Bristol Council Estates 1919-1939

On 23 November 1918 Prime Minister David Lloyd George delivered a speech in which he called for ‘a country fit for heroes to live in’ (frequently misquoted as ‘homes fit for heroes’).

During the First World War the Tudor Walters Committee had been established with the aim of improving the country’s housing provision by setting higher standards of design and location. This had been prompted by the realisation that many recruits had health problems that were the result of inadequate living conditions at home. Housing became a major responsibility for government in the post-war period as the private sector was unable to meet demand.

The 1919 Housing and Town Planning Act (often referred to as The Addison Scheme after the then Minister of Health and Housing Christopher Addison) helped trigger the council-house building programme nationally and the development of the first large-scale council estates. Although widely accepted as a passionate vision that would make a positive difference in the lives of citizens, it could also be argued that this was at least partly driven by political necessity to smooth the transition to peace.

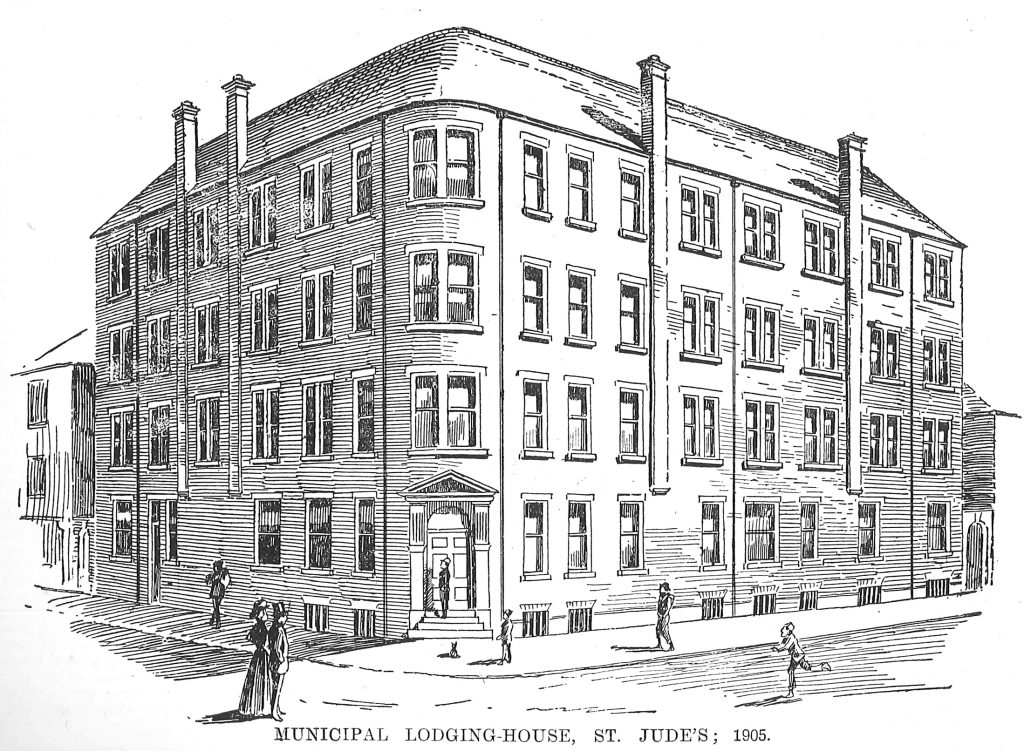

With the passing of the Act councils across the country began to establish housing committees, guided by recommendations from central government. Before 1919 local authorities had supported a range of rentable housing opportunities for those on low incomes unable to afford private-sector rents or to buy a home of their own. In Bristol, for example, an early example of council housing was a municipal hostel built in 1905 in Wade Street off Old Market in St Jude’s (pictured above, Bristol Archives/ Know Your Place). Other small-scale developments included tenement homes built in Easton, St Werburghs and St Philips (properties in the West Block of Mina Road, which were completed by 1906, survive to this day). A pre-war proposal for a 400-home estate in Bedminster was defeated in a council vote.

However, nothing had previously matched the scale of ambition heralded by the new act. It is from this point in time that the term ‘council housing’ became widely recognised. These were homes where costs were shared between tenants, local rate payers and the Treasury.

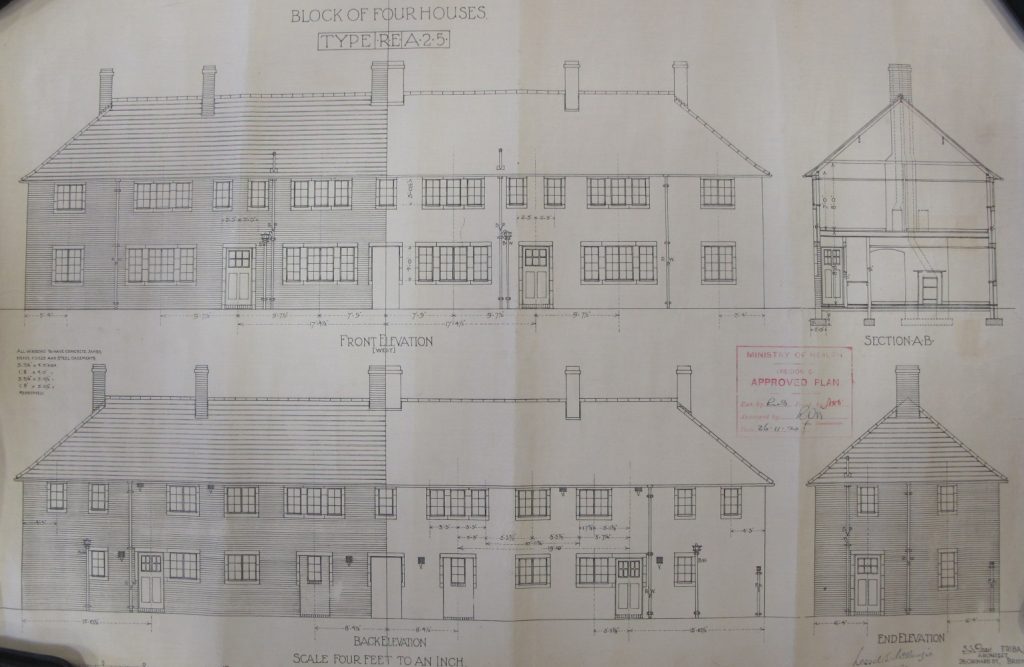

The city’s first council estate homes to be completed were located on Beechen Drive, Hillfields in 1919 (there is a commemorative plaque) and the first to be occupied were on the corner of Thicket Avenue and Briar Way (1920). In September 1920 over 87 per cent of the 676 applicants for houses on the Hillfields estate were from ex-service personnel. Many homes on the estate were designed with a parlour that could serve as a second living room or provide ground-floor accommodation for an injured former serviceman, unable to manage stairs. On 5 June 1920 500 delegates, drawn from across the UK, the British Dominions (Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand), Europe and the USA came to Hillfields to see a range of housing designs that had been constructed in what was termed the Demonstration Area (see below, a design by S S Reay for a block of four three-bed homes, two with parlours, two without, from the Demonstration Area Bristol Archives/ Know Your Place ref REA25 Red Label Plans 22/3/21). Local Learning is running the Hillfields Homes for Heroes project in 2019/21.

Other estates that were largely completed in the 1920s included Knowle, Shirehampton and Sea Mills. The first sod at Sea Mills was cut by Addison himself in a ceremony that took place on 4 June 1919: an oak tree was planted in Sea Mills Square to mark the occasion and remains today (see the website Sea Mills 100 for news of activity celebrating the centenary of the oak and the estate). In 1937 John Betjeman referred to Sea Mills as ‘that magic estate’ and in 1981 it became one of the first council estates in the country to be designated a conservation area (this was extended in 2008).

Supply still fell short of demand.

‘The house famine must be relieved, and it can only be relieved by the building in the immediate future of several thousands of dwellings. Thus a very serious situation has to be faced, and faced without delay.

‘Just pause for a moment and try to think of your own Home and then try and imagine what this shortage of houses means to the thousands of unfortunate people – men and women, youths and young women, and little children herded together, two, three, or even four families in one house, boys and girls occupying the same bedrooms, common decency, to say nothing of privacy, quite impossible. Try and imagine the babies born every day under these conditions, and the mothers at childbirth and after. Think of sickness and death when the whole family inhabit one or two rooms. Think of these and the grave possibilities to all citizens of Bristol inherent in the housing shortage will be clear to you.’

(from Bristol House Famine Campaign, 1923 (Bristol Reference Library, B21855). It was calculated that there was a shortage of 7,270 dwellings in the city at this time.)

Between 1919 and 1939 15,000 new council homes were built on estates that now included Bedminster, Horfield, St Anne’s Park, St George and Southmead. Over the same period almost 20,000 homes were built privately. The estates’ main disadvantages were that they lacked enough shops and services to meet the needs of residents for at least the first few years of occupancy and they were inconvenient for those still employed in the city centre and dependent on public transport.

The 1924 Housing Act (named the Wheatley Act after Labour’s John Wheatley) secured a further 15 years of building programmes. Subsidies to local authorities were raised to £9 per house per year having been previously set at £6 by the 1923 Housing Act introduced by Neville Chamberlain. To reduce costs and enable rents to be lowered, the size of council homes had already begun to shrink and estates increased in density. Generally quality remained good, though council housing was increasingly associated with the very poor rather than the more affluent members of the working class for which it was originally planned.

The Housing Act of 1930 extended the post-war slum clearance and relocation programmes. Many residents of the new estates would have previously lived in homes deemed unfit for human habitation.

‘Considering the conditions under which they had lived, with insufficient accommodation and lack of proper facilities for cooking, washing drying and other domestic duties, without gardens to afford relaxation or to stimulate interest in pursuits other than ordinary daily toil, it is generally regarded as highly satisfactory that the response of tenants to improved conditions has been so marked. They take a real pride in their new homes and gardens are well cultivated.’

(from The Housing Needs of Bristol in Relation to the Greenwood Act, February 1931 p25 (Bristol Reference Library, B22170))

The residents gained a superior quality of home at an affordable level of rent, but the clearance programmes meant they also often lost contact with a strong, settled community that had grown up over several generations. The continuing housing shortage would come to be exacerbated by the outbreak of the Second World War.

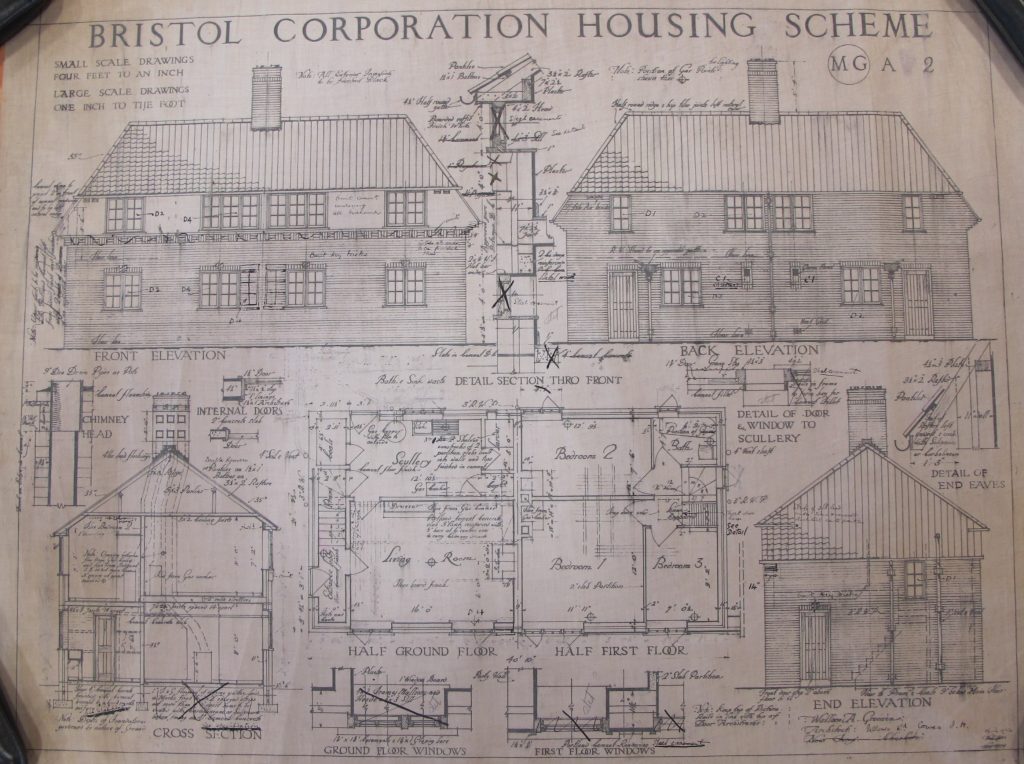

Design by Maidman and Greenen for homes built at Hillfields and Knowle Park in the early 1920s Bristol Archives/ Know Your Place (ref MGA2).

Sources of background information

Eugene Byrne’s chapter ‘“Homes Fit for Heroes” – Bristol’s New Housing Estates’ in Bristol and the First World War, published by BCDP in 2014. Available as a downloadable PDF

Homes for Heroes created by Myers-Insole Local Learning for the English Heritage Schools initiative in 2014. Available as a downloadable PDF.

The History of Council Housing available on the University of the West of England website and dating from 2008.

Mike Manson’s unpublished paper: ‘Houses, Flats and Pre-Fabs: Bristol Council Housing’

Municipal Dreams, a blog by John Boughton to accompany his book Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Social Housing (2018)

Public Housing in the United Kingdom on Wikipedia

Sea Mills: Character Appraisal and Management Proposals Bristol City Council January 2011