Bristol – Not So Swinging, Actually Eugene Byrne

Share this

Eugene Byrne is a Bristol-based author, historian and journalist. He has written several books on Bristol’s history, including The Bristol Story (with artist Simon Gurr) and a brief history of council housing in Bristol (with artist Anthony Forbes). He edits the Bristol Post’s ‘Bristol Times’ local history pull-out.

This article was written in advance of the screening of The Newcomers on Saturday 9 April 2022.

Given Bristol’s self-image nowadays – the radicalism, creativity, environmentalism, the woke progressiveness and, on sunny days, the low-lying smog of skunk – it would be reasonable to assume that Bristol in the 1960s was the San Francisco of Western Europe, right?

Well, no.

The images the decade summons in popular memory – the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, hippies, dope, free love and Carnaby Steet – are just that. Images.

Aside from a minority determined to live outside the mainstream, and another minority of glamorous and fashionable youngsters who had succeeded in showbiz, fashion or the media – or who simply had rich mummies and daddies – the Swinging Sixties were, for most people at the time, a vicarious experience mediated by TV, the cinema, newspapers and magazines.

The sounds and images of youth didn’t even dominate the singles charts. The UK’s biggest selling record of 1967 – you know, the year that youth was somehow going to revolutionise the world – was ‘Release Me’ by Engelbert Humperdinck. The biggest single the year before that was Tom Jones’ mawkish ballad, ‘Green Grass of Home’.

OK, so The Beatles’ ‘Hey Jude’ outsold every other UK single in 1968, but the only avant-garde thing about that song was the four minutes of ‘Naah naah nah nana na naah’-ing at the end.

Between 1959 and 1969, the everyday lives of most Bristolian adults didn’t change much beyond steadily improving and honestly earned prosperity.

Most travelled to work on foot, on bicycles and motorcycles and in green buses. The homes that half of them left each morning were owned by the council. They worked in offices and factories – many more factories than now – and most were paid weekly wages in cash. Going to work in a motor car was mostly for those whose pay went into a bank account each month.

Perhaps the availability of birth control pills changed some private lives, but until the end of the decade they were mainly for married women. In 1969 as in 1959 chaps were offered ‘something for the weekend’ at the barber’s. Madame Pierre’s shop on Silver Street was selling ‘rubber goods’ to mostly female customers well into the 1970s. Said goods included ‘Durex gloves.’ (These were not the sort of gloves you do the washing-up with. Please don’t ask me how I know this.)

The most visible change in Bristol over the decade, apart from a number of new and mostly horrible buildings, was that women’s skirts got shorter.

Most men’s hair was as short in 1969 as it had been ten years previously; long hair would have got a chap sacked from a lot of jobs and refused admission to everywhere except the barber’s.

To see what Bristol looked like, you’ll find old amateur and semi-professional film footage on Vimeo or YouTube, while a couple of feature films, such as The Beauty Jungle (1964) or Some People (1962), will show you parts of the old place in colour.

But to reach for the soul of day-to-day 1960s Bristol, you need the local papers. Back then, the Bristol Evening Post was selling over 100,000 copies daily. Even allowing for purchasers beyond the city boundaries, the paper was read in pretty much every household in Bristol.

The Post tells us what mainstream Bristol of all classes was worried or excited about, from the pronunciations of political and business grandees to the views of regular citizens in the letters pages.

Until the late ‘60s, the paper has little remotely countercultural to report, unless you count stories of a surprisingly large number of strange and mostly forgotten religious cults which pre-date any hippy weirdness by a long chalk. (Bristol’s longstanding taste for alternative philosophies and religions is a book all of its own.)

Recreational drugs are rarely mentioned. The odd bust for possession of ‘Indian Hemp’, as it was still called at the start of the decade, is your lot. (Though old-timers will nowadays tell you that amphetamine pills – the Mods’ drug of choice, often necked at gigs at the Corn Exchange – were the thing with Bristol’s In-Crowd.)

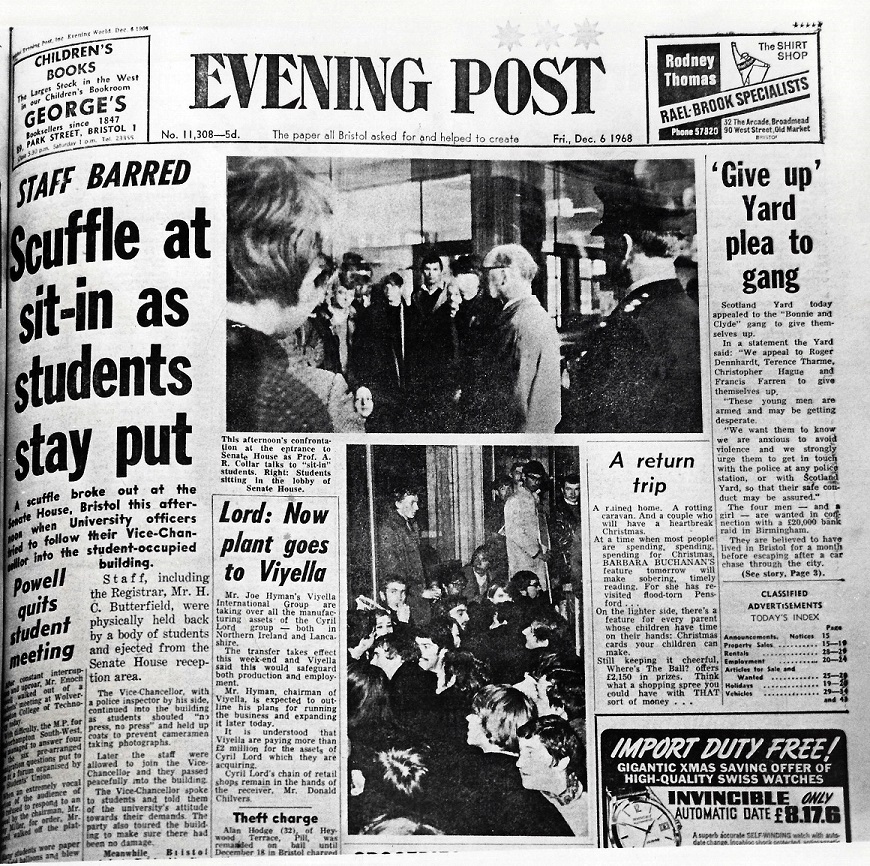

Student protest? OK, so in 1968, when the world was aflame with student agitation, Bristol Uni undergraduates did indeed stage their first ever occupation. The cause was laudable – equal access to the university library for local polytechnic and college scholars – but it wasn’t exactly the Paris événements, was it? The vanguard of the intelligentsia quit squatting the Senate House as Christmas and Mum’s cooking beckoned.

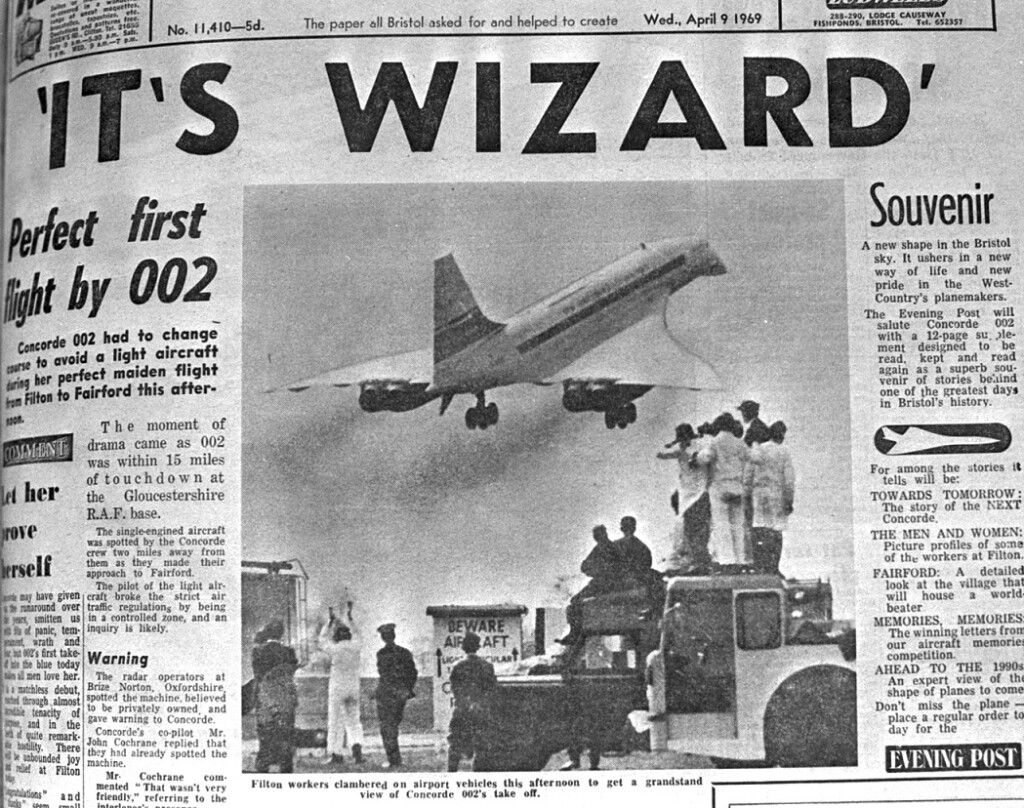

In the grown-up world of the Post, the headlines are all about the construction of aircraft at Filton, especially Concorde.

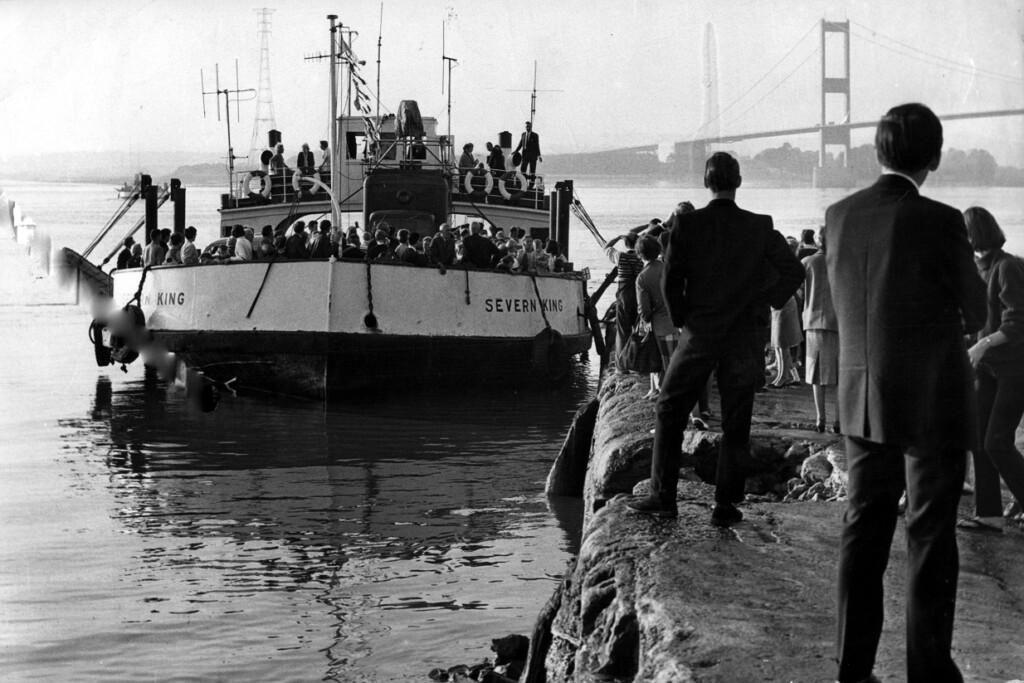

There was the coming of the motorways and the bridge over the Severn, the fortunes of City and Rovers and Gloucestershire CCC and a very large number of strikes and industrial disputes. Probably the biggest local political story of the decade would be Labour MP Tony Benn’s struggle to renounce his peerage to remain in the Commons.

By the end of the era, there were also growing rows about ring roads and the fate of the City Docks once they had closed, but this argument didn’t peak until the early 1970s.

There was the usual round of natural and unnatural disasters – the snows of ’63, the floods of ’68 – and endless tales of horrendous carnage on the local roads from the days before seatbelts, drink-driving laws, paramedics and safer car design.

For fun, there were more cinemas than now, but many were closing, or being turned into bingo halls. Bingo was becoming a hugely popular night out, especially for women.

There had always been restaurants, but thanks to the Berni brothers, dining out was no longer just for the wealthy. Berni Inns were the big Bristol business success of the decade, based partly on quality and pricing, but mostly on not being snobby or intimidating.

There was also a very 1960s entertainment phenomenon, now almost completely forgotten – the night club. Some were sleazy dives offering strippers and blue movies, but the best hosted the top entertainers of the day in cabaret. The biggest names came to places like the Arnos Court County (sic) Club in Brislington next to the TWW (later HTV) studios, or to the Webbington out near Axbridge.

(Comedian Frankie Howerd liked the Webbington neighbourhood so much he bought a house nearby and had a fall-out shelter dug in the garden for his antique collection. Because in the 1960s everyone lived with the constant, subliminal fear of nuclear war.)

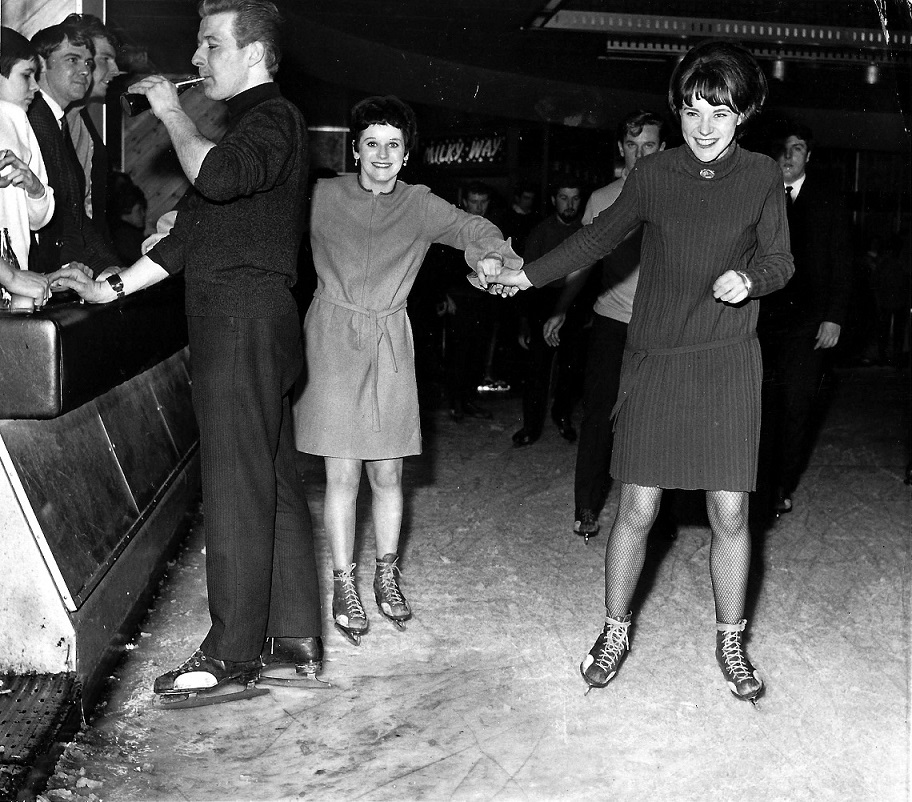

But Bristol’s biggest entertainment news of the decade was the opening of Mecca Leisure’s vast new complex, the New Bristol Centre, which would feature the Locarno ballroom/concert venue, a cinema, an ice rink and several themed bars.

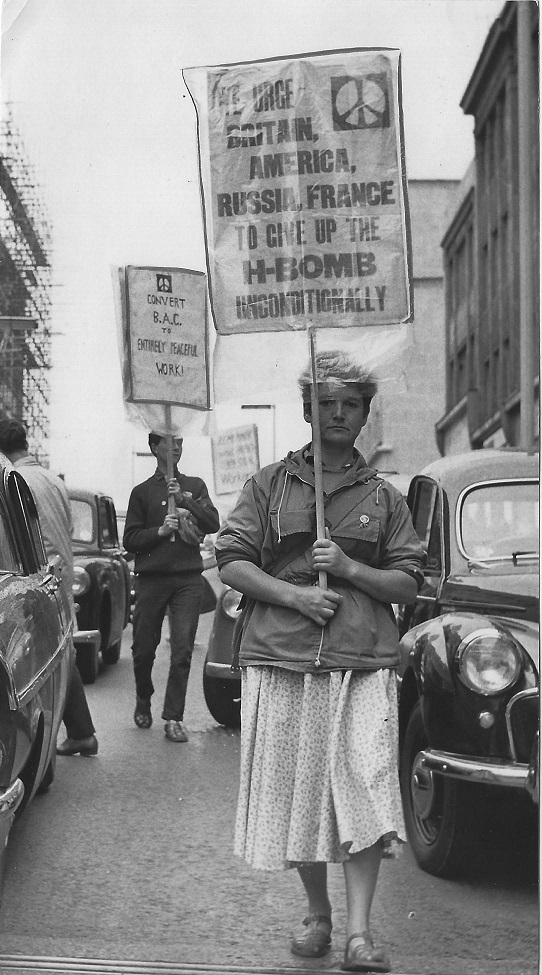

When the first shoots of hippydom appeared at the very end of the decade, they had not, of course, emerged fully formed from nowhere. There were antecedents; some in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament – which was huge in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s and many of whose members naturally progressed into protest against the Vietnam war. Other origins were in Bristol’s small but lively and influential folk music scene.

Much of the local counterculture came from Clifton, de-gentrified post-war, and now being colonised by young middle-class types attracted by low rents and houses with views and character.

There are a couple of excellent portraits of this particular place at this particular time. Stephen E Hunt’s Angela Carter’s ‘Provincial Bohemia’ (Bristol Radical History Group, 2020) is ostensibly an account of Carter’s formative years living in 1960s Clifton (and Bath in the early ‘70s), but it’s also a chatty and colourful evocation of a community of semi-conformists drawn to Clifton from all walks of life.

There’s also The Newcomers. John Boorman’s six-part documentary series is partly an intimate profile of young couple, Anthony and Alison Smith, both from relatively modest backgrounds and both beneficiaries of the welfare state and their own intelligence and educational achievements.

It does also take in vistas of the wider city, from dockers being hired for a day’s work through an exuberant evangelical service in St Pauls and then on to dancing the twist at the Glen, but it’s really about Clifton, about the Smiths and their friends.

These are high-minded, well-read 20/30-somethings. They are the spiritual, often literal, parents and grandparents of the present-day middle-class progressives who have shaped modern Brand Bristol.

They talk a lot about Dead White Male writers and composers in the same way their modern counterparts talk about film directors and computer games. They were not representative of all of Bristol then, any more than their descendants are now, but The Newcomers shows you how much of Bristol’s later countercultures took root.

But of course it was never just about ideas or ideology. It’s lifestyle and money, too. If you want to know where modern Clifton came from, watch the episode in which the Smiths are house-hunting. An estate agent explains that a nice place in Clifton will cost around six grand, while their friends are telling them how they’ve bought semi-derelict Georgian piles and are spending their evenings and weekends gentrifying.

Says one: ‘My good lady and I bought this place for £250. We just moved in and slept on a mattress, just slowly doing the place up, one room at a time.’

Yeah, but £250 was worth a lot more back then.

Yeah, sure it was. At the time that fellow and his ‘good lady’ were buying, the average weekly wage for a man in full-time work was probably about £25. So by that measure it’d be around £5,000 nowadays. And how long do you think even the wreck of a Georgian house in Clifton priced at £5k would be on the market for now? There probably isn’t an instrument sensitive enough to measure that small a fraction of a second.

Meanwhile, back in the mainstream media of mainstream Bristol, you do start to see newspaper photos of long-haired people wearing beads and kaftans by the late 1960s.

Trouble is, they’re all humorous entries in fancy dress contests and most are under the age of 12.

What most people think of as The Sixties didn’t arrive in Bristol until The Seventies. Same as in most other places. And it took a couple of decades after that for Bristol to become different.