Housing After the Second World War

The Second World War interrupted the extensive house building programme that had followed the 1919 Addison Act.

By 1945 it was estimated that around 750,000 new homes were required to meet demand in England and Wales alone, the result of the ongoing housing shortage as well as the loss of so many homes from bombing raids.

Among short-term solutions was the construction of prefabricated aluminium housing in kitform, estimated to have a life of around ten years. In February 1944 the Minister of Aircraft Production, Sir Stafford Cripps, brought together representatives of the leading aircraft manufacturers in the country to discuss how they could help solve the housing crisis, recognising the industry possessed the necessary skills, technology and materials. This work was overseen nationally by the Aircraft Industries Research Organisation on Housing (AIROH) jointly formed by the Ministry of Aircraft Production and the Ministry of Works. Founder members included Bristol Aeroplane Company (BAC).

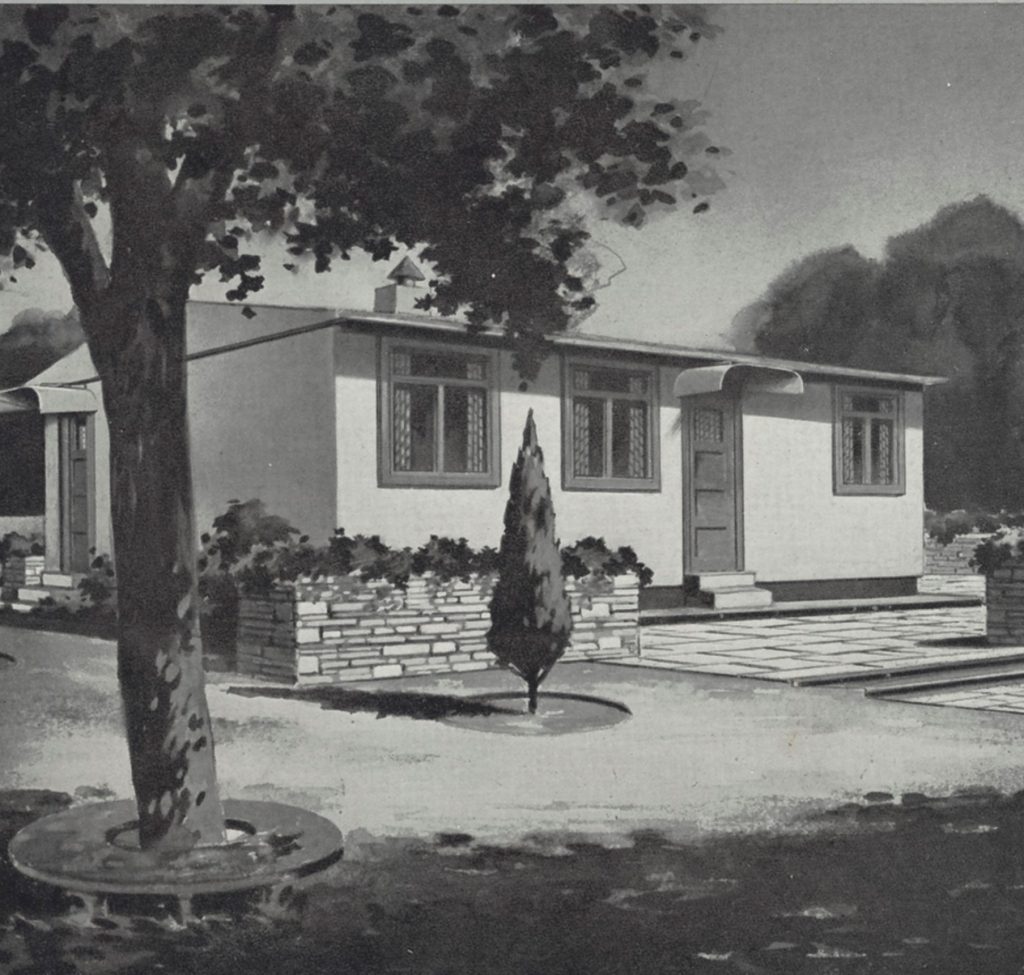

The photo at the top of this page is of a home being opened to view in Shirehampton, where the first tenant of a BAC-built bungalow moved in on 30 July 1945. The image below is taken from a BAC AIROH promotional brochure. (both images from Bristol Aero Collection). Other companies were involved in prefab construction both locally and nationally and it is estimated that a total of 156,622 went up between 1945 and 1949 across the UK.

Around 2,700 prefabs were built in Bristol. In 2004 it was announced that the surviving structures that were still occupied would be replaced by new council homes as part of a £35m scheme that was completed in 2014. Many residents were unhappy at the enforced move. (see Guardian article: Home is where the heart is, even when it’s a prefab and BBC News item: Last post-war prefab homes in Bristol are replaced).

In 1955 it was reported that 43 families per week were moving into new council homes in and around Bristol. Some of the shortcomings of the estates built in the inter-war period were repeated in those built at Hartcliffe, Henbury, Lawrence Weston, Lockleaze, Stockwood and Withywood after the war. They too had limited local amenities and public transport. They also suffered from the abandonment of the garden suburb principles, which had been a redeeming feature of the earlier developments, and other cost-cutting measures. The increasing use of pre-cast reinforced concrete construction resulted in major structural problems (concrete cancer) that would begin to come to light in the 1980s and eventually lead to the demolition of hundreds of council homes across the city.

Nationally high-density and high-rise became the norm for council-home building in the run-down inner-cities with low-cost, low-rise built on isolated suburban sites. Both forms of layout and location were beginning to be criticised by the early 1970s for their poor quality and negative social impact. Council housing increasingly became associated with people most in need (the rent levels of the first estates had been aimed at the more affluent members of the working-class rather than the very poor). Some estates started to be stereotyped by the media and those in authority as problem areas, high in crime and welfare dependency, thereby stigmatising residents. It should always be remembered, however, that the majority of residents enjoyed living in these homes just as previous generations had made a good life and built a positive sense of community in what were once routinely condemned as slums (something we will explore further through the Homes for Heroes 100 programme).

Councils increasingly focused on repairing ageing housing stock rather than building new. The Right to Buy policy introduced with the 1980 Housing Act meant councils were forced to sell off properties at the same time as the building of new homes was being cut back, thereby drastically reducing availability.

By the first decade of the twenty-first century many local authorities were faced with major housing debt and with restrictions on investment, bringing a complete halt to new building. Funding was available from government for improvement and regeneration, but this was often conditional on transferring ownership and/or management to non-public housing associations or Registered Social Landlords. Transference had been facilitated by the Housing Acts of 1985 and 1988. This was accompanied by a shift to the use of the term to ‘social housing’ rather than ‘council housing’. By 2010 around 55 percent of the UK’s social housing stock was still owned by local authorities, though of this only 15 percent was managed by local authorities on a day-to-day basis.

HomeChoice Bristol is a partnership between Bristol City Council and local housing associations that is used to allocate properties in the city. People who are applying to be added to the Bristol Housing Register on the council website are told from the outset that it is highly unlikely that they will be offered a council property because the waiting list is so long. Even people with the greatest need often wait several years for a council home. Fewer than 2,000 social housing properties become available annually in the city and over 8,500 households are currently registered.

In an interview in 2018, Paul Smith, Bristol City Council’s cabinet lead for housing said:

‘Council housing is part of the solution to the current problem, but not the only one. We need a mixture of different types of housing available to people, and that is what we are trying to do and will become a focus of the new housing company we are setting up. But it is also important to say that we wouldn’t use the same principles as previous administrations. We aren’t looking to build large estates, the focus is on integrated developments where social housing, affordable housing and market rate housing are all mixed on one site.’

At that time the council was on target to build 800 affordable homes (out of a total build of 2,000) by 2020.

Council housing had become a safety net for the most vulnerable in society but more recently there are signs that it is becoming a tenancy of choice again, rather than a tenancy of last resort. With the renewed building programme in the city, Homes for Heroes 100 will help to raise awareness of the mistakes of the past that should not be repeated – including problems of social alienation, lack of essential facilities and limited availability – as well as the many positive outcomes that should be publicly recognised.

Sources of background information

The History of Council Housing available on the University of the West of England website and dating from 2008.

Mike Manson’s unpublished paper: ‘Houses, Flats and Pre-Fabs: Bristol Council Housing’

Municipal Dreams, a blog by John Boughton to accompany his book Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Social Housing (2018)

Public Housing in the United Kingdom on Wikipedia

Dave Hall at the Bristol Aero Collection produced instructions for a make-your-own model AIROH pre-fab which you can download here: Prefab PDF. Our thanks to Dave for his permission to use this in Homes for Heroes 100. See also Dave’s website Flyers.org.uk.