadsides and moved to Germany where his partner Uta was from. But of course, this created some big shoes for someone to fill, as he says: ‘The problem is when you have somebody who’s at the centre of an organisation and who effectively set it up and holds all that information, you have to let go. I probably let go too late. I think the organisation ran into certain problems after I left. I don’t know that the structure was strong enough … Because I was doing it 24/7 effectively, I held all the information. In retrospect, I think that can be a problem with an organisation where you’ve got somebody who’s central and the structures perhaps weren’t developing properly for a time when I was going to leave.’

Writing in support of Ian, long-standing member Pam Davis, part of the Bedminster group, told the Bristol Evening Post on 28 February 1987: ‘Without [Ian’s] quiet strength and guidance, Bristol Broadsides would not have survived, less still grown as they have … Ian often had to use all his skill and strength to keep Broadsides going, while people like me attended groups unaware of his worries and problems.’

Back in the office, joint co-ordinators Norma and Phil were taking courses in marketing and publicity, South West Arts confirmed funding of £11,750, and the Avon Association of Teachers of English were now basing some English GCSE courses on some of Broadsides’ books, while Grease and Grime and Burning Words were being used in schools by the Resources for Learning and Development Unit.

1987 also marked the ten-year anniversary of Broadsides and this was celebrated with an all-day event at the Folk House on 20 June, featuring workshops, poetry, playwriting, women’s writing, short stories, readings and more. The event saw a disappointingly low turn-out, although it was enjoyed by those who were able to come.

In September, Bertel was elected as chair… which came as a surprise to him. He recalls: ‘They said, “There’s an AGM, do you want to come along?” I didn’t even know really what an AGM was. I think I got a phone call from Tony Lewis-Jones saying he wanted to congratulate me on being the new chair of Bristol Broadsides. I didn’t even know what it was! But I bit by bit picked things up.’

Meanwhile, member Peter Mitchell was appointed as sales rep to try and get the books into even more shops and to keep on top of stock levels. ‘He was really good,’ says Phil. ‘He was going around all these little newsagents, but also the big WH Smiths and whatever, and getting orders for these books. He really took it on and did it really well.’

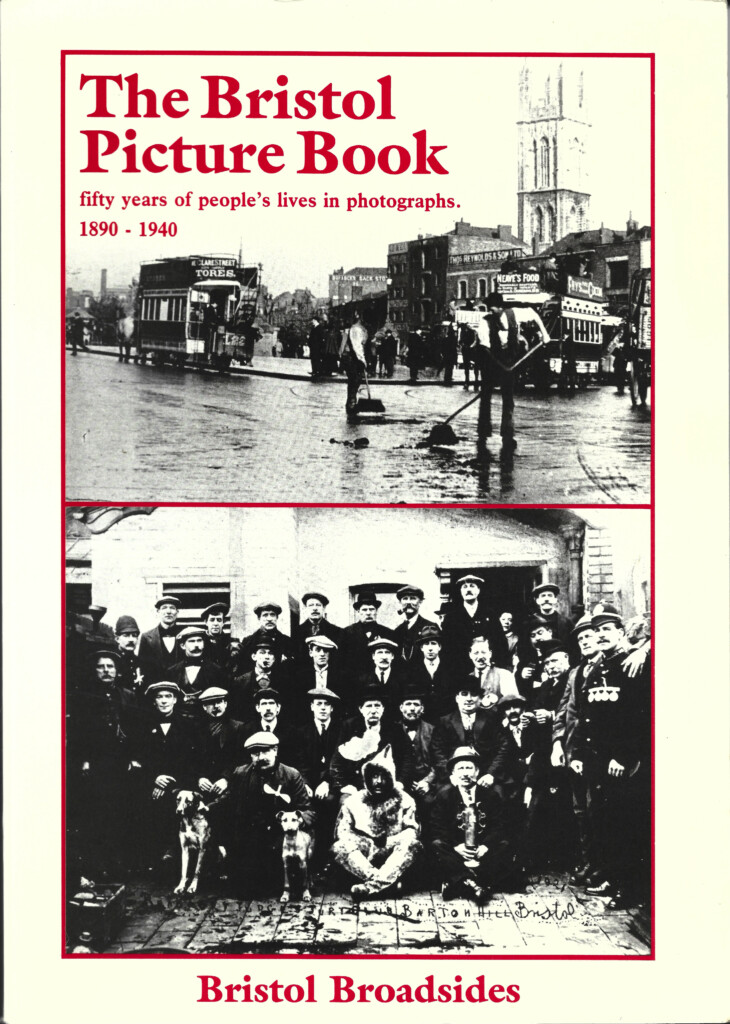

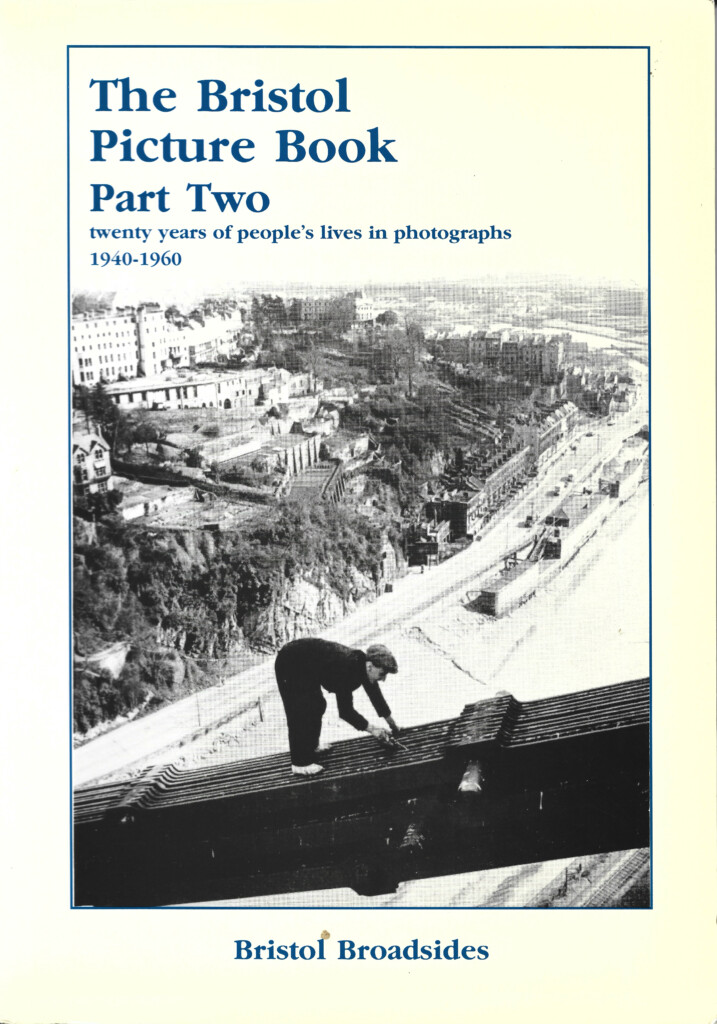

However, the seeds of discontent were starting to grow within the co-operative and it seemed to stem from the second ‘Bristol Picture Book’, for which one member was paid £200 to do some vital research while other members felt that the paid work should have been better advertised so that others could have had the opportunity to apply for it. They also said that other people had helped on the book without pay. This matter caused a lot of upset that rumbled on in meetings for quite some time.

Things escalated and, in November, a special meeting was called at the Folk House. Members were told that South West Arts were holding a review into Broadsides’ work and finances so that they could consider how best, if at all, to support Broadsides in the future. At the same time, both Norma and Phil handed in their notice.

‘It was a fairly stressful job coordinating Bristol Broadsides in some respects,’ says Phil, reflecting on why he and Norma left simultaneously. ‘I might partly have been just running away from it. It was enormously rewarding in many, many ways, but it was also quite a lot of stress. There was a lot of diplomacy involved. There was quite a bit of financial stress, in the sense that we were gambling quite a lot of the time with money that we didn’t really have. I think we produced 13 publications in the two years that Norma and I were working there, which partly might explain why we went!’

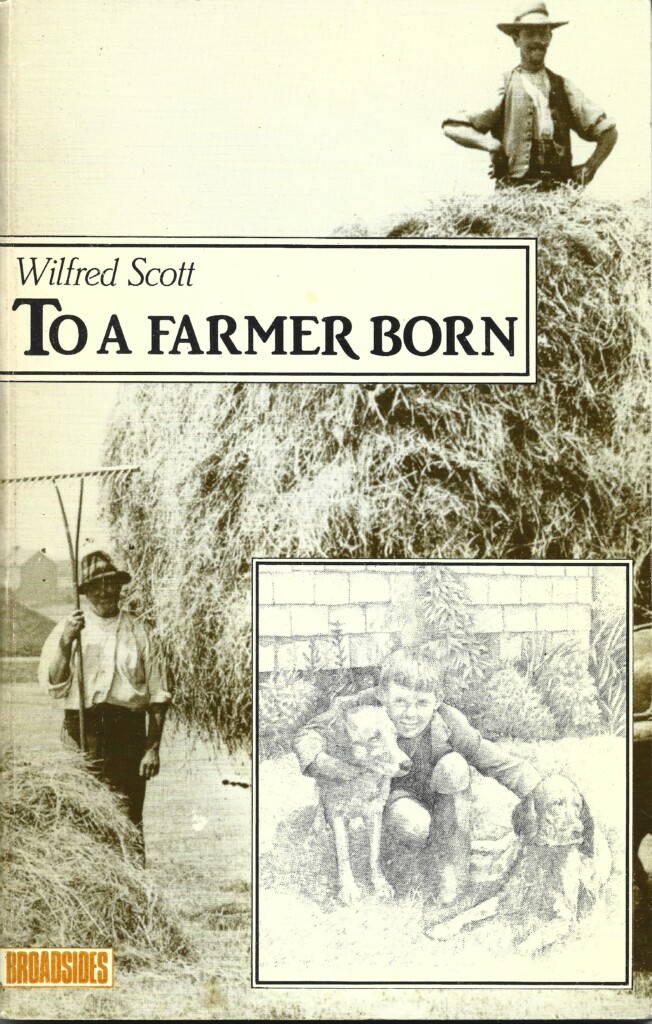

Meanwhile, the working-class novels and autobiographies series that Ian had established had come to a head and the first three books in the series of four were published. Thinking about why the series didn’t take off, Phil says: ‘We were struggling to get the quality and to have it from a working-class perspective. We were getting some pieces but they didn’t really connect with that ethos at all. And they didn’t sell.’

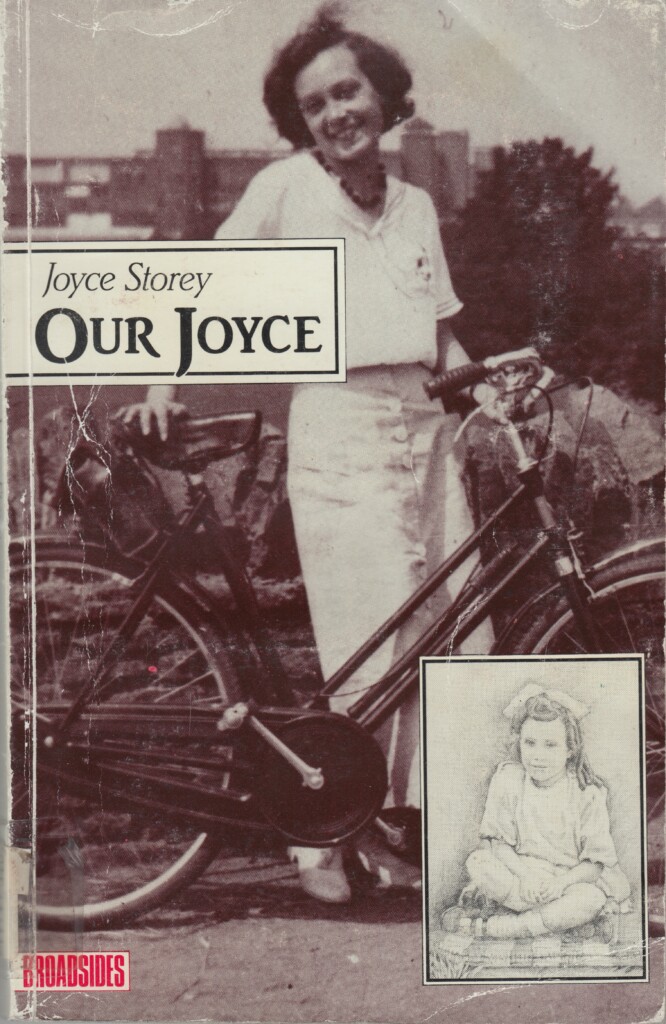

Bertel says: ‘[Our Joyce] was great. It was a really good success but we kept it still within the ethos, because what Broadsides did was have an editorial board. It was a group of people who are reading the books and selecting which ones were worthy of publishing, but also sticking with the ethos of making sure we gave strong feedback to the people who weren’t successful in getting published. [Broadsides] was ahead of its time. I think everything ends up being remembered for how it collapsed rather than its successes, but it had some amazing successes and it’s developed people incredibly.”

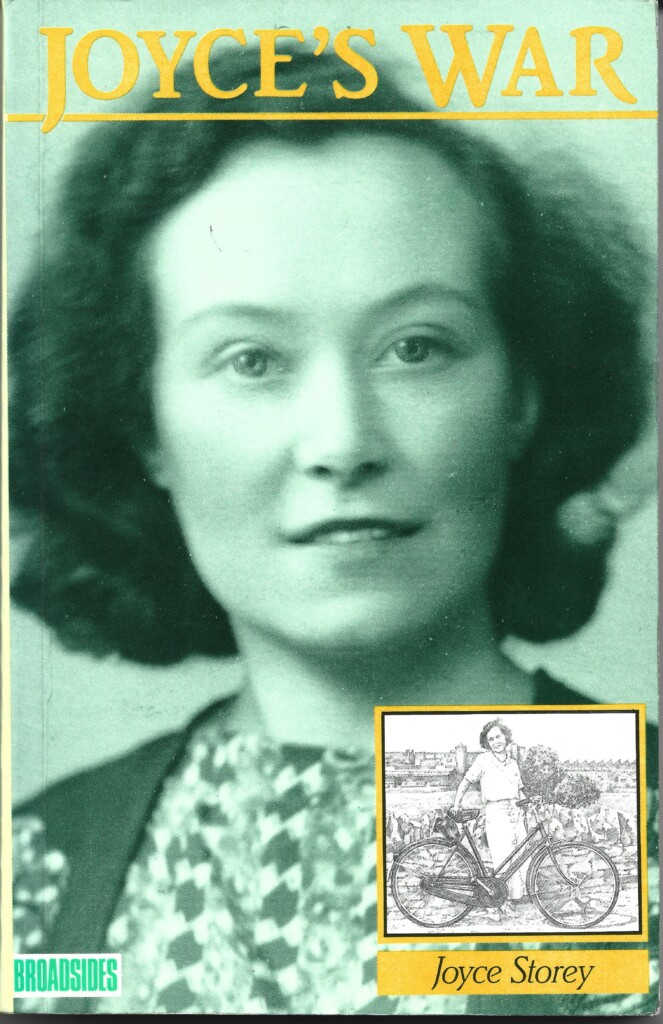

Joyce Storey from Lockleaze enjoyed the most mainstream success of any author associated with Broadsides. Among the accomplishments she saw was that her working-class memoir inspired some English teachers to task their students with writing the biography of somebody that they knew as part of their GCSE coursework. Joyce told the Bristol Evening Post on 4 July 1991: ‘It never occurred to me when I was young that I could write. This is a marvellous way for the children’s creative abilities to brought out. They’ve done some smashing work’. Teacher Helen Salmon added: ‘Joyce really fired them up and it all took off from there. It has been far more than just a piece of English coursework. They weren’t learning about events as historical facts that they might find in a textbook, but as realities in people’s lives.’

Yet Joyce wrote all three volumes of her memoirs with rapidly failing eyesight, as she explained in the Bristol Evening Post on 27 October 1987: ‘I was typing without being able to see what I was doing. [My daughter] Patty was on my wavelength, she understood what I was trying to say and retyped the pages so they were readable.’ With humility, she told the same paper on 3 April 1990: ‘I still don’t understand why people made so much fuss over Our Joyce. I only went to an elementary school and all I do is put my thoughts on paper.’

In September 1991, Joyce won the Raymond Williams Community Publishing Prize for Joyce’s War, which saw her receive a cheque for £2,000 to be shared with Broadsides. In 1992, all three volumes of Joyce’s memoirs were reprinted in by the mainstream publisher Virago, who later bundled them together in book in 2004. ‘Me being a writer was the shock of the century. My mother would never have believed it. “What, our Joyce?!” she’d have said,’ Joyce told the Western Daily Press on 11 September 1992.

It was a humble poetry anthology that caused the most disharmony among members. Phil recalls how one of Broadsides’ funders donated £500 and the group decided to put out a poetry anthology, which initially went very smoothly in terms of selecting the work to print. But it was at the printers that everything went wrong… when the printers said they could print extra copies for the same money if they used recycled paper. Needing to make a quick decision and having no time to consult the membership, Norma and Phil agreed.

‘You have no idea of the stick we took for that! Dear, oh dear!’ laughs Phil. ‘People thought it looked like lavatory paper. People just looked at it and were so disappointed. So even on a relatively trivial thing, we could see it could blow up. To look forward to [seeing your work in print] and then to feel like you’ve had your work published on lavatory paper, it was really disappointing for people.’

In the minutes for a meeting around this time, it was noted: ‘Tony [Lewis-Jones] said that important decisions were being made in the office, not in the co-op. Kath Horseman said that a mood had developed and that there was a split in the co-op. Design of covers etc should be part of the ordinary members’ participation. Alanna [Farrell] said she felt the same. She did not like the love poetry anthology cover and would have liked the right to argue against it. Tony said that it should be possible to trust the co-ordinators to judge what were day-to-day decisions and what needed the decision of the whole co-op.’

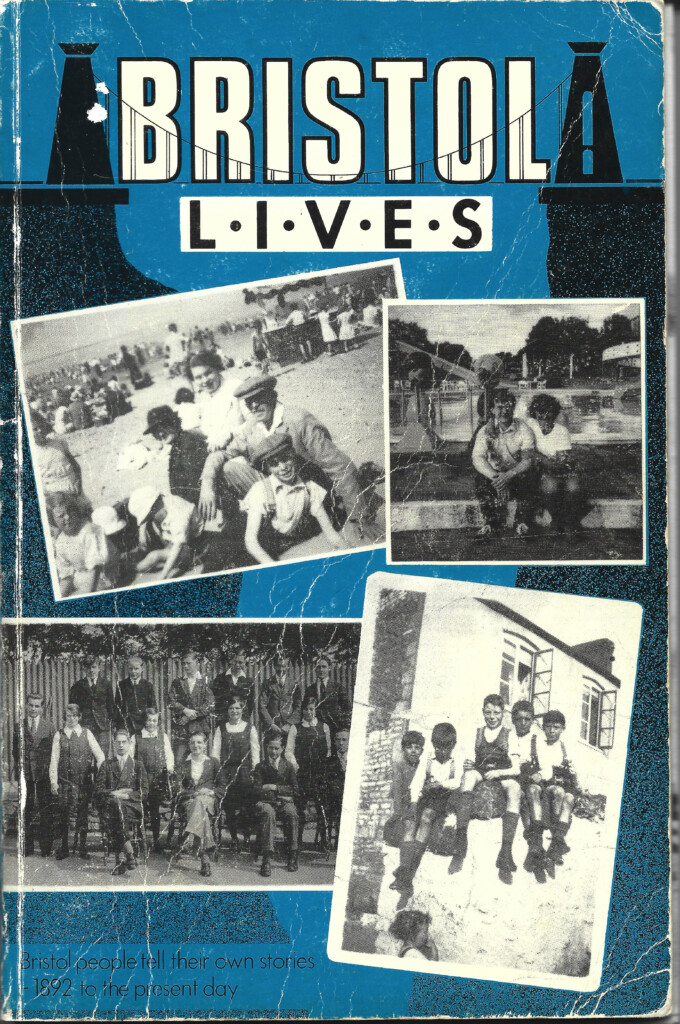

The two books in the Bristol Lives series were an extension of the early booklets that featured edited versions of the recorded conversations of older people talking about their lives. In the newer, bigger books, people from the workshops were writing about their lives, and these books were a big hit with readers. Phil explains: ‘The doorbell would ring and you’d let people in. And they’d seen something about Bristol Broadsides and they had a story to tell. Were we interested in publishing it? Generally what you would say is, “Yes, take this along to a workshop, you should share this stuff”. But not everybody wants to work in a group or expose their writing for that instant feedback. So the Bristol Lives books were partly a response to that.’

He continues: ‘The two Bristol Lives, I think those are the two things that I enjoyed most working on. As well as Joyce’s books. Because they drew together such a variety of different voices. Once the co-op had given the nod to getting that book going, it meant that when people came in we could say, “Why don’t you bring your work along to the workshop?” And if they went, “I’m not sure. I’m a bit uneasy about that. Can I not just come in and talk to you about it?” Then we could say, “Well, we have got this publication, so if you want to develop this and maybe submit it…” We got some really fantastic writing that just literally walked in off the street.’

There were two standouts from the series in Phil’s eyes: May Whitby and Ron Glade. ‘[May] just knocked us over with her writing. She came in and had some sheets of paper, and we sat there and read them. Quite an intense figure, not someone who was going to go to writers’ workshops. But just bringing in this treasure. While Ron writes about being a drag artist in the 1940s. Ron was a very nervous person who didn’t really want to go to workshops. He quite often turned up at the office and he wanted to chat and share things, and he just had an amazing story to tell about the 1940s drag scene. Talking about him being in full drag and getting caught up in a bombing raid, when it got so hot that his tights started to melt onto his legs.’

1988

Norma and Phil left Broadsides in April and their replacement was Laura Corballis, who had initially come to Bristol to work on her PhD in feminist history. What did her day-to-day job involve? ‘What didn’t it involve!? Making sure the groups ran effectively, collecting and editing material for publications, dealing with the funders. James [Hood] did all the paperwork. We got a lot of unsolicited manuscripts, and I wasted a lot of my first months trying to read them all and give people feedback until I realised that was just impossible for one person to do.’

Laura adds with pride: ‘There was never a publication from this, but I organised a day conference for women writers by myself. It was quite a feat to bring it off. We had it in the Folk House and somehow advertised it nationally. There were 50 or 60 women, and we did workshops through the day, and it was just really positive. And then we all went and listened to Michèle Roberts talk at the Watershed that night. So that was a happy end to a really exciting full day.’

1989 and 1990

Tensions had been simmering at Broadsides for a while but in 1990 they really began to boil over. In addition to grievances from some people about how the finances were handled, there was also disquiet about which people or groups had work published.

‘[Broadsides] had stopped publishing books purely because of a lot of internal disagreements,’ says Bertel, who was chair by this point. ‘The Bedminster group felt that they should be published more often because they’re actually writing and producing things. And other people were saying, “No, you’ve had more books published than any other group and it should be the time for some other groups to get published.” Because Ian Bild had left by then, and it was Laura Corballis and James Hood who were the coordinators, some of the people felt that the coordinators weren’t quite as working-class as the participants were.’ When asked if she thinks the fact she was middle-class was a factor in this argument, Laura says with certainty: ‘Oh god, yeah. Absolutely. Totally.’

Laura continues: ‘It was only possible to do one or two publications a year so there was some competition between the groups over that. And that developed into quite a lot of ill will between various groups. Basically that just developed into never ending conflict to the point where our funders withdrew money. Rightly so. We weren’t doing anything. We were just fighting. And I walked away from it.’

Bertel adds: ‘I think Bristol Broadsides might have been a victim of its own success, which sounds twisted. I think part of it was it had developed people who didn’t really see creative writing as an opportunity, more as an outlet, but they actually achieved a lot more than they thought they could and then wanted more. Suddenly you had people who were like, “We’ve done this, we’ve had success. I’ve got enough ideas that I can produce a book a year.” And Bristol Broadsides wasn’t catered for producing a book a year for people. I think that ended up building some of the frustration, because at that time you were still getting new people coming in who had not experienced any of that.’

‘Community publisher Bristol Broadsides is not to get any cash from Bristol City Council this year. The group – best known for its “Bristol Lives” book by local people – faced a management split last year. It has applied for £13,000 from its major funding organisation, South West Arts, but has been warned it may get nothing because of its problems.” (Bristol Evening Post, 16 March 1991.)

In a news report on 3 January 1990, the Bristol Evening Post wrote: ‘A Bristol charity has suffered a “serious breakdown” in management according to letters from its major backers, Avon Country Council and South West Arts … Broadsides chairman Bertel Martin is warned in a letter from Avon community arts officer Carol Bemant: “… You could be jeopardising the chances of receiving continued grant aid.” South West Arts literature officer Ingrid Squirrel wrote to Mr Martin: “We have severe misgivings about the way in which Bristol Broadsides has managed its affairs over the last few months.”’ The report went on to say Broadsides’ accountant had refused to sign off the accounts for the year ending 1989 and that some members were considering forming a breakaway group.

The way that Broadsides was structured made it easy for members to argue against decisions they didn’t like. So if a decision was passed in one meeting, it could be raised again in the next and potentially voted against, meaning that it was difficult to move forwards with anything. ‘It was hopeless because nobody ever accepted if a vote went against them, they just brought it up the following month, and sometimes the vote changed, or sometimes nothing happened because there were arguments about it,’ says Laura. ‘I felt completely out of my depth and very upset and it was unbelievably stressful.’

By October, Bertel had stood down as chair and Kathleen stepped up as acting chair. And by 23 October 1990, the Bristol Evening Post reported that a committee meeting decided that Laura must go in order to save her £6,000 salary; it was felt this would put Broadsides’ finances in a more stable position. Only a few days later, other members deemed that meeting to be ‘illegal’ as it had not been called officially and Laura had not even been at the meeting: ‘It cannot be a properly constituted committee unless all members are told about it,’ acting vice-chair Joe Solomon told the Bristol Evening Post on 25 October 1990. Laura now says: ‘It wasn’t a legal meeting. It wasn’t called in accordance with our rules and procedures. I think it was called specifically for me not to be there. We’d lost our funding, so we did have to save money. And I obliged. I came to my senses and got another job.’

In December 1990, South West Arts confirmed they would not be funding the organisation in 1991. Disgruntled Broadsides’ member Benjamin Price told the Bristol Evening Post: ‘Until three years ago it had been a very good group but it has become far too left wing. The power should go back to local people instead of the part-time workers that had been appointed.’

Also in December 1990, acting chair Kathleen said she was stepping down due to the ‘harassment’ she had endured since taking the voluntary post. Having been a Broadsides member for 15 years and a contributor to many anthologies, this was quite a statement.

There was one meeting where Ingrid Squirrel from South West Arts ended up storming out after Broadsides’ employee James Hood was attacked by one of the members. ‘James was assaulted,’ confirms Laura. ‘This was after I moved on so I didn’t witness it. One of the men just physically attacked him. That’s how bitter and angry it had got.’ Bertel adds that this matter ended up in court.

By August 1991, some members of Broadsides had launched a petition calling for an inquiry into how Broadsides had been funded. It is not thought this was ever pursued. But it was all a very sorry and unhappy end for a once-vibrant workers’ co-operative.

‘The real Bristol Broadsides is its groups and its members. It is the aims and values that cared about the ordinary people of Bristol – aims that people like me who helped start it believed in, that gave people confidence, gave the lonely a chance to meet others and, most significantly, the chance to be in print.

‘The office and its workers played such a small part. The workers were new in many ways to the history of Bristol Broadsides, and there were just one-and-a-half workers to deal with the paperwork, the eight groups, meetings, fundraising, three-year planning, proof-reading, the office, finance – and the conflict of commands that were all part of this fine organisation.

‘But, because of some people who see just the office and the workers and who have forgotten the compassion, the care, the aims and values that I so strongly believe in, I was made ill and, in protest, resigned. But some do care in their hands the work carries on – for I do not count, the work and the aims do, for the groups and the members are the REAL Bristol Broadsides. Pam Davies, Bedminster.’ Bristol Evening Post, letters page, 4 October 1990

Reflecting on Broadsides:

David Parker: ‘I’d describe it as a little publishing outfit doing something that was quite different from what the mainstream publishers were doing. A lot of these books are a collection of people writing together and supporting each other. So there’s a lot of collectivism and a lot of mutuality about it.’

Ted Fowler: ‘I think it made people’s sense of their lives more valued. I think the basic thing of recognising people’s creativity and empowering them is great. Some of the stuff, like the history ones from Madge and others, and Richard Gillings’ disability stuff, they made people in the mainstream notice important things.’

Ian Bild: ‘I think we were a bit amateurish in some ways, but people said, “Look, all this stuff that we’re doing now is because of the work that you did then.” I said, “Come on. There were other things that were happening.” But they said, “You were like precursors. You were breaking new ground then.” And that gave me great pleasure to hear that. The sense that the work that we thought then was important is seen now as being important to the work that’s continuing today.’

Bertel Martin: ‘I think it was that whole experience of Bristol Broadsides which makes me listen, makes me look out, makes me appreciate and value some of those smaller voices which suddenly bubble up and just catch your attention. Where I was before is completely different to where I am now. Definitely.’

Madge Dresser: ‘As a group we challenged the more complacent elitist approaches to history. It certainly wasn’t my contribution but I did feel that we offered a more inclusive view of the past. We helped change the way Bristol’s past was viewed. I think we offered a critique of what actually got into the public memory. It was Ian Bild, Dave Parker, Colin Thomas, Steve Humphries and Myna Trustram, and these are all people who were really bright and had something to say and made an impact.’

Phil Smith: ‘It was giving a platform to voices that generally were not being valued. It was fantastic having the books and there were some wonderful books, but it was just having that organisation that was working in that way. Anything that’s vaguely democratic is always going to creak and have rows but you can get round that. All the time alongside that is this very productive, creative stuff happening. So when that was meshing together, and all the bits could get on with the other bits, that was very inspiring.’