Council Estate Memories: Acton, Stevenage and Basingstoke Joan Smith

Share this

My first home was a Georgian mansion standing in 200 acres of grounds, with stables, an orangery and a boating lake.

It was also a council flat, albeit a very unusual one: we lived on the first floor, overlooking a tree-lined drive, and our front door was flanked by a monumental arch that led onto a south-facing terrace. It was a lovely place to live, a world away from the grimy northern streets my parents had grown up in, but the most significant feature from their point of view was the indoor bathroom. At night, they no longer had to find a torch and tiptoe outside to an outdoor privy, and they even had piped water – no more carrying pails up the back stairs from a standpipe in the yard. Their address didn’t sound like social housing – the house was still known as ‘the large mansion’ – but that’s what it was, and my parents were incredibly grateful to have it.

Gunnersbury Park had once belonged to the Rothschilds but the family was long gone by the 1950s, and the estate in Acton was owned jointly by two West London councils. While Dad was still working as a gardener in his home town in the north-east, he heard that jobs in the park came with a council flat, something he was prepared to move 300 miles to acquire. Twelve months before I was born, my parents moved into an airy, two-bedroom flat above the old Victorian kitchens, where the only reminder of the house’s history was a door opening onto an internal staircase; in the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, the servants had used it to access the main section of the house when a member of the family rang a bell.

Dad had voted Labour in the 1945 general election and he was proud of the fact a working-class family was now enjoying the amenities, including the huge park, which were once the exclusive preserve of a wealthy family. He especially loved the walled garden where he worked in the old Victorian glasshouses, cultivating seedlings and learning more about his trade as a gardener. After work, determined to make up for the education he’d missed when he left school at 14, he had tea with me and my mother then rushed off to evening classes.

Both my parents came from South Shields, a windswept coastal town on the south side of the River Tyne. Like everyone else in their families, they had spent their entire lives in private-rented accommodation, often moving from one flat to another in the same street when the rent was increased or the landlord served an eviction notice. My mother’s family lived at several different addresses close to Tyne Dock, a heavily industrialised part of South Shields from which my grandfather used to sail on steamships transporting coal to London or Hamburg. A couple of times a year, we made the long journey by public transport from Gunnersbury Park to South Shields and I stared wide-eyed at the wash-house in my grandmother’s backyard, where she had taken in washing to support herself and four children after she was widowed. The toilet, with its old-fashioned cistern and long, dangling chain, was in an unlit wooden privy on the far side of the wash-house; a few years earlier, the night-soil man had made regular journeys along the cobbled lane behind Taylor Street, collecting human

waste with his horse and cart. I dreaded having to use it in the dark and I was even more nervous about staying with my mother’s elder sister, Auntie Doris, because her backyard contained a door, festooned with cobwebs, that led down into an Anderson shelter – an underground bomb shelter which was a relic of the Second World War. None of my relatives in the north-east had a garden and none of their landlords ever showed any interest in improving the properties they owned, not even in terms of providing basic amenities like indoor bathrooms.

Our council flat in West London was paradise by comparison. It was the first in a succession of council flats and houses that Dad was offered when he changed jobs, most of them in parks owned by the local authority.

When we moved to Slough, 15 or so miles west of Gunnersbury Park, our new home was the back half of a cricket pavilion which stood on its own in the middle of playing fields. After a couple of years we moved again, to a mill town in West Yorkshire, where Dad was offered a detached house on another private estate that had passed into the hands of a local authority. My aunts and uncles came to visit, admiring the modern kitchen and large garden while they remained stuck in cramped, soot-blackened Victorian terraces in the north-east. I knew we were the lucky ones in the family, entitled to social housing because of Dad’s job, but I didn’t realise that our accommodation was entirely untypical of the purpose-built council estates that were being constructed up and down the country.

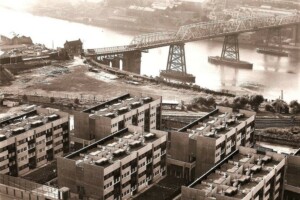

At some point in the 1960s, my maternal grandmother was offered a new one-bedroom flat in South Shields. It was clean, modern and had an indoor bathroom, but it was on an estate that displayed everything that was wrong about the social housing of the period. Constructed on a bleak tract of land on the outskirts of the town, it had few trees to brighten its appearance or shield the residents from the bitterly cold winds that blew from the North Sea. My grandmother’s flat had no garden, no outside space at all in fact, and it was a long bus ride from the shops in the town centre – not an easy or comfortable environment for an elderly woman who was losing her sight.

Around this time, Dad got a job as a parks superintendent in Stevenage, the first of half a dozen new towns planned by the Attlee government (under the New Towns Act 1946). Labour ministers had been sufficiently farsighted to see the post-war housing shortage as an opportunity as well as a crisis, allowing them to sweep away Victorian slum housing and replace them with modern homes. Thousands of Londoners were encouraged to move from the East End to what had until very recently been a village in Hertfordshire, a decision that caused uproar among existing residents. A Labour minister, Lewis Silkin, was shouted down when he arrived to outline the government’s plans at a public meeting in the existing village, but he brushed aside objections. ‘People from all over the world will come to Stevenage to see how we, here in this country, are building for the new way of life,’ he declared.

It was a utopian vision, conceived by ministers who would never have to live with the bland, featureless architecture that became characteristic of new towns. In Stevenage, the pedestrian-only shopping centre was a genuine innovation, opened by the Queen two years before we arrived, but it looked more like an illustration from a developer’s advertising brochure than a real place. The town was run by a development corporation, appointed by the government, which started out with good intentions, acknowledging that most people wanted to live in houses rather than the high-rises that were being built in existing towns where land was in short supply. But the result was half a dozen large council estates with an identical set of amenities: a row of shops, a community centre, a pub, a school and a church.

The planners seemed to think that once they had provided housing and shops, their job was all but done. The new town didn’t have anything resembling culture in any form: there was no theatre, no art gallery, not even a cinema to serve the thousands of ex-Londoners who’d been used to going ‘up West’ to catch a show at weekends. Franta Belsky, the Czech sculptor who was commissioned to provide a statue for the town centre, once remarked that ‘a housing estate does not only need newspaper kiosks and bus-stop shelters but something that gives it spirit’, an observation which went entirely unheeded by the development corporation. The old town, with its population of 6,000 people, did have a cinema but if you wanted a social life in the new town, the choice was between the pub or the church. In a signal of the benevolent paternalism that characterised the government’s approach to the new town, Stevenage had lots of churches, yet the one on the Bedwell estate where I lived was so poorly attended that it was eventually demolished. At the same time, any manifestation of individualism on the part of council tenants was rigorously suppressed, so much so that we weren’t even allowed to choose the colour of our front door. Ours was purple, just like all the others in our little cul-de-sac, and we were not allowed to change it even though my mother hated it.

The planners’ biggest mistake, however, was a failure to diversify the town’s housing stock. There was no attempt to create a mix of social and privately-owned housing, thereby entrenching the division that already existed between the old and new towns. I had no idea, until we moved to Stevenage, that living in social housing carried a stigma, but I was the only girl in my junior school class who got a place at the girls’ grammar school; the 11-plus had recently been abolished, leaving the head teacher to decide which secondary schools we would attend, but low expectations of children from council estates were already deep-rooted. Separated from my friends, I found myself in a class with girls who certainly didn’t live in social housing; they came from the old town or nearby villages, carried violin cases and talked about holidays with their parents in gites. The school’s academic record was excellent but the girls who thrived came from the old county, not the new town’s council estates.

No doubt the glaring class divide I experienced had something to do with the fact that Stevenage was an artificial construct, created with a focus on clean, modern housing to the detriment of everything else. Later new towns could have learned from its mistakes, recognising that segregating council tenants on drab estates encouraged snobbish attitudes. A few years later, however, when my parents moved to one of the later new towns, it became evident that the same errors were still being made. Basingstoke was originally a market town in Hampshire, bigger than Stevenage old town, with assembly rooms that had once been visited by Jane Austen. It should have been easier to integrate the new town with the existing infrastructure but the planners appeared to have set out to do precisely the opposite; a brutalist concrete shopping centre and multi-storey car park were built next to the old high street and market square, squatting beside it like a rebuke to anyone who valued more harmonious styles of architecture. In the depths of winter, we moved onto a council estate which was miles out of town and only half-completed; our new house had one welcome innovation, central heating, but it was constructed of cheap materials and the metal window frames constantly dripped condensation. There were as yet no shops on the estate and the bus service hadn’t started, so Dad had to give me lifts to the girls’ high school on the far side of the old town. Once again, girls from council estates seemed to be in a minority or kept quiet about where they lived; council house girls went to the other school, I was told, a secondary modern called The Shrubbery which was universally mocked as ‘the scrubbery’.

I couldn’t wait to finish my A levels and go to university, although I was met with barely concealed astonishment when I suggested taking Oxbridge entrance exams. Instead I went to Reading University to read Classics, surprising just about everybody except myself and the school’s deputy head, who had taught me Latin. Not long afterwards, my parents managed to exchange their house on the grim new estate for an older council house, closer to the town centre and built in traditional materials. They lived there for several years but their final home, in a village near Worcester, was a lovely between-the-wars house which had been built as accommodation for army officers but was now owned by the council. Dad was very happy there, rightly regarding the provision of decent, affordable homes as an essential part of the social contract between government and people.

After she was widowed, and despite having voted Labour all her life, my mother took advantage of Margaret Thatcher’s reforms and bought their council house, becoming a home-owner in her early 70s. I had mixed feelings, disapproving of the damage council house sales did to the public housing stock, but I knew it would give her the freedom to sell up and move back to South Shields when she became less mobile and needed the support of her family. Her decision to buy was the consequence of an inequality that’s always troubled me, grateful though I am to have grown up in social housing: to this day, friends who live in council flats and houses have fewer choices about where to live, and less power over their lives, than those of us who own our homes.

I know there is more consultation with tenants these days, at least in areas with enlightened local authorities, but some councils still infantilise their residents and don’t listen even to legitimate anxieties about safety. I can’t help thinking that when they designed and built social housing on the cheap, local authorities were reflecting and reinforcing snobbish attitudes towards people who couldn’t afford to buy their own house or flat. Even now, the stigma that attaches to council estates hasn’t gone away, if anything getting worse as the gap between rich and poor has widened. From personal experience, I think that one of the reasons is the way in which post-war governments, no matter how well-meaning, marooned working-class people on housing estates that actually exacerbated class divisions. Plumbing matters, but so do people’s self-esteem and aspirations.