And… Action! Friese-Greene’s First Movie Camera Peter Domankiewicz

Share this

Surely it was obvious? To make moving pictures, all you needed to do was record a series of images on a strip of film, which moved down through a camera, from one reel to another, stopping in front of the lens for each exposure. Easy peasy.

In fact, in 1887, just six years before the first commercially produced motion pictures would be shot by Edison’s team, none of that was clear at all.

For a start, people didn’t photograph on film, they used glass. Some stiff, transparent sheets of materials were being experimented with as a substitute, but were not widely accepted. William Friese-Greene had presented a camera in 1885 which could expose a series of such sheets rapidly, but was met with scepticism. In the first half of the 1880s, he had been based in Bath where he had encountered a local inventor, John Rudge, who was animating posed series of photographs on glass in various magic lantern inventions. Friese-Greene was involved with this, appearing in some sequences, and this was what had fired his passion to capture real life with photography.

In 1887, now in London, he presented a work-in-progress to the Photographic Society of Great Britain, showing a series of images – off glass, presumably – where “the result was an apparent continuous motion”. The following year he set to work on a larger project: a huge double lantern (projector), running by clockwork, with two chains of images in small glass frames, shown alternately. He even proposed that it could be synchronised with a phonograph to create a talking picture, but did not go that far. Despite it being on show at the 1889 Crystal Palace Photographic Exhibition, he freely acknowledged its shortcomings, telling the same photographic society that, “he intended to abolish the costly machinery before them as the same results could be obtained by simpler means.”

Some kind of simpler means were definitely in order. Across decades, various people had theorised about putting together rapid series of images on glass slides but, as Friese-Greene had discovered, it was very challenging. Eadweard Muybridge and Ottomar Anschütz had captured brief sequences of action using vast cameras involving multiple sets of lenses and photographic plates, but only Anschütz had reproduced them photographically – in a viewer which showed vivid loops of around two seconds. In 1888, Louis le Prince patented a system which involved sixteen lenses and two alternating rolls of paper film, but it’s unclear if he ever got this fully working. At this point, there was paper negative – which was just what it sounds like – and ‘stripping’ film, where you could, if you were adept, float the image off the paper after developing, but it was not something you could then roll up.

We can only guess what device Friese-Greene was using to record the images for that giant lantern, but it’s likely this was something that captured action in real time rather than took posed shots. By the June of 1889 we know that his ideas had moved on dramatically, because on the 21st of that month he proposed a patent for “Taking Photographs Automatically in a Rapid Series with a Single Camera and Lens.” Hopefully you can now see why the combination in that sentence constituted something notable.

His co-patentee, Mortimer Evans, was a successful Scottish civil engineer more accustomed to large-scale projects involving piers, railways, drainage and the like. Presumably they met via a scientific society they both belonged to – possibly the Royal Astronomical Society – and Evans contributed to the working out of the invention.

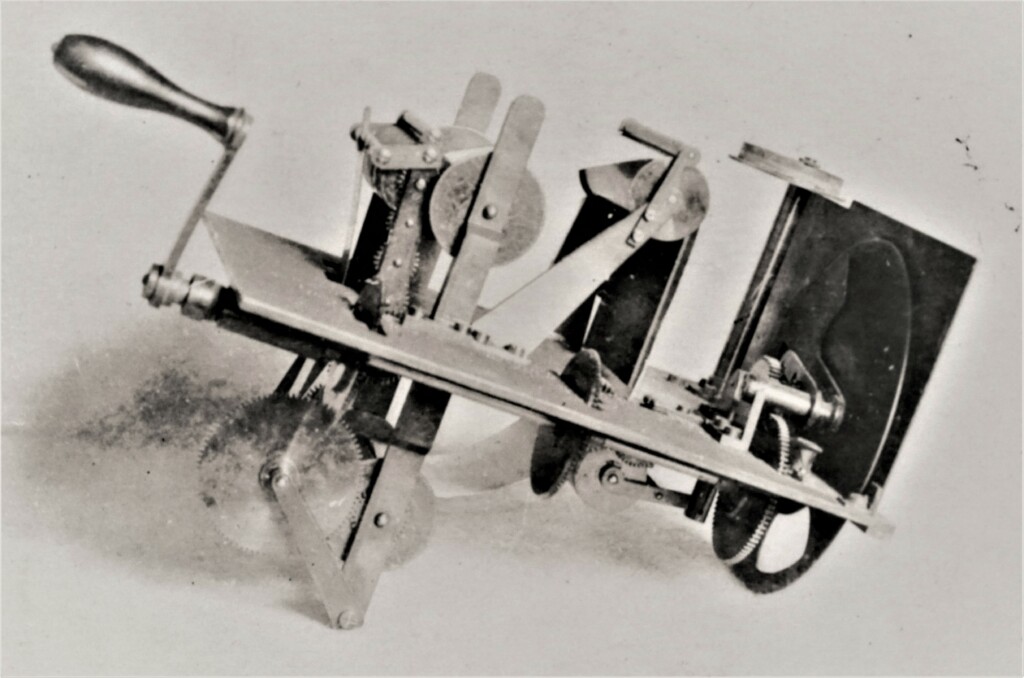

No sooner had the patenting process begun, than the company of Légé and Co in Hatton Garden. was set to work, building a motion picture camera for Friese-Greene that could shoot a series of images on a roll of film. Simultaneously, something else exciting was in the works on the other side of the Atlantic. Eastman (later to be Kodak) had just announced that they had succeeded in producing a new type of film, made of celluloid, “as thin, light and flexible as paper and as transparent as glass,” they claimed, “It requires no stripping, and is wound on spools…” They over-optimistically promised to bring it to market in a couple of weeks. In fact, it took several months. Nonetheless, samples of it reached Britain in November and Friese-Greene made sure he was one of the first to know about it, when an Eastman rep brought some to the Bath Photographic Society. At the start of the new year, it was on sale.

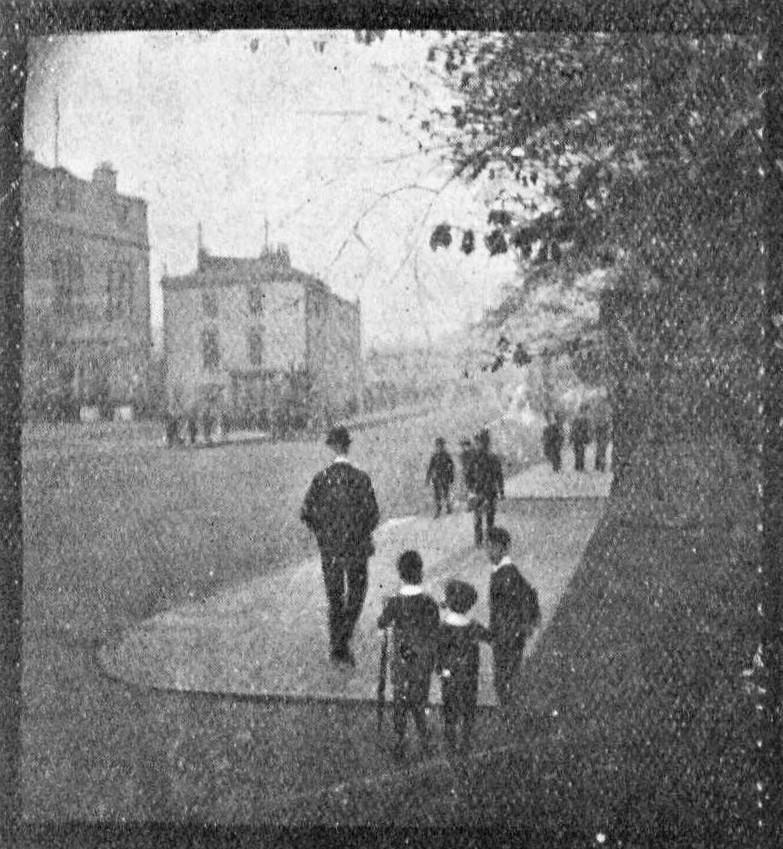

After assorted tweaks, Friese-Greene had taken receipt of his new camera on September 26th, 1889 and was keen to try it out. He later said that his first subject was the comings and goings around Hyde Park Corner, a film of some 20 feet in length – paper film, presumably. The picture format was 2½ inches square and, taking four pictures with every turn of the crank handle, the camera was theoretically capable of ten frames per second.

Friese-Greene’s excitement at the new possibilities this opened up burst out in a piece he wrote for the Yearbook of Photography, published that Christmas; “it is possible to show hereafter the ceaseless stream of life as it is today, and scenes of our own time can be handed down to posterity and show us just as we are with our dress of many fashions, even our gait, and the changing elements of the scene, all truthfully represented, not merely as a cycle of motion, as Muybridge ingeniously shows, but a continuous representation of street life from a given point… Not only that, but we shall be able to show a spider actually making his web and continuously photograph all the marvellous movements connected with its work. Also a cloud as it forms can be afterwards represented forming upon the screen or a flower or leaf opening and closing as it does in nature.”

He may not have foreseen the Marvel Cinematic Universe, but it’s fair to say this was a decent forecast of the medium’s potential.

Peter Domankiewicz is a film director, screenwriter and journalist with an abiding interest in the beginnings of moving pictures. He has written for the Guardian and Sight and Sound, as well as contributing to reference works and academic publications. He left his heart in Bristol and intends to pick it up.