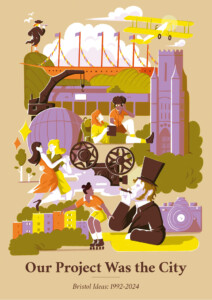

Bristol Ideas closed 30 April 2024. We are proud of the work we have done in Bristol. We thank everyone involved for their support, partnership and ideas.

Our Festival of Economics continues with the Economics Observatory at University of Bristol. Festival of the Future City has become Festival of Flourishing Regions led by Futures West with the Growing Together Alliance. An archive of our work is at Bristol Archives.

This site will remain as a legacy project telling the story of our work and the many events we have run. It includes interviews, articles, reviews, videos, audio recordings and books. You can read more about our history below.

Our newsletter will continue with details of legacy projects and events about ideas. To sign up for the newsletter visit the links above for Festival of Economics and Festival of Flourishing Regions.