Bristol in 1973: Sex, Drugs and Rock ‘n’ Roll How we got from then to now...

Share this

Exploring the city of Bristol in 1973, historian and writer Eugene Byrne looks at Bristol and culture and the culture wars that year.

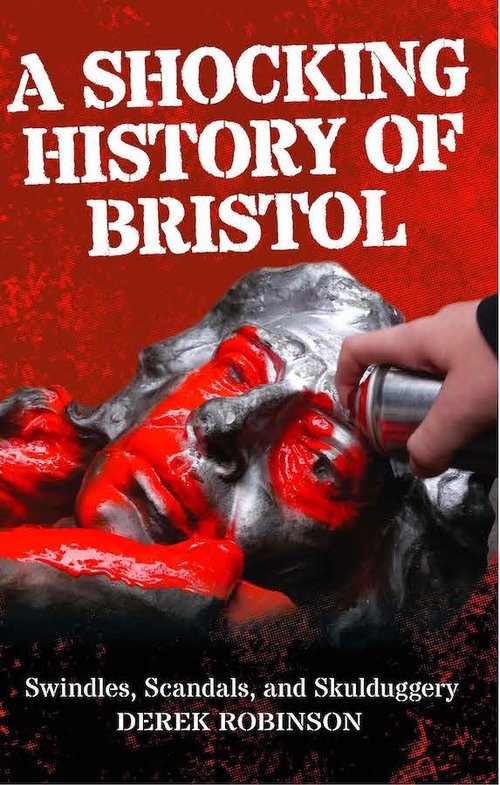

‘Mr Derek Robinson has had the gall to inflict on Bristol a book which our forefathers would have ordered to be burned by the common hangman,’ wrote an outraged Bristol Evening Post reader in August 1973. The offending book, he continued, was ‘a scandalous libel on our fair city … just a tissue of lies and insults from beginning to end. ‘After I had read this book I felt so mad I threw it on the bonfire and it gave off a reddish, sickly flame and smell.’

The physical differences between Bristol in 1973 and Bristol now are easy to spot. We have a lot of buildings now that weren’t around then. Much of the city docks area was overgrown and derelict, where today it’s all apartment blocks and cafés and bars. The fashions were different, nobody whizzed around on electric scooters and the cars were more boxy and less curvy than now. (The Austin Allegro would be launched in 1973, while the rather better VW Golf would come a year later.) That’s the physical differences done with. Ah, but the psychological ones, the values and attitudes – well, that’s where 1973 becomes a foreign country.

But we can see some stirrings of modern Bristol in Mr Derek Robinson’s book. It may have given off a whiff of brimstone when Outraged of Whitchurch flung it on the fire, but the slim little volume would go on to become the single most influential book about Bristol’s history to be published in the 20th century. (Other opinions are available.)

Originally titled A Shocking History of Bristol, it’s rarely been out of print in the last 50 years, though a later edition was called A Darker History of Bristol, and now it’s A Shocking History once more. Among other things it’s provided two generations with a brief introduction to Bristol’s part in the transatlantic trade in human beings.

Otherwise, you’d have plenty to complain about if you found yourself stranded in the city of 1973. Even if the time machine delivered you there with everything you’d need to get by, which might include a full wardrobe of period fashions, two Bs and an A at A Level, and ten grand in paper banknotes with pictures of the middle-aged Queen Elizabeth II on them.

The smell of smoke

Take smoking for instance. Over half the adult population of the UK smoked, but in Bristol it was probably a bit more. Tobacco employed 6,000 Bristolians at the time and many were entitled to free or cheap cigs. It would feel like everyone was smoking everywhere. Pubs, restaurants, cafés, cinemas, in the office or factory – the whole city stank of cigarette smoke. Go outdoors for some fresh air and you’d see billboards advertising various brands all over the place.

Some smokers were in denial, others admitted it was bad for them, several were trying to quit the habit, but Wills were nonetheless building a huge new £15m state-of-the-art manufacturing complex at Hartcliffe. John Wilson, Chairman and MD of W.D. & H.O. Wills explained in a 1973 interview with the Post that while there had been a sudden decline in smoking following the Royal College of Physicians’ report 11 years previously, “the drop in sales was not a lasting one.”

A growing population meant that there would always be new smokers to take the place of those who did not take it up again, he said. You could get 20 Benson & Hedges filter-tips for just 27p. Nowadays they’d set you back around £14, you have to ask specially for them while a disdainful shop assistant opens the poisons cupboard to get them, and they come in packets featuring pictures of rotting bodily organs. In 1973 cigarettes came in attractive, colourful branded boxes, many of them made by Bristol’s still-thriving packaging industry.

The culture wars of 1970s Bristol

Nowadays we talk about ‘culture wars’ over issues such as race, trans rights, sex work, Brexit and so on. Bristol had culture wars in the 1970s, too, but they were somewhat different. To compare culture wars between then and now, there’s a simple trick that works a lot (though not all) of the time: Just flip the political left and right.

So on 1 January 1973 the UK joined the European Economic Community (EEC). Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath, who as a younger man had seen at first hand the horrors of the Second World War, was determined to take Britain into Europe in the belief that friendship, co-operation and economic interdependence would make such a catastrophe impossible ever again.

For several decades it’s been Tory PMs who’ve had problems with Europhobic backbenchers, but in 1973 it was, aside from a few right-wing weirdoes (Enoch Powell), mostly Labour’s problem. Opposition leader Harold Wilson promised a referendum to pacify those of his MPs and trade union backers who regarded Europe with deep suspicion.

As with Europe, so it was with cancel culture. The people who nowadays want to ban and censor things generally like to see themselves as political progressives while those on the political right complain about the policing of their thoughts, words and choices in entertainment by woke puritans. In 1973 it was those on the right who generally wanted to ban things, usually because of offence to their values and ideas of what constituted decency. So, for instance, many white people who used the N-word freely would have been shocked at the use of the F-word, never mind the C-word.

Sex on screen

But when it came to 1970s cancel culture, sex in all its forms was the principal battleground. Last Tango in Paris, Bernardo Bertolucci’s film about a doomed sexual relationship between a middle-aged man (Marlon Brando) and a much younger woman (Maria Schneider), came out in 1973. It was in most senses a conventional European art movie of its time, but it also featured loads of sex and nudity, including a particularly notorious scene involving butter.

There were strident demands for Last Tango to be banned from Christians and family-values campaigners spearheaded by Mary Whitehouse. Councils in many towns across the country heeded the call and prohibited its screening in local cinemas, including several neighbouring towns to Bristol. Calls to ban it in Bristol were ignored and it opened at the Union Street Odeon on 8 June, with no reports of pickets or protests.

If there were demands for the film to be cancelled nowadays, objectors would cite the way that Schneider, 19 years old when Last Tango was made, later said she felt violated by the (simulated) anal rape scene and the way in which the film affected her mental health in subsequent years.

The permissive society had well and truly arrived – or that’s what people making money out of it wanted you to think. Newsagents stocked various men’s magazines, with photospreads of naked women in between the articles about fly-fishing, cars and other manly interests.

The dirty raincoat brigade, as cinema usherettes called them, definitely got their money’s worth with Last Tango at a time when many cinemas were showing sex films, often just European art movies with a little nudity and with a salacious English title slapped on. Various clubs and even pubs in Bristol offered their patrons strip-shows. One of the country’s earliest Ann Summers ‘Sex Supermarkets’ had opened on the edge of Broadmead (30 Bond Street) in 1971.

In March 1973 the Granary, one of the city’s best venues for up-and-coming musical acts, particularly of what the record shops used to classify as ‘heavy and progressive’, hosted a gig by The Ladybirds, a competent but otherwise unremarkable female four-piece band from Sweden. But everywhere they played, the punters crammed in because they performed topless.

Beauty pageants

While blatant nudity in the cinema was anathema to some, the ‘objectification’ of women’s bodies had few opponents. Beauty contests were a regular summer fixture at all manner of events and venues, from places like the Cadbury Country Club to the biggest one in the region, the annual Modern Venus contest, at Weston-super-Mare.

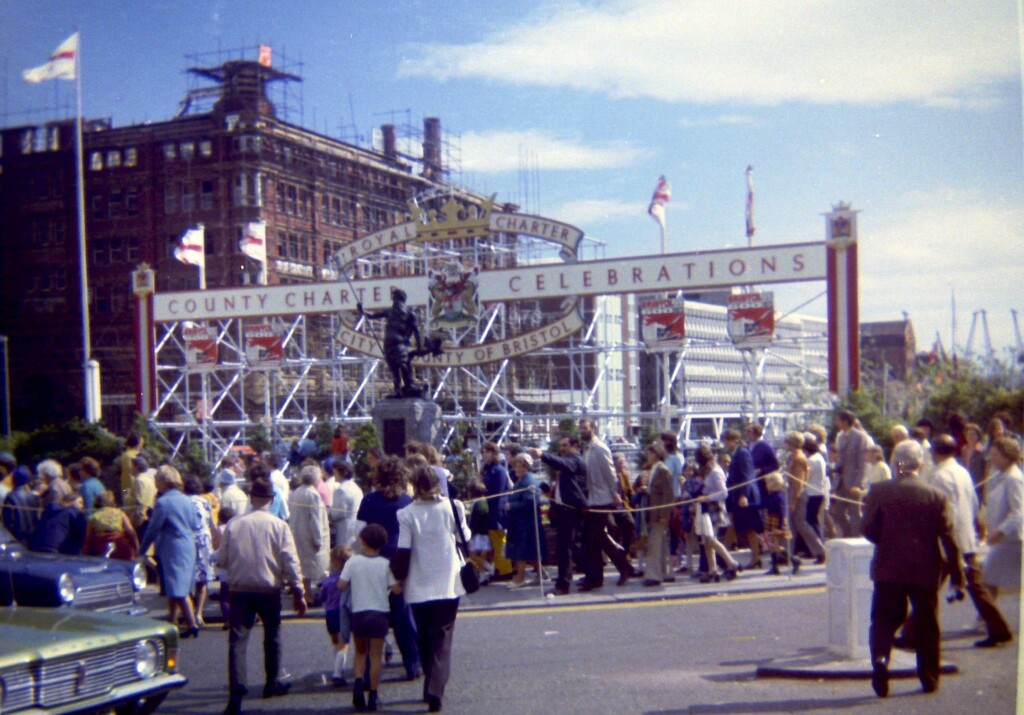

The biggest beauty pageant in Bristol in 1973, though, was to find Miss Bristol 600, who’d be an icon for the big celebration of the 600th anniversary of the charter by which Edward III had awarded county status to Bristol. The search for a ‘swimsuited dolly’, as the blurb for the HTV broadcast of the competition put it, came down to 12 finalists (including a schoolgirl of 16). The winner was 20-year-old Sally Lovell of St George, who won £600. The judges included the Lord Mayor, the Programme Controller of HTV West and the Deputy Editor of the Evening Post. There were also two celebrities on the panel, actors from two of the period’s most popular TV sitcoms. One can still be seen from time to time on various channels and streaming services. The other has virtually disappeared.

There was Doris Hare, who played the mother of Stan Butler (Reg Varney) in the On the Buses, all about the day-to-day adventures of a concupiscent young (Varney was actually 57 at the time) bus driver and his extended family. Then there was Nina Baden-Semper, one of the stars of Love Thy Neighbour, a sitcom made with the best of intentions, but long-since consigned to oblivion.

Nor would traditionalists argue with a somewhat different contest held in May 1973, when the swish new Dragonara Hotel hosted the 12 finalists in the Evening Post Bride of the Year contest. The women were put through their paces, spending the day competitively cooking and shopping because that’s what 1970s housewives did. In the evening they answered quickfire questions from celebrity MC Lance Percival, who also entertained the crowd with some of his impromptu calypsos. There was no hint of feminist protest, much less anyone condemning Percival’s ‘cultural appropriation’. The winner got £500. The runner-up got a gas cooker.

Gay clubs in Bristol

Moralists who were cool with beauty contests and housewifery competitions, were appalled by what they considered to be pornography, and many were aghast at the tidal wave of (male) homosexuality apparently sweeping the country. Decriminalisation in 1967 had not resulted in equality overnight, and there was still plenty of opposition to gays, some based on Biblical interpretations, and a lot more just rooted in prejudice and fear.

Bristol now had a few established gay meeting places. The best-known gay club in 1973 was the Moulin Rouge on Worrall Road, Clifton. As part of its licensing conditions the “Moulie” had to serve food; so there was a plate of wilting salad on display, though patrons were warned that it was not to be touched under any circumstances if they valued their health. One former Moulie regular later recalled being refused admission when he first tried to get in because he “didn’t look gay” and because he couldn’t name any other gay venues in the city. Sadly, these were legitimate security precautions at a time when “queer-bashers” stalked the streets.

Around the same time, the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, Britain’s leading gay lobby group at the time, had two branches in Bristol but had problems finding meeting places. In 1973 councillors in Weymouth argued bitterly over whether the campaign’s annual conference should be held at their resort. In Bristol a year or two later, the Folk House eventually agreed to host their events, though only after the board had a long meeting to argue over it.

Drugs

Drugs were now on the streets, too. Though not much. Bristol Constabulary (we didn’t get Avon & Somerset Police until 1974) had a drug squad which went around arresting people for possession of what were usually pathetically small quantities of cannabis resin. At this time, huge quantities of LSD were being manufactured in London and mid-Wales by a cottage industry later exposed by Operation Julie, but Bristol saw few arrests for possession of acid in 1973. Heroin and cocaine were almost unheard-of, but amphetamines did turn up in some quantity.

Rock ‘n’ roll

Rock ‘n’ roll? Yes, we had that, which was partly where the speed came in.

This was a golden age of live music, and a half-decent local band could make good money playing pubs, clubs and other venues. Plus, you might make it onto Top of the Pops one day, if only as one-hit wonders. But it was hard work, and many veterans of the ‘70s circuit will tell you only way they could play four or five gigs a week, and still turn up for the day-job the following morning, was to enlist pharmaceutical support. Few are nostalgic for purple hearts, dexies, bennies and black bombers, and few classes of drug are so contrary to Bristol’s present-day vibe.

If you wanted to see the big names of rock in Bristol, it was a fantastic year. Neil Young played the Hippodrome – supported by a relatively unknown band from Los Angeles called The Eagles. Over at the legendary Bamboo Club in St Pauls, they were bringing in acts from the Caribbean. Bob Marley (and the Wailers) played his second Bristol gig there in May. David Bowie in all his Ziggy Stardust pomp came to the Colston Hall, as did Genesis, Slade and Queen. Paul and Linda McCartney packed the Hippodrome with their new band, Wings.

Elton John’s career took off in ’73. He played the Colston Hall in March, but when he returned in November he was a huge star, mobbed by adoring young female fans. He was, said a local newspaper critic (who maybe knew something the teenyboppers did not), the biggest thing to hit a piano since Liberace. Like many Moulin Rouge patrons, Elton John figured that it was not a good idea to come all the way out of the closet just yet.

Back in the land of the conventional, the Bristol 600 celebrations, which centred on a huge show on the Downs that summer, got under way despite the atrocious weather.

A Shocking History of Bristol

It was the culmination of months of hype which got on Derek Robinson’s nerves so much that he took himself to the library, did some research, and within a few weeks produced A Shocking History of Bristol. ‘The book,’ he said years later, ‘was a corrective to all that excess when everyone was going around telling everybody what a wonderful city Bristol was. I grew up in Bristol, and I knew it’s as imperfect as any other city, and its history when I dug into it, proved the point.’

The slim paperback, price 50p, was simply a compendium of some of the more shameful and embarrassing episodes in Bristol’s past. It took in slave-trading in Anglo-Saxon times and the long slow decline of the port due to civic greed and dithering. There was the city’s ignominious record in the Civil War, the Queen Square riots of 1831, the Quaker-bashing mania of the mid-seventeenth century – and the triangular trade.

Robinson was no left-wing firebrand or academic intellectual. He was a middle-aged broadcaster, writer and rugby enthusiast. He would later be a successful Booker Prize-nominated novelist, but at the time was best known as ‘Dirk Robson’, the author of popular humorous books about the Bristol accent.

Perhaps his local fame helped, but A Shocking/Darker History has sold in quantities ever since it came out. Its ‘Six episodes of scandals, swindles, shambles, bungle, ferocity and farce’ were related in a brief punchy style which veered from taking the mickey to cold fury.

The chapter on transatlantic trade ran to just 17 pages, but it tells you everything you need to know about the trade in enslaved Africans – from a white European viewpoint, anyway. For decades to come, this was the most accessible and easily digested account of what it was that Colston and the others got up to.

You can still find a copy in many secondhand bookshops, or buy it new from tangentbooks.co.uk.

Stirrings of radicalism

If Robinson’s book was one of the first nudges in toppling Colston, there were few other stirrings of the radicalism some like to boast of nowadays. The St Pauls riot/uprising was still in the future, as were feminist campaigns against beauty contests.

The Green Party, which nowadays has a majority on Bristol City Council, did not exist; its forerunner, the Ecology Party, did not have a local branch until 1977. And even then, as one veteran Green likes to point out, Bristol had more fur shops than vegetarian restaurants.

Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll?

And so in conclusion – sex? Yes, there was loads of it; more than ever if pornography counts as ‘sex’. Drugs? Yes, some, but not as much as you might think. Unless you count nicotine, in which case Bristol probably had more drug-addicts in the ‘70s than at any other time in its history. Rock ‘n’ roll? Oh yeah. For rock ‘n’ roll in Bristol, 1973 was a truly great year.*

* Provided you ignore the fact that virtually all the big touring performers were male, and that the biggest all-female band to play Bristol were doing so with their tops off.

Top image credit: Peter Albanese via Unsplash